ALONE IN THE CARIBBEAN

by Frederic Fenger

Item -- I order that my executors purchase a large stone, the best that they can find, and place it upon my grave, and that they write round the edge of it these words : -- "Here lies the honorable Chevalier Diego Mendez, who rendered great services to the royal crown of Spain, in the discovery and conquest of the Indies, in company with the discoverer of them, the Admiral Don Christopher Columbus, of glorious memory, and afterwards rendered other great services by himself, with his own ships, and at his own cost. He died. . . . He asks of your charity a Paternoster and an Ave Maria."Item -- In the middle of the said stone let there be the representation of a canoe, which is a hollowed tree, such as the Indians use for navigation ; for in such a vessel did I cross three hundred leagues of sea ; and let them engrave above it this word : "CANOA."

From the will of Diego Mendez,

drawn up June 19th, 1536.

CHAPTER I

THE "YAKABOO" IS BORN AND THE CRUISE BEGINS

"Crab pas mache, il pas gras ; il mache trop, et il tombe dans chodier.""If a crab don't walk, he don't get fat ;

If he walk too much, he gets in a pot."-- From the Creole.

IS IT in the nature of all of us, or is it just my own peculiar make-up which brings, when the wind blows, that queer feeling, mingled longing and dread? A thousand invisible fingers seem to be pulling me, trying to draw me away from the four walls where I have every comfort, into the open where I shall have to use my wits and my strength to fool the sea in its treacherous moods, to take advantage of fair winds and to fight when I am fairly caught -- for a man is a fool to think he can conquer nature. It had been a long time since I had felt the weatherglow on my face, a feeling akin to the numb forehead in the first touch of inebriety. The lure was coming back to me. It was the lure of islands and my thoughts had gone back to a certain room in school where as a boy I used to muse over a huge relief map of the bottom of the North Atlantic. No doubt my time had been better spent on the recitation that was going on.

One learns little of the geography of the earth from a school book. I found no mention of the vast Atlantic shelf, that extended for hundreds of miles to seaward of Hatteras, where the sperm whale comes to feed in the spring and summer and where, even while I was sitting there looking at that plaster cast, terrific gales might be screaming through the rigging of New Bedford whalers, hove-to and wallowing -- laden with fresh water or grease according to the luck or the skill of the skipper. Nor was there scarcely any mention of the Lesser Antilles, a chain of volcanic peaks strung out like the notched back of a dinosaur, from the corner of South America to the greater islands that were still Spanish. Yet it was on these peaks that my thoughts clung like dead grass on the teeth of a rake and would not become disengaged.

Now, instead of looking at the relief map, I was poring over a chart of those same islands and reading off their names from Grenada to tiny Saba. At my elbow was a New Bedford whaler who had cruised over that Atlantic shelf at the very time I was contemplating it as a boy. And many years before that he had been shipwrecked far below, on the coast of Brazil. The crew had shipped home from the nearest port, but the love of adventure was strong upon the captain, his father,* who decided to build a boat from the wreckage of his vessel and sail in it with his wife and two sons to New York. With mahogany planks sawed by the natives they constructed a large sea canoe. For fastenings they used copper nails drawn from the wreck of their ship's yawl, headed over burrs made from the copper pennies of Brazil. Canvas, gear, clothes, and food they had in plenty and on the thirteenth of May in 1888, it being a fine day, they put to sea. The son traced their course with his finger as they had sailed northward in the strong trade winds and passed under the lee of the Lesser Antilles. Later as a whaler, he had come to know the islands more intimately. "Here !" said he, pointing to the Grenadines, "you will find the niggers chasing humpback whales." On Saint Vincent I should find the Carib living in his own way at Sandy Bay. Another island had known Josephine, the wife of Napoleon, and another had given us our own Alexander Hamilton. And there were many more things which I should come to know when I my self should cruise along the Lesser Antilles. We talked it over. After the manner of the Carib, I would sail from island to island alone in a canoe. Next to the joy of making a cruise is that of the planning and still greater to me was the joy of creating the Yakaboo which should carry me. I should explain that this is an expression use by Ellice Islanders** when they throw something overboard and it means "Good-bye."

"Good-bye to civilization for a while," I thought, but later there were times when I feared the name might have a more sinister meaning.

* Captain Joshua Slocum, who sailed around

the world alone in the sloop Spray.

** In the Pacific Ocean just north of the Fiji group.

So my craft was named before I put her down on paper. She must be large enough to hold me and my outfit and yet light enough so that alone I could drag her up any uninhabited beach where I might land. Most important of all, she must be seaworthy in the real sense of the word, for between the islands I should be at sea with no lee for fifteen hundred miles. I got all this in a length of seventeen feet and a width of thirty-nine inches. From a plan of two dimensions on paper she grew to a form of three dimensions in a little shop in Boothbay and later, as you shall hear, exhibited a fourth dimension as she gyrated in the seas off Kick 'em Jinny. The finished hull weighed less than her skipper -- one hundred and forty-seven pounds.

From a study of the pilot chart, I found that a prevailing northeast trade wind blows for nine months in the year throughout the Lesser Antilles. According to the "square rigger," this trade blows "fresh," which means half a gale to the harbor-hunting yachtsman. Instead of sailing down the wind from the north, I decided to avoid the anxiety of following seas and to beat into the wind from the lowest island which is Grenada, just north of Trinidad.

My first plan was to ship on a whaler bound on a long voyage. From Barbados, where she would touch to pick up crew, I would sail the ninety miles to leeward to Grenada. A wise Providence saw to it that there was no whaler bound on a long voyage for months. I did find a British trading steamer bound out of New York for Grenada. She had no passenger license, but it was my only chance, and I signed on as A.B.

We left New York on one of those brilliant days of January when the keen northwest wind has swept the haze from the atmosphere leaving the air clear as crystal. It was cold but I stood with a bravado air on the grating over the engine room hatch from which the warm air from the boilers rose through my clothes. Below me on the dock and fast receding beyond yelling distance stood a friend who had come to bid me goodbye. By his side was a large leather bag containing the heavy winter clothing I had sloughed only a few minutes before. The warmth of my body would still be in them, I thought, as the warmth clings to a hearth of a winter's evening for a time after the fire has gone out. In a day we should be in the Gulf Stream and then for half a year I should wear just enough to protect me from the sun. Suddenly the tremble of the steamer told me of an engine turning up more revolutions and of a churning propeller. The dock was no longer receding, we were leaving it behind. The mad scramble of the last days in New York ; the hasty breakfast of that morning ; the antique musty-smelling cab with its pitifully ambling horse, uncurried and furry in the frosty air, driven by a whisky-smelling jehu ; the catching of the ferry by a narrow margin, were of a past left far behind. Far out in the channel, that last tentacle of civilization, the pilot, bade us "good luck" and then he also became of the Past. The Present was the vibrating tramp beneath my feet and the Future lay on our course to the South.

On the top of the cargo in the forehold was the crated hull of the Yakaboo, the pretty little "mahogany coffin," as they named her, that was going to carry me through five hundred miles of the most delightful deep sea sailing one can imagine. I did not know that the Pilot Book makes little mention of the "tricks of the trades" as they strike the Caribbean, and that instead of climbing up and sliding down the backs of Atlantic rollers with an occasional smother of foam on top to match the fleecy summer clouds, I would be pounded and battered in short channel seas and that for only thirty of the five hundred miles would my decks be clear of water. It is the bliss of ignorance that tempts the fool, but it is he who sees the wonders of the earth.

The next day we entered the Gulf Stream where we were chased by a Northeaster which lifted the short trader along with a wondrous corkscrew motion that troubled no one but the real passengers -- a load of Missouri mules doomed to end their lives hauling pitch in Trinidad.

On the eighth day, at noon, we spoke the lonely island of Sombrero with its lighthouse and black keepers whose only company is the passing steamer. The man at the wheel ported his helm a spoke and we steamed between Saba and Statia to lose sight of land for another day -- my first in the Caribbean. The warm trade wind, the skittering of flying fish chased by tuna or the swift dorade, and the rigging of awnings proclaimed that we were now well within the tropics. The next morning I awoke with the uneasy feeling that all motion had ceased and that we were now lying in smooth water. I stepped on deck in my pajamas to feel for the first time the soft pressure of the tepid morning breeze of the islands.

