Alone in the Caribbean

CHAPTER V

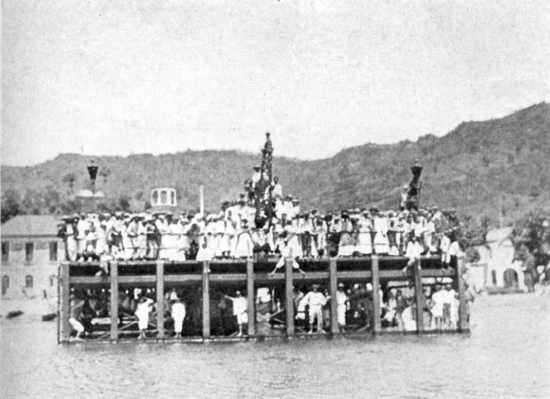

CLIMBING THE SOUFFRIÈRE OF SAINT VINCENT

MY ENTRY into the port of Kingstown was spectacular, but hardly to my liking. The mail sloop from Bequia had spread the news of my coming and as I neared the shore, I saw that the jetty and the beach were black with black people. A rain squall came down from the hills, but it did not seem to dampen the interest of the people nor dim the eye of my camera. I had scarcely stepped out of the canoe when the crowd rushed into the water, lifted her on their shoulders and she continued on her way through a sea of bobbing heads. Direct was her course for the gate of the building which contains the government offices and she at last came to rest in a shaded corner of the patio, where the police are drilled. As I followed in her wake, I said to myself, "She may be without rudder and without skipper and still find her way to a quiet berth." We were in a land-locked harbor, the crowd as a sea outside, beating against the walls.

My own procedure was as strange a performance as that of the Yakaboo. Among the officials in the patio was one who pushed himself forward and gave me a package of mail. He was His Majesty's Postmaster, Mr. Monplaisir.

"Is there anything I can do for you?" asked H.M.P.M., addressing me by my first name."Yes, Monty," -- he was pleased at this -- "you can lead me to a fresh-water shower."

"Come along, then," and the sergeant opened the gate for us. As we walked through the streets, the crowd streaked out behind us like the tail of a comet. We soon gained the house of one Mr. Crichton, where a number of government clerks lived as in a boarding house and where a transient guest might also find lodging. There happened that time to be such a guest, by name, Dr. Theodorini -- optometrist. His mission in life, it seemed, was to relieve the eye strain of suffering natives throughout the West Indies. His most popular prescriptions called for gold-rimmed glasses -- not always a necessity, but undeniably a distinct social asset. We became good friends.

My comet's tail, like any well behaved appendage, tried to follow me into Mr. Crichton's house but the landlord was too quick for it and, as I stepped over the threshold, he bounded against the flimsy door, thus performing a very adroit piece of astronomic surgery. Divested of my tail, I was led to the bath, which proved to be a small separate building erected over a spacious tank with sides waist high. Over the center of the tank drooped a nozzle with a cord hanging down beside it. What an excellent chance to wash the sea water out of my clothes! I pulled the cord and stood under the shower. Monty handed me a cigarette which I puffed under my hat brim.

In the meantime, Dr. Theodorini, whom I had not yet met, began throwing pennies to the baffled crowd from the second story window. It must have been a queer sight could one have viewed it in section. The swearing of the landlord, accompanied by the orchestration of the voices outside and the staccato "Hurrah's" of Theodorini reminded me in a silly way of Tschaikowsky's 1812 overture.

Having washed my clothes, I bathed au naturel and then found to my chagrin that I had brought nothing with me from the canoe. Through the partly opened door I ordered one of the servants to go to my canoe and bring the little yellow bag which contained my spare wardrobe. Dried and unsalted, I emerged from the bath to sit down to a West Indian breakfast at the table of mine host.

My days in Kingstown were mainly occupied in developing the more recent exposures I had made in the Grenadines and in rewashing the films I had developed en route. In the tropics I found that as soon as I had opened a tin of films, it was imperative to expose and develop them as quickly as possible in order to avoid fogging in the excessive heat. Whenever I came to a place like Kingstown where ice was obtainable this was a simple matter, for by the use of the film tank and the changing bag I was independent of a dark room.

On the beaches, however, my chief difficulty was in lowering the temperature of the water, which usually stood at 80° F. -- the "frilling" point for films. Having mixed the developing solution in the tank, I would close it and wrap it carefully in a wet flannel shirt. Then with a line tied to it -- my mizzen halyard served admirably with its three-inch mast ring to hold in my hand -- I would step clear of my tent and whirl the tank around my head at the end of the line. In this way I could bring down the temperature of the liquid to about 75û -- a safe temperature for developing. Often I did not have enough fresh water for washing the developed films and would have to use sea water -- which meant a thorough rewashing such as at Kingstown. Even under these adverse conditions my failures were only ten per cent of the total.