We lay under the lee of a high island whose green mass rose, surf-fringed, from the deep blue of the Caribbean to the deep blue of the morning sky with its white clouds forever coming up from behind the mountains and sailing away to the westward. Off our port bow the grey buildings of a coast town spread out along the shores and crept up the sides of a hill like lichen on a rock. From the sonorous bell in a church tower came seven deep notes which spread out over the waters like a benediction. There was no sign of a jetty or landing place, not even the usual small shipping or even a steamer buoy, and I was wondering in a sleepy way where we should land when a polite English voice broke in, "We are justly proud of the beautiful harbor which you are to see for the first time I take it. "

I fetched up like a startled rabbit to behold a "West Indie" gentleman standing behind me, "starched from clew to earing" as Captain Slocum put it, and speaking a better English than you or I. It was the harbormaster. I was now sufficiently awake to recall from my chart that the harbor of St. George's is almost landlocked. As we stood and talked, the clanking windlass lifted our stockless anchor with its load of white coral sand and the steamer slowly headed for shore.

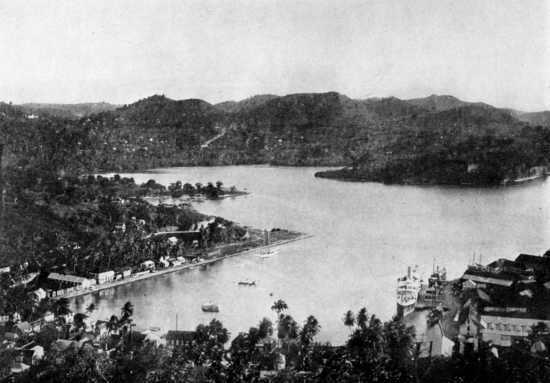

Carénage of St. George's Grenada

The land under a rusty old fort seemed to melt away before our bows and we slipped through into the carénage of St. George's. We crept in till we filled the basin like a toy ship in a miniature harbor. From the bridge I was looking down upon a bit of the old world in strange contrast, as my memory swung back across two thousand miles of Atlantic, to the uncouth towns of our north. The houses, with their jalousied windows, some of them white but more often washed with a subdued orange or yellow, were of the French régime, their weathered red tile roofs in pleasing contrast to the strong green of the surrounding hills.

Here in the old days, ships came to be careened in order to rid their bottoms of the dread teredo. Under our forefoot, in the innermost corner of the harbor, pirate ships were wont to lie, completely hidden from the view of the open sea. At one time this was a hornets nest, unmolested by the bravest, for who would run into such a cul-de-sac protected as it was by the forts and batteries on the hills above?

Moored stern-to along the quays, was a fleet of small trading sloops, shabby in rig and crude of build, waiting for cargoes from our hold. Crawling slowly across the harbor under the swinging impulse of long sweeps, was a drogher piled high with bags of cocoa, a huge-bodied bug with feeble legs.

Moored stern-to along the quays was a fleet of small trading sloops, shabby in rig and crude of build.

Along the mole on the opposite side of the carénage straggled an assortment of small wooden shacks, one and two-storied, scarcely larger than play houses. Among these my eyes came to rest on something which was at once familiar. There stood a small cotton ginnery with shingled roof and open sides, an exact counterpart of a corncrib. I did not then know that in this shed I should spend most of my days while in St. George's.

The blast of our deep-throated whistle stirred the town into activity as a careless kick swarms an anthill with life, and the busy day of the quay began as we were slowly warped-in to our dock.

A last breakfast with the Captain and Mate and I was ashore with my trunk and gear. The Yakaboo, a mere toy in the clutch of the cargo boom, was yanked swiftly out of the hold and lightly placed on the quay where she was picked up and carried into the customhouse by a horde of yelling blacks. Knowing no man, I stood there for a moment feeling that I had suddenly been dropped into a different world. But it was only a different world because I did not know it and as for knowing no man -- I soon found that I had become a member of a community of colonial Englishmen who received me with open arms and put to shame any hospitality I had hitherto experienced. As the nature of my visit became known, I was given all possible aid in preparing for my voyage. A place to tune up the Yakaboo? A young doctor who owned the little ginnery on the far side of the carénage gave me the key and told me to use it as long as I wished.

The market place of St. George's Grenada.

I now found that the cruise I had planned was not altogether an easy one. According to the pilot chart for the North Atlantic, by the little blue wind-rose in the region of the lower Antilles, or Windward Islands as they are called, I should find the trade blowing from east to northeast with a force of four, which according to Beaufort's scale means a moderate breeze of twenty-three miles an hour. Imagine my surprise, therefore, when I found that the wind seldom blew less than twenty miles an hour and very often blew a whole gale of sixty-five miles an hour. Moreover, at this season of the year, I found that the "trade" would be inclined to the northward and that my course through the Grenadines -- the first seventy miles of my cruise -- would be directly into the wind's eye.

I had been counting on that magical figure (30) in the circle of the wind-rose, which means that for every thirty hours out of a hundred one may here expect "calms, light airs, and variables." Not only this, but, I was informed that I should encounter a westerly tide current which at times ran as high as six knots an hour. To be sure, this tide current would change every six hours to an easterly set which, though it would be in my favor, would kick up a sea that would shake the wind out of my sails and almost bring my canoe to a standstill.

Nor was this all. The sea was full of sharks and I was told that if the seas did not get me the sharks would. Seven inches of freeboard is a small obstacle to a fifteen-foot shark. Had the argument stopped with these three I would at this point gladly have presented my canoe to His Excellency the Governor, so that he might plant it on his front lawn and grow geraniums in the cockpit. Three is an evil number if it is against you but a fourth argument came along and the magic triad was broken. If seas, currents, and sharks did not get me, I would be overcome by the heat and be fever-stricken.

I slept but lightly that first night on shore. Instead of being lulled to sleep by the squalls which blew down from the mountains, I would find myself leaning far out over the edge of the bed trying to keep from being capsized by an impending comber. Finally my imagination having reached the climax of its fiendish trend, I reasoned calmly to myself. If I would sail from island to island after the manner of the Carib, why not seek out the native and learn the truth from him ? The next morning I found my man, with the blood of the Yaribai tribe of Africa in him, who knew the winds, currents, sharks, the heat, and the fever. He brought to me the only Carib on the island, a boy of sixteen who had fled to Grenada after the eruption in Saint Vincent had destroyed his home and family.

From these two I learned the secret of the winds which depend on the phases of the moon. They told me to set sail on the slack of the lee tide and cover my distance before the next lee tide ran strong. They pointed out the fever beaches I should avoid and told me not to bathe during the day, nor to uncover my head -- even to wipe my brow. I must never drink my water cold and always put a little rum in it -- and a hundred other things which I did not forget. As for the "shyark" -- "You no troble him, he no bodder you." "Troble" was used in the sense of tempt and I should therefore never throw food scraps overboard or troll a line astern. I also learned -- this from an Englishman who had served in India -- that if I wore a red cloth, under my shirt, covering my spine, the actinic rays of the sun would be stopped and I should not be bothered by the heat.

It was with a lighter heart, then, that I set about to rig my canoe -- she was yet to be baptized -- and to lick my outfit into shape for the long cruise to the northward. I could not have wished for a better place than the cool ginnery which the doctor had put at my disposal. Here with my Man Friday, I worked through the heat of the day -- we might have been out of doors for the soft winds from the hills filtered through the open sides, bringing with them the dank odor of the moist earth under shaded cocoa groves. Crowded about the wide-open doors like a flock of strange sea fowl, a group of black boatmen made innumerable comments in their bubbling patois, while their eyes were on my face in continual scrutiny.

And now, while I stop in the middle of the hot afternoon to eat delicious sponge cakes and drink numerous glasses of sorrel that have mysteriously found their way from a little hut near by, it might not be amiss to contemplate the Yakaboo through the sketchy haze of a pipeful of tobacco. She did not look her length of seventeen feet and with her overhangs would scarcely be taken for a boat meant for serious cruising. Upon close examination, however, she showed a powerful midship section that was deceiving and when the natives lifted her off the horses -- "O Lard! she light!" -- wherein lay the secret of her ability. Her heaviest construction was in the middle third which embodied fully half of her total weight. With her crew and the heavier part of the outfit stowed in this middle third she was surprisingly quick in a seaway. With a breaking sea coming head on, her bow would ride the foamy crest while her stern would drop into the hollow behind, offering little resistance to the rising bow.

She had no rudder, the steering being done entirely by the handling of the main sheet. By a novel construction of the centerboard and the well in which the board rolled forward and aft on sets of sheaves, I could place the center of lateral resistance of the canoe's underbody exactly below the center of effort of the sails with the result that on a given course she would sail herself. Small deviations such as those caused by waves throwing her bow to leeward or sudden puffs that tended to make her luff were compensated for by easing off or trimming in the mainsheet. In the absence of the rudder-plane aft, which at times is a considerable drag to a swinging stern, this type of canoe eats her way to windward in every squall, executing a "pilot's luff" without loss of headway, and in puffy weather will actually fetch slightly to windward of her course, having more than overcome her drift.

She was no new or untried freak for I had already cruised more than a thousand miles in her predecessor, the only difference being that the newer boat was nine inches greater in beam. On account of the increased beam it was necessary to use oars instead of the customary double paddle. I made her wider in order to have a stiffer boat and thus lessen the bodily fatigue in sailing the long channel runs.

She was divided into three compartments of nearly equal length -- the forward hold, the cockpit, and the afterhold. The two end compartments were accessible through watertight hatches within easy reach of the cockpit. The volume of the cockpit was diminished by one half by means of a watertight floor raised above the waterline -- like the main deck of a ship. This floor was fitted with circular metal hatches through which I could stow the heavier parts of my outfit in the hold underneath. The cockpit proper extended for a length of a little over six feet between bulkheads so that when occasion demanded I could sleep in the canoe.

Her rig consisted of two fore and aft sails of the canoe type and a small jib.

An increasing impatience to open the Pandora's Box which was waiting for me, hurried the work of preparation and in two weeks I was ready to start. The Colonial Treasurer gave me a Bill of Health for the Yakaboo as for any ship and one night I laid out my sea clothes and packed my trunk to follow me as best it could.

On the morning of February ninth I carried my outfit down to the quay in a drizzle. An inauspicious day for starting on a cruise I thought. My Man Friday, who had evidently read my thoughts, hastened to tell me that this was only a little "cocoa shower." Even as I got the canoe alongside the quay the sun broke through the cloud bank on the hill tops and as the rain ceased the small crowd which had assembled to see me off came out from the protection of doorways as I proceeded to stow the various parts of my nomadic home. Into the forward compartment went the tent like a reluctant green caterpillar, followed by the pegs, sixteen pounds of tropical bacon, my cooking pails and the "butterfly," a powerful little gasoline stove. Into the after compartment disappeared more food, clothes, two cans of fresh water, fuel for the "butterfly," films in sealed tins, developing outfit and chemicals, ammunition, and that most sacred of all things -- the ditty bag.

Under the cockpit floor I stowed paint, varnish, and a limited supply of tinned food, all of it heavy and excellent ballast in the right place. My blankets, in a double oiled bag, were used in the cockpit as a seat when rowing. Here I also carried two compasses, an axe, my camera, and a chart case with my portfolio and log. I had also a high-powered rifle and a Colt's thirty-eight-forty.

With all her load, the Yakaboo sat on the water as jaunty as ever. The golden brown of her varnished topsides and deck, her green boot-top and white sails made her as inviting a craft as I had ever stepped into.

I bade good-bye to the men I had come to know as friends and with a shove the canoe and I were clear of the quay. The new clean sails hung from their spars for a moment like the unprinted leaves of a book and then a gentle puff came down from the hills, rippled the glassy waters of the carénage and grew into a breeze which caught the canoe and we were sailing northward on the weather tide. I have come into the habit of saying "we," for next to a dog or a horse there is no companionship like that of a small boat. The smaller a boat the more animation she has and as for a canoe, she is not only a thing of life but is a being of whims and has a sense of humor. Have you ever seen a cranky canoe unburden itself of an awkward novice and then roll from side to side in uncontrollable mirth, having shipped only a bare teacupful of water? Even after one has become the master of his craft there is no dogged servility and she will balk and kick up her heels like a skittish colt. I have often "scended" on the face of a mountainous following sea with an exhilaration that made me whoop for joy, only to have the canoe whisk about in the trough and look me in the face as if to say, "You fool, did you want me to go through the next one ?" Let a canoe feel that you are afraid of her and she will become your master with the same intuition that leads a thoroughbred to take advantage of the tremor he feels through the reins. At every puff she will forget to sail and will heel till her decks are under. Hold her down firmly, speak encouragingly, stroke her smooth sides and she will fly through a squall without giving an inch. We were already acquainted for I had twice had her out on trial spins and we agreed upon friendship as our future status.

It has always been my custom to go slow for the first few days of a cruise, a policy especially advisable in the tropics. After a morning of delightful coasting past the green hills of Grenada, touched here and there with the crimson flamboyant like wanton splashes from the brush of an impressionist, and occasional flights over shoals that shone white, brown, yellow and copper through the clear bluish waters, I hauled the Yakaboo up on the jetty of the picturesque little coast town of Goyave and here I loafed through the heat of the day in the cool barracks of the native constabulary. I spent the night on the hard canvas cot in the Rest Room.

It was on the second day that the lid of Pandora's Box sprang open and the imps came out. My log reads : "After beating for two hours into a stiff wind that came directly down the shore, I found that the canoe was sinking by the head and evidently leaking badly in the forward compartment. Distance from shore one mile. The water was pouring in through the centerboard well and I discovered that the bailing plugs in the cockpit floor were useless so that she retained every drop that she shipped. I decided not to attempt bailing and made for shore with all speed. Made Duquesne Point at 11 A.M., where the canoe sank in the small surf."

She lay there wallowing like a contented pig while I stepped out on the beach. "Well!" she seemed to say, "I brought you ashore -- do you want me to walk up the beach?" A loaded canoe, full of water and with her decks awash, is as obstinate as a mother-in-law who has come for the summer -- and I swore.

My outfit, for the most part, was well protected in the oiled bags which I had made. It was not shaken down to a working basis, however, and I found a quantity of dried cranberries in a cotton bag -- a sodden mass of red. With a yank of disgust, I heaved them over my shoulder and they landed with a grunt. Turning around I saw a six-foot black with a round red pattern on the bosom of his faded cotton shirt, wondering what it was all about. I smiled and he laughed while the loud guffaws of a crowd of natives broke the tension of their long silence. The West Indian native has an uncomfortable habit of appearing suddenly from nowhere and he is especially fond of following a few paces behind one on a lonely road. As for being able to talk to these people, I might as well have been wrecked on the coast of Africa and tried to hold discourse with their ancestors. But the men understood my trouble and carried my canoe ashore where I could rub beeswax into a seam which had opened wickedly along her forefoot.

The tall native whom I hit in the chest with the bag of cranberries. On the beach at Duquesne Point.

Picturing a speedy luncheon over the buzzing little "butterfly" I lifted it off its cleats in the forward compartment, only to find that its arms were broken. The shifting of the outfit in the seaway off shore had put the stove out of commission. I was now in a land where only woodworking tools were known so that any repairs were out of the question. I was also in a land where the sale of gasoline was prohibited.* My one gallon of gasoline would in time have been exhausted, a philosophical thought which somewhat lessened the sense of my disappointment. And let this be a lesson to all travelers in strange countries -- follow the custom of the country in regard to fires and cooking.

* On account of the danger of its use in the hands of careless natives.