Ice, in these parts, is used mainly in the making of swizzles, as the West Indian cocktails are called, and when, as at Crichton's, I would send for enough ice to chill gallons of swizzles and withdraw silently to my room after dinner, another topic would be added in the speculation which summed me up as "queer chap that."

On the 22nd of March, I sailed out of the roadstead of Kingstown before a stiff breeze which the trade sent around the southern hills like a helping hand. It was only natural that the wind should become contrary off Old Woman Point where it hauled around to the North. Then it changed its mind, crawled up and down the mast a couple of times, and died out in a hot gasp.

The shift from sails to oars in the Yakaboo was quickly made. With a tug and a turn the mizzen was hauled taut and made fast. I worked my lines on "Butler" cleats, a combination of hook and jam cleat that was quick and effective.

A semicircular motion of the hand cleared the line, the same motion reversed made the line fast again. My mizzen boom amidships, I then let go the main halyard and the sail dropped into its lazy jacks like a loose-jointed fan. With three turns of the halyard the furled sail was secured and by making the line fast to its cleat on the port coaming the sail was kept to one side, clear of the cockpit. The lazy jacks held the sail up so that the oar could pass under it without interference. By letting go the mizzen halyard, it likewise fell into its lazy jacks. To furl the mizzen, I pulled taut on a downhaul, the standing parts of which passed around each side of the sail and over the gaff. Thus the gaff was drawn down close to the boom, the line snugly holding the intermediate sail and battens.

These five operations were done in the time it takes a man to remove a case from his pocket and light a cigarette. Then I loosed the light seven-foot oars tied in the cockpit with their blades under the forward decking. With a shove my blanket bag was in the forward end of the cockpit, where it served as my seat when rowing. The rowlock chocks with their sockets and rowlocks were quickly secured in their places on deck, by means of winged nuts that screwed into flush sockets. By the time the man with the cigarette has taken three puffs the Yakaboo is off at a three and a half knot gait.

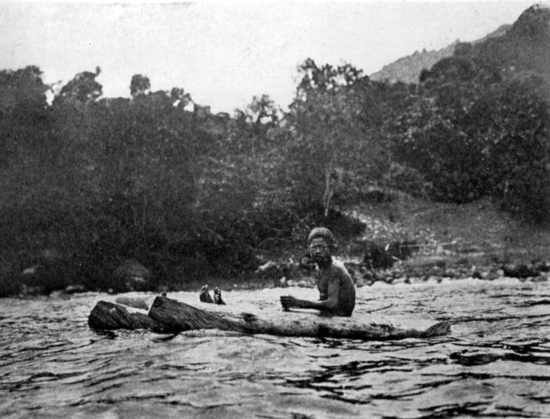

"As I neared the shore I saw that the jetty was black with black people."

The usual appearance of the jetty, boat unloading for the market.

So far, I had done but little rowing in smooth waters and the sense of stealing quietly along the lee coast to enjoy its intimacy was a new pleasure. All these islands, especially the lower ones, have more or less the same formation -- Grenada, Saint Vincent, Saint Lucia, and Dominica. This formation consists of a backbone which rises to a height of from two to three thousand feet and is the main axis of the island with spurs which run down to the Atlantic and the Caribbean, east and west, like the veins of a leaf. The coast is a fascinating succession of points, bays, cliffs, and coves. One may range along shore and find a spot to suit any whim one's fancy may dictate.

I chanced to look around -- to locate my position on the chart -- when I found that I was rowing into a fleet of canoes calmly resting on the heave of the sea like a flock of ducks. They were apparently waiting for me. There was not the usual babble of the native and if I had not turned just then another stroke or two would have shot the Yakaboo into their friendly ambuscade. The canoes were filled with "Black Caribs" -- hence the absence of the babble -- that sub-race which sprang from Bequia nearly two and a half centuries ago.

In 1675, a slave ship from the West Coast of Africa foundered in a gale on the shores of Bequia which at that time was a Carib stronghold. The negroes were good water people and as the ship went down they swam ashore, men, women, and children, where they were well received by the Caribs. What became of the white skipper and his crew one does not hear -- they were presumably murdered.

The Caribs were quick to realize that fortune had sent them a new ally in these negroes whose love for the white man was at a low ebb. The blacks were adopted by the Caribs and a new sub-race was formed. The result was a tribe in which the fighting qualities of both races were distilled to a double strength (an expression which comes naturally enough when one is writing in a rum country). These Black Caribs successfully held the English at bay for a number of years. Nearly a quarter of a century before, the Caribs in Grenada had been completely exterminated by the French and they were now being rapidly driven out of Saint Vincent by the English.

The negro blood very quickly gained ascendancy, as it invariably does, and as far as I could ascertain the traces of the Carib were almost completely obliterated among the Black Caribs whom I saw. The hair is one of the most obvious indices of admixture, varying from the close curly wool of the pure African through diverse shades of dark tow to the straight black of the Indian. Where racial color is well mixed, the hair is often like the frayed end of a hemp rope.

I stopped to talk with them and they begged me to come ashore to see their village of which they were evidently proud. It is called Layou and lies in the bight of a bay by the same name. We landed on a beach furnace of hot black sand. The sand reminded me of iron, and iron reminded me of tetanus. This reminded me that the lockjaw germ is not a rare animal on these inhabited beaches so I put on my moccasins.

As I have implied there was heat. Not alone the stifling heat of a beach where the still air, like a spongy mass, seems to accumulate caloric units but also the heat of a vertical tropic sun, pouring down like rain. My felt hat, stuffed with a red handkerchief, made a small circle of shade which protected my neck when I held my head up but left the tips of my shoulders scorching. My forearms hung gorilla-like from my rolled up sleeves, not bare but covered by a deep tan from which sprang a forest of bleached hairs -- the result of weather. Heaven preserve me from a nooning on a beach like that!

The village consisted of a single row of one-room huts, thatch-roofed and wattle-sided, each standing on four posts as if to hold its body off the blistering sands. The people conducted me along this row of huts on stilts in exactly the way a provincial will take you for a walk down the main street of his town. Instead of turning into the drug store, we fetched up by a large dugout where a quantity of water-nuts (jelly coconuts) were opened. It was the nectar of the Gods.

I felt like an explorer on the coast of Africa being entertained by the people of a friendly tribe. I was touched by their kindly hospitality and shall tell you later of other friendly acts by these coast natives. I do not believe it was curiosity alone that tempted them to beg me to visit their village. True, they crowded around the Yakaboo, but they had the delicacy not to touch it, a trait which usually obtains among rural or coastal natives whether in these islands or civilization. They seemed deeply interested in me and I felt that they were constantly devouring me with their eyes. When I left them, they filled the cockpit of the Yakaboo with bananas and water-nuts trimmed ready to open at a slice from my knife.

As I rowed out into the bay, I nearly ran down a diminutive craft sailing across my bows. There was something about that double rig -- the Yakaboo turned around to look at it as we slid by -- and sure enough it was Yakaboo's miniature! Not far off a small grinning boy sat on a small bobbing catamaran. He had seen the Yakaboo in Kingstown and had made a small model of her -- and so she was known to a place before she herself got there. I left a shilling on the deck of the Little Yakaboo, but she was not long burdened with her precious cargo.

I was again dreaming along shore. Instead of facing the north, as I had while sailing, and looking at new country, I was now looking toward the south and could still see the outlines of the Grenadines and even distant Grenada, a haunting tongue of misty blue that faded into the uncertain southern horizon. The idea seemed to possess me that I should never get out of sight of that outline. Now I saw it with my own eyes, eaten up by the last point astern that had devoured the Grenadines one by one. I looked around me and could see only shores that were new to me within the hour. There was a strange joy in it. I had made a tangible step northward.

The sun was getting low, and as the reflection came from the broken water, miles to leeward, I felt that I was traveling along the edge of the world. No horizon line to denote finality, the sense was of infinity and I fancied the trade wind, which blew high overhead and met the sea offshore, a siren trying to draw me away from land to the unknown of ragged clouds. It was the effect upon my mind of the ceaseless trade and the westerly current.

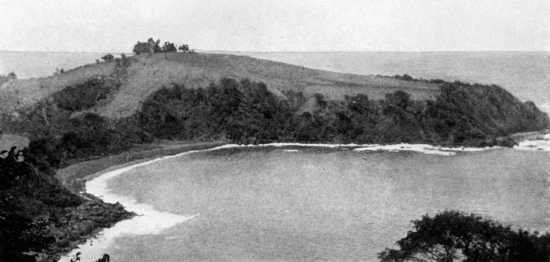

Along the lee coast of St. Vincent near Layou.

With the setting of the sun my row came to an end. I was in the little bay of Château Belaire, at the foot of the Souffrière volcano.

There was a fierce joy of deception in my heart as I sneaked up to the jetty in the dusk and quietly tied my painter to the landing stage. For once I had cheated the native of the small spectacular scene of which he is so fond. As I stepped ashore, dusk gave way to a darkness relieved only by the glow of coalpots through open doors and the smell of frying fish. The stars were not yet in their full glow. I could move about in the murk observing but not observed. I could walk among the fishermen and their garboarded dugouts without the ever-recurrent "Look! de mon!" But I did not walk about for long and for two very good reasons. A lynx-eyed policeman who had discovered the Yakaboo was one, a foot full of sea eggs was the other.