The breaking of the "butterfly" only hastened my acquaintance with the delightful mysteries of the "coal" pot. Wood fires are but little used in these islands for driftwood is scarce and the green wood is so full of moisture that it can with difficulty be made to burn. Up in the hills the carbonari make an excellent charcoal from the hard woods of the tropical forests and this is burned in an iron or earthenware brazier known as the coalpot.

Iron Coal-Pot

By means of the sign language, which consisted chiefly in rubbing my stomach with one hand while with the other I put imaginary food into my mouth, the natives understood my need and I soon had one of my little pails bubbling over a glowing coalpot.

The promise of rain warned me to put up my tent although I could have been no wetter than I was. Food, a change of dry clothes and a pipe of tobacco will work wonders at a time like this and as I sat in my tent watching the drizzle pockmark the sands outside, I began to feel that things might not be so bad after all. This, however, was one of those nasty fever beaches against which my Man Friday had warned me, so that with the smiling of the sun at three o'clock, I was afloat again. The Yakaboo had been bullied into some semblance of tightness. By rowing close along shore we reached Tangalanga Point without taking up much water.

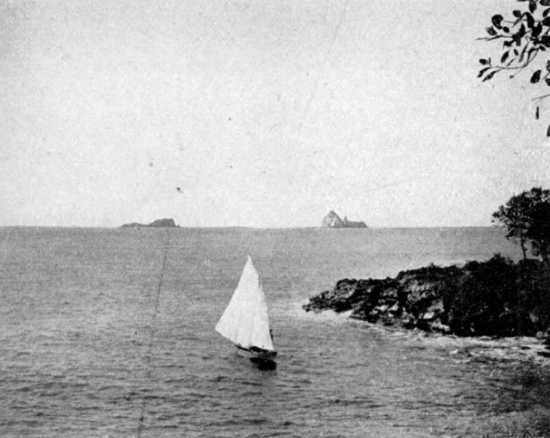

I was now at the extreme northern end of Grenada and could see the Grenadines that I should come to know so well stretching away to windward.** They rose, mountain peaks out of the intense blue of the sea, picturesque but not inviting. As I looked across the channel, whitened by the trade wind which was blowing a gale, I wondered whether after all I had underestimated the Caribbean. Sauteurs lay some two miles around the point and I now set sail for the first time in the open sea.

**In these parts northeast and windward are

synonymous, also southwest and leeward.

In my anxiety lest the canoe should fill again I ran too close to the weather side of the point and was caught in a combing sea which made the Yakaboo gasp for breath. She must have heard the roar of the wicked surf under her lee for she shouldered the green seas from her deck and staggered along with her cockpit full of water till we were at last safe, bobbing up and down in the heavy swell behind the reef off Sauteurs. The surf was breaking five feet high on the beach and I dared not land even at the jetty for fear of smashing the canoe.

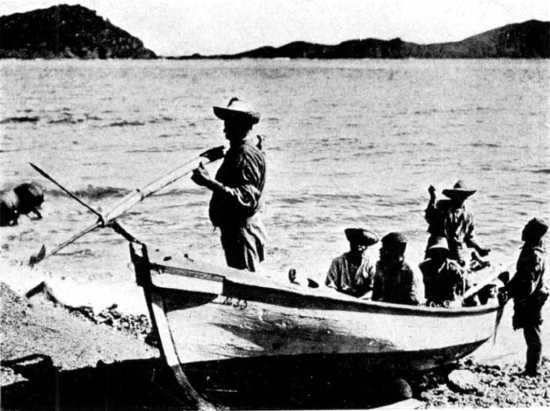

A figure on the jetty motioned to a sloop which I ran alongside. The outfit was quickly transferred to the larger boat and the canoe tailed off with a long scope of line. In the meantime a whaleboat was bobbing alongside and I jumped aboard. As we rose close to the jetty on a big sea, a dozen arms reached out like the tentacles of an octopus and pulled me up into their mass while the whaleboat dropped from under me into the hollow of the sea.

Whatever my misfortunes may be, there is always a law of compensation which is as infallible as that of Gravity. One of those arms which pulled me up belonged to Jack Wildman, a Scotch cocoa buyer who owned a whaling station on Île-de-Caille, the first of the Grenadines. By the time we reached the cocoa shop near the end of the jetty the matter was already arranged. Jack would send for his whalers to convoy me to his island and there I could stay as long as I wished. The island, he told me, was healthy and I could live apart from the whalers undisturbed in the second story of his little whaling shack. Here I could overhaul my outfit when I did not care to go chasing humpbacks, and under the thatched roof of the tryworks I could prepare my canoe in dead earnest for the fight I should have through the rest of the islands.

That night I slept on the stiff canvas cot in the Rest Room of the police station -- a room which is reserved by the Government for the use of traveling officials, for there are no hotels or lodging houses in these parts. From where I lay, I could look out upon the channel bathed in the strong tropical moonlight. The trade which is supposed to drop at sunset blew fresh throughout the night and by raising my head I could see the gleam of white caps. For the first time I heard that peculiar swish of palm tops which sounds like the pattering of rain. Palmer, a member of the revenue service, who had come into my room in his pajamas, explained to me that the low driving mist which I thought was fog was in reality spindrift carried into the air from the tops of the seas. My thoughts went to the Yakaboo bobbing easily at the end of her long line in the open roadstead. All the philosophy of small boat sailing came back to me and I fell asleep with the feeling that she would carry me safely through the boisterous seas of the Grenadine channel.

CHAPTER II

WHALING AT ÎLE-DE-CAILLE

THERE were thirteen of them when I landed on Île-de-Caille -- the twelve black whalemen who manned the boats and the negress who did the cooking -- and they looked upon me with not a little suspicion.

What manner of man was this who sailed alone in a canoe he could almost carry on his back, fearing neither sea nor jumbie, the hobgoblin of the native, and who now chose to live with them a while just to chase "humpbacks"? Jack Wildman was talking to them in their unintelligible patois, a hopeless stew of early French and English mixed with Portuguese, when I turned to José Olivier and explained that now with fourteen on the island the spell of bad luck which had been with them from the beginning of the season would end. The tone of my voice rather than what I said reassured him.

"Aal roit," he said, "you go stroke in de Aactive tomorrow."Between Grenada and Saint Vincent, the next large island to the north, lie the Grenadines in that seventy miles of channel where "de lee an' wedder toid" alternately bucks and pulls the northeast trades and the equatorial current, kicking up a sea that is known all over the world for its deviltry. Île-de-Caille is the first of these.

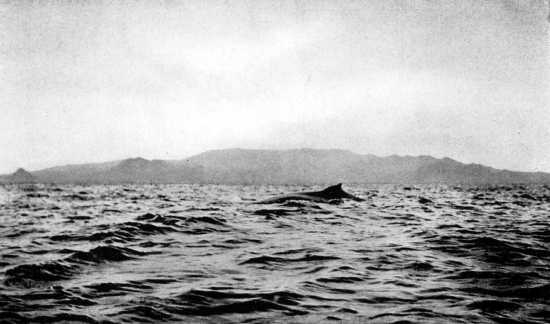

In this channel from January to May, the humpback whale, megaptera versabilis, as he is named from the contour of his back, loafs on his way to the colder waters of the North Atlantic. For years the New Bedford whaler has been lying in among these islands to pick up crews, and it is from him that the negro has learned the art of catching the humpback.

In This Channel From January to May, the Humpback Loafs On His Way to the Colder Waters of the North Atlantic.

While the humpback is seldom known to attack a boat, shore whaling from these islands under the ticklish conditions of wind and current, with the crude ballasted boats that go down when they fill and the yellow streak of the native which is likely to crop out at just the wrong moment, is extremely dangerous and the thought of it brings the perspiration to the ends of my fingers as I write this story. One often sees a notice like this : "May 1st, 1909. -- A whaleboat with a crew of five men left Sauteurs for Union Island ; not since heard of."

The men were not drunk, neither was the weather out of the ordinary. During the short year since I was with them* four of the men I whaled with have been lost at sea. With the negro carelessness is always a great factor, but here the wind and current are a still greater one. Here the trade always seems to blow strongly and at times assumes gale force "w'en de moon chyange."

*This was written in 1912.