One morning in Kingstown, I went for a sea bath with Monty. It was then I learned that sharks are not the greatest pest of the sea for while incautiously poking among the rocks I managed to fill my foot full of the sharp spines of a sea egg, spines as brittle as glass that break off in the flesh. I had tried to cut them out with my scalpel, but that only tended to increase the damage. Monty had told me the only thing for me to do was to wait till the points worked out of their own accord.

So I hobbled back to the jetty to take possession of my canoe. My plan was to leave the Yakaboo at Château Belaire while I made the ascent of the Souffrière and while I visited the Caribs on the windward side where the surf was high and the rocky beaches more friendly to the thick bottom of a log dugout than a quarter inch skin. So the Yakaboo -- she was becoming an habitué of the police courts -- was unloaded and carried to the station. While I was in the Carib country, the local court was in session and she served as a bench for the witnesses. I hope that her honest spirit permeated upwards through those witnesses so that in the day of judgment they may say, "Once, O Peter, did I speak the truth."

Information regarding the approach and the ascent of the Souffrière was untrustworthy and difficult to obtain. Any number of the natives seemed to have climbed the volcano, but none of them could tell me how to do it -- a little subtlety on their part to force me to hire guides. I engaged my men, brewed a cup of tea, chatted with the police sergeant, and turned in, on the stiff canvas cot in the rest-room, with a sheet over me. I now know how a corpse feels when it is laid out.

My guides awoke me at five in the morning, I cooked a hasty breakfast and was with them in their boat half an hour later. There were two of them and as surly as any raw Swede deck hands I have ever had to do with. For an hour we rowed in silence and then we landed at the mouth of the Wallibu Dry River. With some of these natives, although you may have hired them at their own price to serve you, the feeling seems to be not to serve you and do what you wish them to do but to grudge their effort on your behalf and to make you do what they want you to do. It requires continual insistence on the part of the white man to have, at times, the simplest services performed -- an insistence that makes one nerve-weary and irritable.

My surly guides.

As soon as we stepped ashore, I sat down on a convenient rock to grease and bandage my sore foot They seemed to have forgotten my presence entirely and started up the bed of the river without even looking around to see whether I was coming or not. I let them walk till they were almost out of hearing and then I called them back. When they came to me, not without some little show of temper, I told them in unmistakable words of one syllable and most of them connected by hyphens -- that we had as yet not started to climb the mountain and that at the end of the day's work I should pay them for being guides and not retrievers to nose out the bush ahead of me.

We proceeded up the bed of the Wallibu River which had been made dry in the last eruption (1902) by a deep deposit of volcanic rocks and dust which had forced the water to seek another channel. As we walked between the cañon-like sides, I was reminded of our own Bad Lands and for the first time I felt a bit homesick. These islands have very little in common with our northern country ; even the nature of the people is different. It seemed queer to me to be walking in this miniature cañon with a couple of West Indian natives instead of riding a patient pony and exchanging a monosyllable or two with a Westerner. I longed for the sight of a few bleached cattle bones and perhaps a gopher hole or a friendly rattlesnake.

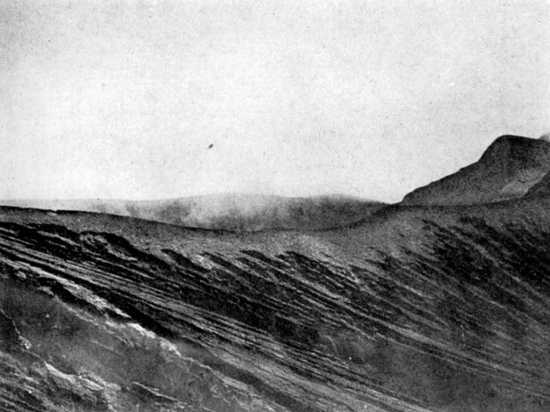

The Wallibu Dry River where we began the ascent. The Soufrière in the distance, it cone hidden in the mist.

A small spur broke the perpendicular face of the northern wall and here we climbed to the upper surface. We were now in bush, most of which was a sort of cane grass, over our heads in height, through which we followed a narrow trail. This upper surface on which we now traveled was in reality the lowest slope of the volcano, a gentle incline where the catenary curve from the crater melts into the horizontal line of the earth's surface. Soon I could see over the top of the grass and found that we were following the ridge of a spur which radiated in a southwesterly direction from the volcano. The ridge itself was not one continuous curve upward but festooned along a series of small peaks between which we dropped down into the bush from time to time. The vegetation between these peaks consisted of the same heavy cane grass we had passed through on the lower slope.

To offset the lack of wind in these valley-like depressions the grass again rose above our heads, keeping the trail well shaded. Thank fortune, the dreaded fer-de-lance does not exist on this island. At about 1,500 feet the vegetation ceased altogether except for a few stray clumps of grass and the greenish fungus that gave the ground a moldy, coppery appearance. There was no sign of the flow of lava on this side of the volcano, merely the rocks and dust which had been thrown up in immense quantities. As we neared the top the wind blew strongly and was cold with the mist torn from the bellies of low-hanging trade clouds. I was fortunate in choosing a day when the crater was at times entirely free of clouds, for only once during the next ten days did I see the top again uncovered, and then for only a few minutes.

Contrary to my wishes, my sullen guides had again taken the bit in their teeth and they started the ascent at a brisk pace which killed them before we were half way up the mountain. My sore foot demanded a steady ground eating pace with no rests. Up till this time they had walked a considerable space ahead of me, this lead gradually decreasing as they tired. I could lose no time and dared not rest, and since I could now find my way perfectly well alone, I went on ahead of them. As I neared the top, the force of the wind became more and more violent till I found it impossible to stand up and I finished the last hundred yards on my hands and knees.

The rim of the crater.

The sight that greeted my eyes as I peered over the rim of the crater literally took my breath away -- that is, what breath the wind had not shoved down to my stomach, for it was blowing a hurricane. I could not at once quite grasp the immensity of the crater -- for its proportions are so perfect that I would not have believed the distance across to the opposite rim to be more than a few hundred yards, -- it is nearly a mile. A thousand feet below me -- held in the bowl of the crater -- was a lake almost half a mile in diameter. During the last splutters of the eruption of 1902 the ejecta had fallen back and this together with the subsiding of the inner slopes of the crater had effectually sealed up the chimney of the volcano.

"A thousand feet below, held in the bowl of the crater, is a lake nearly a half a mile in diameter".

The enormous precipitation which is nearly always going on, due to the striking of the clouds against the crater, has collected in the bottom to form this lake. I hardly knew my old friend the trade wind. He rushed up the windward side of the mountain, boarded the crater, and pounced upon the lake like a demon, spreading squalls in all directions. The surface of the water looked like the blushing surface of a yellow molten metal. Then up the leeward side and over the rim where I hung, he came with the scream of a thousand furies. It was as though the spirits of the unfuneraled dead had come back to haunt the place, day and night. As I pulled the slide out of my camera, to make an exposure, the wind bent it nearly to the breaking point. My hat had long since been a tight roll in my pocket and I lay, head on, my toes dug into the slimy surface of the slope, with my face buried in the hood of my camera and the empty case streaming out behind me.

I spent an hour in scrambling along the rim and then returned to the guides who were resting some distance below. It was still early for I had reached the rim at 8 :30 after a climb of an hour and thirty-two minutes. My barometer registered a height of three thousand and twenty feet and while the climb had been an easy one, the time was not bad for a foot full of sea eggs.

Higher mountains to the north cut off all possibility of seeing Saint Lucia or Martinique, but as I looked to the south, Grenada showed herself and the Grenadines stretched out like stepping stones. Below lay all the vast area that had been laid waste by the eruption. In place of the forests, now buried deep in the volcanic dust and scoria, was a green blanket of grass, bush and small trees that would belie an eruption that had obliterated every sign of green nine years ago. Scrutiny with the field glasses, however, showed innumerable cañons cut through laminae of volcanic deposit with thin layers of soil between. I could almost throw a stone, I thought, into the little village of Château Belaire four miles away, that by some miracle had escaped destruction by a few hundred yards. But my eyes always came to rest on the Caribbean. The rays of the sun, reflected back from myriad waves, too distant to be seen, gave the sea the appearance of a vast sheet of molten metal with here and there a blush where some trade cloud trailed its shadow. The clouds dissolved away into the horizon, sustaining the feeling that there was nothing beyond but infinity.

The sea eggs were now giving sharp notice of their presence and I decided to rush the descent. I had exchanged but few words with my guides. If there had been discontent during the ascent, there was more cause for it now. The customary grog had not been forthcoming, for I never carry spirits on an expedition like this. In case of accident or exposure there are better things that give no after effects of let down. My guides followed me in my downward rush with hardly breath enough for the proper amount of cursing which the occasion demanded. If they said anything about "de dyam Yonkee" I heard it not, for the trade wind would have carried it high over my head. The enjoyment of the chase kept my mind off the pain in my foot. I reached the boat in forty minutes.