This wind, together with the equatorial current, augments the tide which twice a day combs through the islands in some places as fast as six knots an hour.

During the intervals of weather tide the current is stopped somewhat, but a sea is piled up which shakes the boat as an angry terrier does a rat. It is always a fight for every inch to windward, and God help the unfortunate boat that is disabled and carried away from the islands into the blazing calm fifteen hundred miles to leeward. For this reason the Lesser Antilles from Trinidad to Martinique are known as the Windward Islands.

And so these fellows have developed a wonderful ability to eat their way to windward and gain the help of wind and tide in towing their huge catches ashore. Even a small steamer could not tow a dead cow against the current, as I found out afterward. While the humpback is a "shore whale," the more valuable deep-water sperm whale is also seen and occasionally caught. True to his deep-water instinct he usually passes along the lee of the islands in the deeper waters entirely out of reach of the shore whaler who may see his spout day after day only a few tantalizing miles away. A sperm whale which by chance got off the track was actually taken by the men at Bequia, who in their ignorance threw away that diseased portion, the ambergris, which might have brought them thousands of dollars and kept them in rum till the crack of doom.

As we stood and talked with José, my eyes wandered over the little whaling cove where we had landed, almost landlocked by the walls of fudge-like lava that bowled up around it. The ruined walls of the cabaret, where in the days of Napoleon rich stores of cotton and sugar were kept as a foil for the far richer deposit of rum and tobacco hidden in the cave on the windward side, had their story which might come out later with the persuasion of a little tobacco.

The tryworks, like vaults above ground with the old iron pots sunk into their tops, gave off the musty rancid smell of whale oil that told of whales that had been caught, while a line drying on the rocks, one end of it frayed out like the tail of a horse, told of a wild ride that had come to a sudden stop. But most interesting of all were the men -- African -- with here and there a shade of Portuguese and Carib, or the pure Yaribai, superstitious in this lazy atmosphere where the mind has much time to dwell on tales of jumbie and lajoblesse,* moody and sullen from the effects of a disappointing season. So far they had not killed a whale and it was now the twelfth of February.

* The spirits of negro women who have died in illegitimate childbirth.

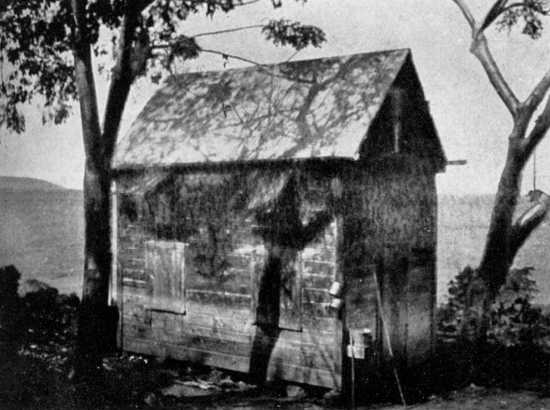

But even the natives were becoming uneasy in the heat of the noon and at a word from José two of them picked up the canoe and laid her under the tryworks roof while the rest of us formed a caravan with the outfit and picked our way up the sharp, rocky path to the level above where the trade always blows cool.

Here Jack had built a little two-storied shack, the upper floor of which he reserved for his own use when he visited the island. This was to be my home. The lower part was divided into two rooms by a curtain behind which José, as befitting the captain of the station, slept in a high bed of the early French days. In the other room was a rough table where I could eat and write my log after a day in the whaleboats, with the wonderful sunset of the tropics before me framed in the open doorway.

Jack's Shack on Ile-de-Caille Where I Made My Home

I later discovered that the fractional member of the station, a small male offshoot of the Olivier family, made his bed on a pile of rags under the table. We were really fourteen and a half. In another sense he reminded me of the fraction, for his little stomach distended from much banana and plantain eating protruded like the half of a calabash. A steep stair led through a trap door to my abode above. This I turned into a veritable conjurer's shop. From the spare line which I ran back and forth along the cross beams under the roof, I hung clothes, bacon, food bags, camera, guns and pots, out of the reach of the enormous rats which overrun the island. On each side, under the low roof, were two small square windows through which, by stooping, I could see the Caribbean. By one of these I shoved the canvas cot with its net to keep out the mosquitoes and tarantulas. I scarcely know which I dreaded most. Bars on the inside of the shutters and a lock on the trap door served to keep out those Ethiopian eyes which feel and handle as well as look.

Near the shack was a cabin with two rooms, one with a bunk for the cook. The other room was utterly bare except for wide shelves around the sides where the whalemen slept, their bed clothing consisting for the most part of worn out cocoa bags.

Almost on a line between the cabin and the shack stood the ajoupa, a small hut made of woven withes, only partially roofed over, where the cook prepared the food over the native coalpots. As I looked at it, I thought of the similar huts in which Columbus found the gruesome cannibal cookery of the Caribs when he landed on Guadeloupe. A strange place to be in, I thought, with only the Scotch face of Jack and the familiar look of my own duffle to remind me of the civilization whence I had come. And even stranger if I had known that later in one of these very islands I should find a descendant of the famous St.-Hilaire family still ruling under a feudal system the land where her ancestors lived like princes in the days when one of them was a companion of the Empress Josephine.

Ajoupa - A Reminder of Carib Days

Even our meal was strange as we sat by the open doorway and watched the swift currents eddy around the island, cutting their way past the smoother water under the rocks. The jack-fish, not unlike the perch caught in colder waters, was garnished with the hot little "West Indie" peppers that burn the tongue like live coals. Then there was the fat little manicou or 'possum, which tasted like a sweet little suckling pig. I wondered at the skill of the cook, whose magic was performed over a handful of coals from the charred logwood, in an iron kettle or two. Nearly everything is boiled or simmered ; there is little frying and hardly any baking.

With the manicou we drank the coarse native chocolate sweetened with the brown syrupy sugar* of the islands. I did not like it at first, there was a by-taste that was new to me. But I soon grew fond of it and found that it gave me a wonderful strength for rowing in the heavy whaleboats, cutting blubber and the terrific sweating in the tropical heat.

* Muscovado.

As early as 1695 Père Labat in his enthusiasm truly said, "As for me, I stand by the advice of the Spanish doctors who agree that there is more nourishment in one ounce of chocolate than in half a pound of beef."

At sunset Jack left for Grenada in one of the whale boats, and I made myself snug in the upper floor of the shack. Late that night I awoke and looking out over the Caribbean, blue in the strong clear moonlight, I saw the white sail of the returning whaleboat glide into the cove and was lulled to sleep again by the plaintive chantey of the whalemen as they sang to dispel the imaginary terrors that lurk in the shadows of the cove.

"Blo-o-ows!" came with the sun the next morning, followed by a fierce pounding on the underside of the trap door. Bynoe, the harpooner, had scarcely reached the lookout on the top of the hill when he saw a spout only two miles to windward near Les Tantes. The men were already by the boats as I ran half naked down the path and dumped my camera in the stern of the Active by "de bum (bomb) box," as José directed. With a string of grunts, curses and "oh-hee's" we got the heavy boats into the water and I finished dressing while the crews put in "de rock-stone" for ballast. As we left the cove we rowed around the north end of the island, our oars almost touching the steep rocky shore in order to avoid the strong current that swept between Caille and Ronde.

When José said, "You go stroke in de Aactive," I little knew what was in store for me. The twenty-foot oak oar, carried high above the thwart and almost on a line with the hip, seemed the very inbeing of unwieldiness. The blade was scarcely in the water before the oar came well up to the chest and the best part of the stroke was made with the body stretched out in a straight line -- we nearly left our thwarts at every stroke -- the finish being made with the hands close up under our chins. In the recovery we pulled our bodies up against the weight of the oar, feathering at the same time -- a needless torture, for the long narrow blade was almost as thick as it was wide. Why the rowlock should be placed so high and so near the thwart I do not know ; the Yankee whaler places the rowlock about a foot farther aft.