When we arrived at Château Belaire I found the Government doctor on his round of the Leeward coast. What a blessed relief it would be to have him inject Some cocaine into my foot and then cut out the miserable sea egg points. But he was as effective as a Christian Scientist -- I should have to wait till I reached Saint Lucia where there was an excellent hospital in Castries and then have the points removed.

Batiste promised better. He was a Yellow Carib whom I had found in Kingstown and whom I had engaged to take me into the Carib country the next day. One of the first books I read on the West Indies was by Frederic Ober and what better boatman could I have than the son of his old Batiste with whom he spent months on the slopes of the volcano camping and hunting the Souffrière bird. "W'en we reach up Carib countrie you see de sea egg come out."

That night I was far away from the Caribbean and I dreamed it was Saturday morning in the city. Outside I could hear the familiar sound of the steps being scrubbed with rotten stone. I could feel the glare of the morning sun that had just risen over the roofs of the houses and was shining on the asphalted street -- "avenue" it was called. Then came the toot-toot of the toy-balloon man, a persistent sound -- too persistent -- and I finally awoke with the sun in my eyes and the noise of Batiste's conch in my ears. With a feeling that my youth was forever a thing of the past and that I had assumed some overwhelming burden, I bounded off the high cot and landed on the sea egg foot. There had been no sea eggs and no overwhelming burden in my young life on that city street. For the sake of company I yelled to Batiste to come and have some tea with me.

At last we were off, I comfortably seated in the after end of the canoe with my family of yellow bags around and under me ; Batiste behind me, steering while we were rowed by two Caribs with Christian names. The canoe was as all canoes of the Lesser Antilles -- in reality a rowboat. The hull proper is a dugout made of the log of the gommier tree. To this has been added a sheer streak to give the craft more freeboard. In adding the sheer streak a wedge is put into the after end so that above water the boat has the appearance of having a dory stern. Oars have long since taken the place of the primitive paddle and because the boat is deep and narrow, having no real bilge at all, she is ballasted with stones. They are ticklish craft, slow-moving and not particularly seaworthy.

We were passing the point between Richmond River and the Wallibu Dry River where I had begun the ascent of the mountain the day before when Batiste said, "You see w'ere de railin' is?" He pointed to a broad tongue of land about two or three acres in extent which for some reason was fenced in. "De boat walk dere before de eriipshun."

Not far from this place we came upon a curious phenomenon which Batiste called "de spinning tide." In the clay-colored water, that surrounded it, was a circular area of blue, sharply defined, about thirty feet in diameter, set in rotary motion by the coastwise current. The coolness of the water suggested the outflow of some submarine spring, probably from under the bed of the Dry River.

One hears but little of the eruption of the Souffrière of Saint Vincent. It was only because there was no large town near the crater of the Souffrière that only sixteen hundred were killed -- a mere handful compared with the twenty-five thousand in the French island. It seems that all these islands, along the arc from Grenada to Saba, lie along a seam where the earth's outer crust is thin. Had the Souffrière of Saint Lucia (which lies between Saint Vincent and Martinique) not been in a semi-active state there would in all probability have been a triple eruption. I found that Pelée and the Souffrière of Saint Vincent have a habit of celebrating together at intervals of approximately ninety years : 1902, 1812, 1718, and there is some mention of disturbances in 1625.

Our chief interest in the eruption of the Souffrière of Saint Vincent is on account of its effect upon the Yellow Carib. This island was the last stronghold of the Caribs in the West Indies and when they were finally subdued and almost exterminated the majority of the few remaining ones were transported by the English to the island of Ruatan near Honduras. The rest were eventually pardoned by the Government and were allowed to settle in various places in the island.

There was for a time a considerable admixture of negro blood, but little by little this was eliminated as the Caribs (Yellow) drew closer and closer together among themselves and began to settle on the windward side of the island at Sandy Bay. Here the Government gave them a considerable grant of land which became known as the "Carib Country." The spread of the Black Carib seems to have stopped shortly after their first union at Bequia. But the Black Carib, more or less a race apart, was more agriculturally inclined than the Yellow Carib, yet possessed the Indian's fondness for the sea.

We find then, before the eruption of 1902, the Yellow Carib to the northeast of the volcano, living more or less in his former state on the windward side of the island ; the Black Carib to the southwest, along the leeward coast, while the negro was more or less evenly distributed throughout the rest of the island. The eruption of the Souffrière differed from that of Pelée in that the volcano of Saint Vincent laid waste a considerable area to windward, devastating most of the Carib Country and killing a goodly number of the Indians. This seems always to have been their favorite spot for as early as 1720 Churchill mentions the fact, and says, "The other side (windward) is peopled by two or three thousand Indians who trade with those about ,' the river Oronoque, on the continent. . . .

Immediately after the eruption, the Government gave the Yellow Caribs land among the Black Caribs along the leeward coast and even went so far as to erect small houses for them -- houses that were far better than their former huts. But the Yellow Caribs were too much Indian to settle down to the tame life of farming among the Black Caribs and little by little they left their comfortable English-made homes and began to steal back to their former haunts ; one by one at first -- then in numbers till there was a well-defined migration. When I visited them -- nine years after the eruption -- all the Yellow Caribs of Saint Vincent were back at Sandy Bay, there being but two individuals outside the island -- one in Carriacou and the other in Grenada.

At one place, where the high cliffs drop sheer into the sea, grudging even a beach, we came upon some Black Caribs fishing from their boats in the deep water. Their method is peculiar and is known as "bulling," probably a corruption of "balling." A single hook on the end of a line is weighted and lowered till it touches bottom. Then the line is hauled in a few feet and a knot is tied so that when the baited hook is lowered it will hang just above the bottom. The line is taken into the boat and the sinker removed from the hook which is now baited with a piece of sardine or smelt. Around this baited hook a ball is formed of meal made of the same small fish. The hook is then gently lowered till the knot indicates that the double bait has reached the haunts of the fish which feeds close to the bottom. With a quick upward jerk the ball is broken away from the hook. The scattered fish-meal draws the attention of the fish which investigates the floating food and presently goes for the large piece hanging in the center. And so like the rest of us who get into trouble when we reach out for the big piece the fish finds that there is a string tied to this food and that the line is too strong for him. The wrist and finger that hold the other end of the line are sensitive to the slightest nibble.

We rounded De Volet Point, which corresponds to Tangalanga on Grenada, and I once more felt the roll of the trades. A sea slopped over the gunwale and wet my leg which I drew into the canoe. We were now all island savages together holding up our ticklish craft by the play of our bodies. I looked across the channel to Saint Lucia with her twin Pitons rising distinct, thirty miles away. Batiste pulled himself together and told me that on very clear days he could see the glint of the sun on the cutlasses in the cane fields on the mountain slopes near Vieux Fort.

"You like some sweet water?" he asked, and at the question my throat went too dry for speech. We turned into a little cove -- you will find it called "Petit Baleine" on the chart, although if a whale swam into it he could never get out unless he could crawl backwards. While the men held the boat off the rocks, Batiste and I jumped ashore with four empty calabashes. A tiny stream which came from high up on the slope of the Souffrière Mountains, with the chill of the mists still in it, poured out from the dense foliage above us, spread itself into a veil of spray, gathered itself together again on a rocky face, and fell into a deep shaded basin into which we put our faces and drank till our paunches gurgled.

How the Caribs Rig a Calabash for Carrying Water

At times it is hard not to be a pig. Then, as if not satisfied with what Nature intended us to carry away, we filled our calabashes. These were as they have always been with the Carib -- left whole with merely a small hole about an inch and a half in diameter in the top. They are carried by means of a wisp of grass with a loop for the fingers in one end and with the other end braided around a small piece of wood that is inserted into the hole to act as a toggle. It is easy to carry water in this way without spilling it for when the calabash is full there is but a small surface for the water to vibrate on. Père Labat mentions a curious use of the calabash in his day. In order to make a receptacle in which valuable papers could be hidden without fear of destruction by moisture a calabash was cut across at a point a quarter or a fifth of its length from the stem end. To cover the opening, another calabash was cut with a mouth somewhat larger than the first one and they were bound together with thongs of the mahaut. This calabash safe was then hidden in the branches of trees that had large leaves for the sake of obscurity. They were called coyembouc by the Caribs who invented them.

We put off again, passing the ruined estate of "Fancy," a mute reminder of that smiling day when destruction had come over the top of the mountains to the south -- one of Nature's back-hand blows. A little beyond, our row of twelve miles came to an end and we beached through the heavy surf at Owia Bay where I found myself in the midst of a group of Yellow Caribs and negroes. I was a bit disappointed till Batiste told me that this was not Point Espagñol. We should have to go the rest of the way by land for the surf at Sandy Bay, he said, was too high to run with the loaded canoe. I wondered at this till I actually saw the surf two days later.

Batiste and his crew packed my family of yellow bags on their heads and marched off on their way to Point Espagñol while I waited for a pony hospitably offered by the manager of an arrowroot estate on the slopes above the bay.