While the humpbacker has not departed widely from the ways of his teacher a brief description of his outfit may not be amiss. His boat is the same large double-ended sea-canoe of the Yankee but it has lost the graceful ends and the easy lines of the New Bedford craft. Almost uncouth in its roughness, the well painted topsides, usually a light grey with the black of the tarred bottom and boot-top showing, give it a shipshape appearance ; while the orderly confusion of the worn gear and the tarry smell coming up from under the floors lend an air of adventure in harmony with the men who make up its crew.

Grenadine whaleboat showing bow and false-chock. The harpoon is poised in the left hand and heaved with the right arm.

The crew of six take their positions beginning with the harpooner in the bow in the following order : bow-oar, mid-oar, tub-oar, stroke and boatsteerer. For the purpose of making fast to the whale the harpooner uses two "irons" thrown by hand. The "iron" is a sharp wrought iron barb, having a shank about two feet long to which the shaft is fastened. The "first" iron is made fast to the end of the whale line, the first few fathoms of which are coiled on the small foredeck or "box." This is the heaving coil and is known as the "box line." The line then passes aft through the bow chocks to the loggerhead, a smooth round oak bitt stepped through the short deck in the stern, around which a turn or two are thrown to give a braking action as the whale takes the line in its first rush.

From the loggerhead, the line goes forward to the tub amidships in which 150 fathoms are coiled down. The "second" iron is fastened to a short warp, the end of which is passed around the main line in a bowline so that it will run freely. In case of accident to the first, the second iron may hold and the bowline will then toggle on the first. Immediately after the whale is struck, the line is checked in such a manner that the heavy boat can gather headway, usually against the short, steep seas of the "trades," without producing too great a strain on the gear. The humpbacker loses many whales through the parting of his line, for his boat is not only heavily constructed but carries a considerable weight of stone ballast "rock-stone" to steady it when sailing. The Yankee, in a boat scarcely heavier than his crew, holds the line immediately after the strike and makes a quick killing. He only gives out line when a whale sounds or shows fight. He makes his kill by cutting into the vitals of the whale with a long pole lance, reserving the less sportsmanlike but more expeditious bomb gun for a last resort, while the humpbacker invariably uses the latter.

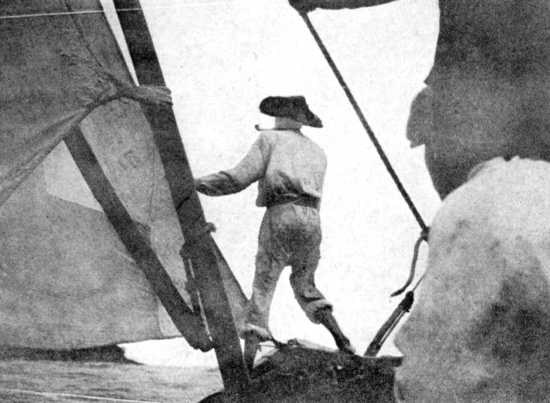

The humpbacker under sail.

A jib and spritsail are carried, the latter having a gaff and boom, becketed for quick hoisting and lowering. Instead of using the convenient "tabernacle" by which the Yankee can drop his rig by the loosening of a pin, the humpbacker awkwardly steps his mast through a thwart into a block on the keel.

Unshipping the rig.

The strike may be made while rowing or under full sail, according to the position of the boat when a whale is "raised." Because of the position of its eyes, the whale cannot see directly fore and aft, his range of vision being limited like that of a person standing in the cabin of a steamer and looking out through the port. The whaler takes advantage of this, making his approach along the path in which the whale is traveling. The early whalemen called the bow of the boat the "head," whence the expression, "taking them head-and-head," when the boat is sailing down on a school of whales.

"Ease-de-oar!" yelled José, for we were now out of the current, bobbing in the open sea to windward of Caille where the "trade" was blowing half a gale. We shipped our oars, banking them over the gunwale with the blades aft. The other boat had pulled up and it was a scramble to see who would get the windward berth.

"You stan' af' an' clar de boom," he said to me, as the men ran the heavy mast up with a rush while the harpooner aimed the foot as it dropped through the hole in the thwart and into its step -- a shifty trick with the dripping nose of the boat pointed skyward one instant and the next buried deep in the blue of the Atlantic.

"Becket de gyaf -- run ou' de boom -- look shyarp!" With a mighty sweep of his steering oar, José pried our stern around and we got the windward berth on the starboard tack. One set of commands had sufficed for both boats ; we were close together, and they seemed to follow up the scent like a couple of joyous Orchas. Now I began to understand the philosophy of "de rock-stone" for we slid along over the steep breaking seas scarcely taking a drop of spray into the boat. As I sat on the weather rail, I had an opportunity to study the men in their element. The excitement of the start had been edged off by the work at the oars. We might have been on a pleasure sail instead of a whale hunt. In fact, there was no whale to be seen for "de balen* soun'," as José said in explanation of the absence of the little cloud of steam for which we were looking. Daniel-Joe, our harpooner, had already bent on his "first" iron and was lazily throwing the end of the short warp of his "second" to the main line while keeping an indefinite lookout over the starboard bow. He might have been coiling a clothesline in the back yard and thinking of the next Policeman's Ball.

* From the French balein, meaning whale.

The bow-oar, swaying on the loose stay to weather, took up the range of vision while we of the weather rail completed the broadside. José, who had taken in his long steering oar and dropped the rudder in its pintles, was "feeling" the boat through the long tiller in that absent way of the man born to the sea. With a sort of dual vision he watched the sails and the sea to windward at the same time. "Wet de leach!" and "Cippie," the tub-oar, let himself down carefully to the lee rail where he scooped up water in a large calabash, swinging his arm aft in a quick motion, and then threw it up into the leach to shrink the sail where it was flapping.

Time after time I was on the point of giving the yell only to find that my eye had been fooled by a distant white cap. But finally it did come, that little perpendicular jet dissipated into a cloud of steam as the wind caught it, distinct from the white caps as the sound of a rattlesnake from the rustle of dry leaves. It was a young bull, loafing down the lee tide not far from where Bynoe had first sighted him.

Again he sounded but only for a short time and again we saw his spout half a mile under our lee. We had oversailed him. As we swung off the wind he sounded. In a time too short to have covered the distance, I thought, José gave the word to the crew who unshipped the rig, moving about soft-footed like a lot of big black cats without making the slightest knock against the planking of the boat.

We got our oars out and waited. Captain Caesar held the other boat hove-to a little to windward of us. Then I remembered the lee tide and knew that we must be somewhere over the bull. Suddenly José whispered, "De wale sing!" I thought he was fooling at first, the low humming coming perhaps from one of the men, but there was no mistaking the sound. I placed my ear against the planking from which it came in a distinct note like the low tone of a 'cello. While I was on my hands and knees listening to him the sound suddenly ceased. "Look!" yelled José, as the bull came up tail first, breaking water less than a hundred yards from us, his immense flukes fully twenty feet out of the water.

Time seemed to stop while my excited brain took in the cupid's bow curve of the flukes dotted with large white barnacles like snowballs plastered on a black wall, while in reality it was all over in a flash -- a sight too unexpected for the camera. Righting himself, he turned to windward, passing close to the other boat. It was a long chance but Bynoe took it, sending his harpoon high into the air, followed by the snaky line.

Once more we had the weather berth and bore down on tem under full sail, Bynoe standing high up on the 'box', holding the forestay.

A perfect eye was behind the strong arm that had thrown it and the iron fell from its height to sink deep into the flesh aft of the fin. As the line became taut, the boat with its rig still standing gathered headway, following the whale in a smother of foam, the sails cracking in the wind like revolver shots while a thin line of smoke came from the loggerhead. Caesar must have been snubbing his line too much, however, for in another moment it parted, leaving a boatload of cursing, jabbering negroes a hundred yards or more from their starting point. The bull left for more friendly waters. The tension of the excitement having snapped with the line, a volley of excuses came down the wind to us which finally subsided into a philosophical, "It wuz de will ob de Lard."

Whaling was over for that day and we sailed back to the cove to climb the rocks to the ajoupa where we filled our complaining stomachs with manicou and chocolate. While we ate the sun dropped behind the ragged fringe of clouds on the horizon and the day suddenly ended changing into the brilliant starlit night of the tropics. Even if we had lost our whale, the spell was at last broken for we had made a strike. Bynoe' s pipe sizzled and bubbled with my good tobacco as he told of the dangers of Kick 'em Jinny or Diamond Rock on the other side of Ronde.

The men drew close to the log where we were sitting as I told of another Diamond Rock off Martinique of which you shall hear in due time. Bynoe in turn told of how he had helped in the rescue of an unfortunate from a third Diamond Rock off the coast of Cayan (French Guiana) where the criminal punishment used to be that of putting a man on the rock at low tide and leaving him a prey to the sharks when the sea should rise. But there was something else on Bynoe's mind. The same thing seemed to occur to Caesar, who addressed him in patois. Then the harpooner asked me :

"An' you not in thees ilan' before?"I lighted my candle lamp and spread my charts out on the ground before the whalers. As I showed them their own Grenadines their wonder knew no bounds Charts were unknown to them. Now they understood the magic by which I knew what land I might be approaching -- even if I had never been there before.

Most of the names of the islands are French or Carib ; even the few English names were unknown to the men, who used the names given to the islands before they were finally taken over by the British. One which interested me was Bird Island, which they called Mouchicarri, a corruption of Mouchoir Carré or Square Handkerchief. This must have been a favorite expression in the old days for a whitened shoal or a low lying island where the surf beats high and white, for there is a Mouchoir Carré off Guadeloupe, another in the Bahamas and we have our own Handkerchief Shoals. From the lack of English names it is not at all unreasonable to suppose that it was a Frenchman who first explored the Grenadines. Columbus, on his hunt for the gold of Veragua, saw the larger islands of Grenada and Saint Vincent from a distance and named them without having set foot on them. Martinique was the first well established colony in the Lesser Antilles and from that island a boatload of adventurers may have sailed down the islands, naming one of the Grenadines Petit Martinique, from their own island, because of its striking similarity of contour, rising into a small counterpart of Pelée. Also, it was more feasible to sail down from Martinique than to buck the wind and current in the long channel from Trinidad.

As the fire in the ajoupa died down, the men drew closer and closer to the friendly light of my candle, away from the spooky shadows, and when I bade them good night they were behind the tightly closed door and shutters of their cabin by the time I had reached my roost in the top of the shack.

For several days after our first strike the cry of "blows" would bring us "all standing" and we would put to sea only to find that the whale had made off to windward or had loafed into those tantalizing currents to leeward where we could see it but dared not follow. Finally our chance came again -- and almost slipped away under our very noses.

We had been following a bull and a cow and calf since sunrise. At last they sounded an hour before sunset. We had eaten no food since the night before and all day long the brown-black almost hairless calves of the men had been reminding me in an agonizing way of the breast of roasted duck. The constant tacking back and forth, the work of stepping and unshipping the rig, the two or three rain squalls which washed the salt spray out of our clothes and made us cold, had tired us and dulled our senses. Suddenly the keen Bynoe, with the eyes of a pelican, gave the yell. There they were, scarcely a hundred yards from us. The bull had gone his way. I was in Caesar's boat this time and as Bynoe was considered the better of the two harpooners we made for the calf and were soon fast.

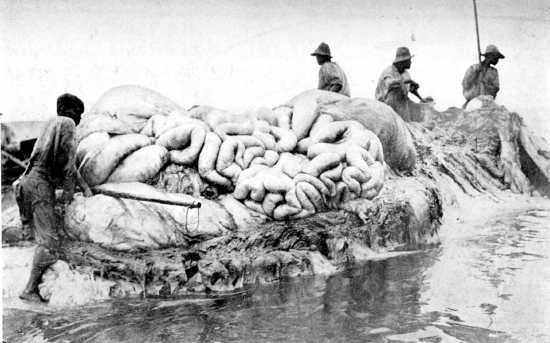

If ever a prayer were answered through fervency our line would have parted and spared this baby -- although it seems a travesty to call a creature twenty-eight feet long a baby. But it was a baby compared to its mother, who was sixty-eight feet long. As the calf was welling up its life blood, giving the sea a tinge that matched the color of the dying sun, the devoted mother circled around us, so close that we could have put our second iron into her.

It is always this way with a cow and her calf. The first or more skillful boat's crew secures the calf while the mother's devotion makes the rest easy for the other boat. There was no slip this time and the program was carried out without a hitch. José bore down in the Active and Daniel-Joe sent his iron home with a yell. We stopped our work of killing for the moment to watch them as they melted away in the fading light, a white speck that buried itself in the darkness of the horizon. It was an all-night row for us, now in the lee tide, now in the weather tide, towing this baby -- a task that seemed almost as hopeless as towing a continent. But we made progress and by morning were back in the cove.

Having eaten three times and cut up the calf, we sailed for Sauteurs late in the afternoon for news of José and the cow. José's flight from Mouchicarri, where we had struck the whales, had been down the windward coast of Grenada. We were met on the jetty by Jack, who told us that the cow had been killed at the other end of Grenada and would not start till the next noon. He had made arrangements for the little coasting steamer, Taw, to tow the carcass up from St. George's.

And so the cow would make the circuit of the island, the first part very much alive, towing a crew of negroes half dead from fright and the last of the way being towed very much dead. While we had been rowing our hearts out, José and his crew had been streaking it behind the whale, not daring to pull up in the darkness for the "kill."

At dawn they dispatched the weakened animal more than thirty miles from their starting point. We learned later that, although the wind and tide had been in their favor and as they neared shore other boats had put out to reach them, they did not reach St. George's till eleven the following night. They had made half a mile an hour.

As we turned in on the floor of Jack's cocoa shop, I began to have visions of something "high" in the line of whale on the morrow. I knew the Taw. She could not possibly tow the whale any faster than three miles an hour and would not leave St. George's till one o'clock the next day. The distance was twenty-one miles, so that by the time she could be cut -- in the whale would have been dead three nights and two days. I no longer regretted the wild night ride I had missed.

The next afternoon we were again in the whaleboat, Jack with us. Our plan was to wait near London Bridge, a natural arch of rocks half way between Sauteurs and Caille and a little to windward. We did this to entice the captain of the Taw as far to windward as possible for we were not at all certain that he would tow the whale all the way to Île-de-Caille. If he brought the whale as far as London Bridge, the two boats might be able to tow the carcass during the night through the remaining three miles to the island so that we could begin to cut-in in the morning.

So we sailed back and forth till at last, as the sun was sinking, we made out the tiny drift of steamer smoke eight miles away. They were not even making the three miles an hour and Bynoe said that the tongue must have swollen and burst the lines, allowing the mouth to open. We began to wonder why they did not cut off the ventral flukes and tow the whale tail first. But the reason came out later.

The moon would be late, and we continued sailing in the darkness without a light, lest the captain should pick us up too soon and cast off the whale in mid-channel where ten whaleboats could not drag her against the current which was now lee. We lost sight of the steamer for an hour or so but finally decided that what we had taken for a low evening star was her masthead light. In another hour we could make out the red and green of her running lights. She was in the clutches of the tide directly to leeward. She was also two miles off her course and we began to wonder why the captain did not give up in disgust and cast the whale adrift. We sailed down to find out.

First the hull of the steamer began to take shape in the velvety darkness ; then as we swung up into the wind we made out the whaleboat some distance astern. As the bow of the steamer rose on a long sea, her after deck lights threw their rays on a low black object upon which the waves were shoaling as on a reef. At the same instant a stray whiff from the trade wind brought us the message. We were doubly informed of the presence of the cow.

But it was not the cow that drew our attention. On the aft deck, leaning far out, stood the captain. His features were distinct in the beams of the range light. Suddenly he started as though he had seen something. Then he bellowed, "Where in hell did you come from?"

"We've been waiting to windward for you ; what's the trouble?""Trouble?" he shrieked, "trouble? -- your damned old whale is fast and I can't get her off."

We guessed the rest. As Bynoe had predicted, the tongue had swollen and burst the lashing that had held the mouth closed. Next the towline had parted. This had happened shortly after the steamer left St. George's and the men who were towing behind in their boat had begged the captain to pass out his steel cable. He didn't know it but it was here that he erred. The whalemen ran the cable through the jaw, bending the end into a couple of hitches. When they started up again, the hitches slipped back and jammed, making it impossible to untie the cable.

Progress had been slow enough under the lee of Grenada but when the steamer got clear of the land she felt the clutches of the current and progress to the northward was impossible. He announced to the pleading whalemen that he was sick of the job and was going to cut loose. But he couldn't. There was not a tool aboard except the engine room wrenches. Not even a file or a cold-chisel.

Jack asked him, "What are you going to do?""Me? -- it's your whale."

"Yes, but you've got it. I don't want it, it's too old now."

And old it was. The smell even seemed to go to windward. But there was only one course left and twelve o'clock found us at Sauteurs, the whale still in possession of the Taw.

The scene of our midnight supper in the cocoa shop that night will long remain in my memory as one of those pictures so strange and far off that one often wonders whether it was a real experience or a fantasy suggested by some illustration or story long since forgotten. We cooked in Jack's little sanctum, railed off at one end of the shop, where the negress brings his tea in the morning and afternoon. At the other end was the small counter with the ledger and scales that brought out the very idea of barter. On the floor space between were bags of cocoa and the tubs in which the beans are "tramped" with red clay for the market. Two coils of new whale line and a bundle

I am firmly convinced that the next morning the odor from that carcass opened the door, walked in and shook me by the shoulders. No one else had done it and I sat up with a start. Shortly after, a courier from the district board brought the following message : (I use the word "courier" for it is the only time I ever saw a native run.)

ST. PATRICK'S DISTRICT BOARD, SECRETARY'S OFFICE,

24th, February, 1911. John S. Wildman, Esq.,SIR : -- In the interest of sanitation, I am instructed to request that the whale's carcass be removed from the harbor within three hours after the service of this notice.I have the honor to be, sir,

Your obedient servant, R.L.B.A., Warden.

We were not unwilling and had what was left of the cow towed out into the current which would carry it far into the Caribbean where for days the gulls could gorge themselves and scream over it in a white cloud. At least that was our intention, but by a pretty piece of miscalculation on the part of Bynoe the carcass fetched up under Point Tangalanga where the last pieces of flesh were removed on the eighth day after the whale's death.

Our work done at Sauteurs, we sailed back to Caille, where we scrubbed out the boats with white coral sand to remove the grease, dried out the lines and coiled them down in the tubs for the next whale.

My real ride behind a humpback came at last in that unexpected way that ushers in the unusual. We were loafing one day near Mouchicarri, lying-to for the moment in a heavy rain squall, when it suddenly cleared, disclosing three whales under our lee. They were a bull, a cow and a yawlin (yearling), with José close on their track. Bynoe hastily backed the jib so that we could "haal aft" and we made a short tack.

Just as we were ready to come about again in order to get a close weather berth of the bull, the upper rudder pintle broke and our chance slipped by. Why Caesar did not keep on, using the steering oar, I do not know. Perhaps it was that yellow streak that is so dangerous when one is depending on the native in a tight place, for we should have had that bull. He was immense.

The rudder was quickly tied up to the stern post, but it was only after two hours of tedious sailing and rowing that we were again upon them. Once more we had the weather berth and bore down on them under full sail, Bynoe standing high up on the "box," holding to the forestay. Except for the occasional hiss of a sea breaking under us, there was not a sound and we swooped down on them with the soft flight of an owl.

As I stood up close to Caesar, I could see the whole of the action. The three whales were swimming abreast, blowing now and then as they rose from a shallow dive. The tense crew, all looking forward like ebony carvings covered with the nondescript rags of a warehouse, seemed frozen to their thwarts. Only one of us moved and he was Caesar, and I noticed that he swung the oar a little to port in order to avoid the bull and take the yawlin. I had guessed right about the yellow streak.

But even the yawlin was no plaything and as he rose right under the bow the sea slid off his mountainous back as from a ledge of black rock, a light green in contrast to the deep blue into which it poured. The cavernous rush of air and water from his snout sprayed Bynoe in the face as he drove the iron down into him. He passed under us, our bow dropping into the swirl left by his tail and I could feel the bump of his back through Caesar's oar.

I wondered for the moment if the boat would trip. There seemed to be no turning, for the next instant the flying spray drove the lashes back into my eyes and I knew we were fast. Blinded for the moment I could feel the boat going over and through the seas, skittering after the whale like a spoon being reeled in from a cast. When I finally succeeded in wiping the lashes out of my eyes there was nothing to be seen ahead but two walls of spray which rose from the very bows of the boat, with Bynoe still clinging to the stay with his head and shoulders clear of the flying water. There was no need to wet the line ; the tub oar was bailing instead.

How the rig came down I do not know and I marvel at the skill or the luck of the men who unshipped the heavy mast in that confusion of motions, for my whole attention was called by the yelling Caesar to the loggerhead, which somehow had one too many turns around it. Caesar was busy with the steering oar, and the men had settled down a little forward of midships to keep the boat from yawing. So I committed the foolhardy trick of jumping over the line as it whizzed past me in a yellow streak and, bracing myself on the port side, I passed my hand aft along the rope with a quick motion and threw off a turn, also a considerable area of skin, of which the salt water gave sharp notice later.

The line was eased and held through this first rush. As the whale settled down to steady flight we threw back that turn and then another, till the tub emptied slower and slower and the line finally came to a stop. We were holding. But we were still going ; it only meant that the yawlin, having gone through his first spurt, had struck his gait ; it was like a continuous ride in the surf. By this time the boat was well trimmed and bailed dry.

"Haal een, now," came from Caesar, and I was again reminded of the missing skin. By the inch first, then by the foot it came, till we had hauled back most of our thousand feet of line. The walls of spray had dropped lower and lower, till we could see the whale ahead of us, his dorsal fin cutting through the tops of the waves. We were now close behind his propelling flukes that came out of the water at times like the screw of a freighter in ballast. Caesar told me to load "de bum lance," and I passed the gun forward to Bynoe. He held it for a moment in pensive indecision -- and then placed it carefully under the box.

He now removed the small wooden pin that keeps the line from bobbing out of the bow chocks, and with the blunt end of a paddle he carefully pried the line out of the chock so that it slid back along the rail, coming to rest against the false chock about three feet abaft the stem. We now swerved off to one side and were racing parallel to the whale opposite his flukes. The bow four surged on the line while I took in the slack at the loggerhead, Caesar wrestling frantically with his steering oar that was cutting through the maelstrom astern.

We were now fairly opposite the yawlin, which measured nearly two of our boat's length. It was one of those ticklish moments so dear to the Anglo-Saxon lust for adventure -- even the negroes were excited beyond the feeling of fear. But at the sight of the bomb gun, as Bynoe took it out from under the box, a feeling of revulsion swept over me and if it were not for the fatal "rock-stone," or the sharks that might get us, I would have wished the gun overboard and a fighting sperm off Hatteras on our line.

The yawlin continued his flight in dumb fear. Fitting his left leg into the half-round of the box, the harpooner raised his gun and took aim. Following the report came the metallic explosion of the bomb inside the whale. Our ride came to an end almost as suddenly as it had begun ; the yawlin was rolling inert at our side, having scarcely made a move after the shot. The bomb had pierced the arterial reservoir, causing death so quickly that we missed the blood and gore which usually come from the blow-hole in a crimson fountain with the dying gasps of the whale. Bynoe explained that one could always tell if the vital spot had been reached :

"If he go BAM! he no good. W'en he go CLING! de balen mus stop." His way of expressing it was perfect, for the "cling" was not unlike the ringing hammer of trapped air in a steam pipe, but fainter.

Luck was with us this time, for we were well to windward of Caille, with a tide that was lee to help us home.

But it was my last whale at Île-de-Caille, and after we had cut him in and set his oily entrails adrift I turned once more to the Yakaboo. I had had enough of humpbacking and one night I packed my outfit and smoked for the last time with the men.

The immense intestines and bladders that looked like a fleet of balloons come to grief.