The pony was a heavenly loan but there was a cunning in his eye that did not belong to the realm above. His eye took me in as I mounted him, somewhat stiffly, for the pain of the sea eggs was getting beyond my foot. That eye made careful note that I wore no spurs, neither did I carry a whip nor even a switch. He started off at a brisk pace which he kept up till we were well along the main road. Then he stopped. I clucked and chirruped and whistled and swore. I also beat his leathery sides with my heels. No perceptible inclination to go forward. I talked to him but he did not understand my language. There was something, however, that I knew he would understand and I pulled off my belt. If you must subject by force or punishment, let it be swift, sure and effective. The brute had carelessly neglected to take note of a suspicious lump under my coat which hid a 38-40 Colt. First I circled my legs around his barrel body after the manner of a lead cavalry soldier "Made in Germany." Then with my gun in my left hand and my belt in my right, buckle-end being synonymous with business-end, I gave a warning yell and let him have the buckle in his ribs while the revolver went off close to his left ear. We rapidly caught up with Batiste -- in fact, my steed was even reluctant in slowing down when I pulled him up behind the last Indian.

While my little caravan shuffled along ahead of me, I leisurely enjoyed the scenery of this level bit of road which skirts the slope of the Souffrière Mountains at the very edge where it breaks down to the sea. Some two hundred feet below me an intensely blue sea broke against the rocks into a white foam that washed out into a tracery of fine lace at every lull ; the rocks, the blue, and the foam like that of the Mediterranean along a bit of Italian coast. Landwards the slope rose in a powerful curve, heavily wooded, bearing numerous small peaks, to the Souffrière range which hides the volcano from view till one has reached the extremity of Point Espagñol.

The point is a peninsular-like promontory the top of which rises into two hills. Each of these hills is the site of a small Carib village of about forty-five inhabitants, the last of the Yellow Caribs of the Antilles. After a quick survey I decided upon the farther village which is a bit more to seaward and here I dismounted in the cool shade of the grove which gives the huts a pleasant sense of seclusion. After circling around, much as a dog that is preparing to lie down in the tall grass, I selected a spot on the edge of the little group of huts and set up my tent looking out over the Atlantic which lay some three hundred feet below. Since I could not see the setting of the sun, I faced the tent toward his rising. Here the cool trade wind belied the terrific heat of Sandy Bay below with its incessant roar of surf.

CHAPTER VI.

DAYS WITH A VANISHING RACE.

I NEEDED no introduction to the Caribs, for they had known that I would come since my first meeting with the men in Bequia. They had also learned of my arrival at Château Belaire and that in another day I should be with them. One poor old woman had been watching all day to see me come flying over the Souffrière Mountains. Batiste told her of the Yakaboo and that if it did not fly it was at least rudderless. She consoled herself with, "He sail widout rudder!"

There was some satisfaction in watching me and as I pitched my tent and put my house in order, I had an interested crowd about me that did not use their fingers as well as their eyes with which to see. About a third of the village was there when I arrived. Besides Batiste and his men, those who gathered around my tent were the younger women who were spending the day in baking cassava cakes for the market, the children, and the old women who could do no other work than tend a coalpot or sweep out the huts. The men were either fishing or were down the coast at Georgetown to sell fish and the produce which the women had raised. The women are the farmers and we could see their patient forms moving goat-like along the furrows high up on the mountain slopes where they cultivate cassava, tanniers, and arrowroot.

One of the old women noticed that I was limping and as soon as I had everything ship-shape in my house, she went to her hut and returned with some soft tallow and a coalpot. Batiste said, "You goin' lose sea egg dis night." First she smeared the sole of my foot with the tallow and then lighting a splinter of dry wood from her coalpot she passed the blaze close to the skin, almost blistering the sole of my foot. Then she told me to bandage the foot and not to walk on it -- an unnecessary caution.

With Indian tact, they left me to loaf away the waning afternoon on my old companion, the blanket bag. I had begun the day in an idle way -- let it end that way. There had been many places where I had loafed away the end of an afternoon on my blanket in just this way, but none of them will hold its place in my memory with this camp of mine on the edge of the Carib village. The huts were behind me and in the vista of my tent door there was no form of the ubiquitous native to distract, for there is no depth of character to romance upon when one sees a silent form shuffle along some bush path. Behind me the Caribs were quiet -- I would not have known there were children or dogs in the village. Peace was there with just the rustle of the leaves above me as an accompaniment ; the song of a bird would have been thrilling. Below me the Atlantic rolled under the trade wind through the channel and became the Caribbean. A school of porpoise rounded the point and headed for the Spanish Main, mischief-bent like a fleet of corsairs. Well out in the channel my eye caught a little puff of steam and I knew that it came from a "humpback."

Finally as the sun sent his last long slant across the water whence we had come in the morning, it caught the smoke of the coasting steamer entering the bay of Vieux Fort in Saint Lucia -- a hint of industry to speculate upon. With the shutting down of darkness one of the old women brought me a coalpot and I cooked my supper while the stars came out in an inquisitive way to see what I was doing.

By this time the village had assembled and fed itself. When the people found that I was not unwilling, they flocked around the door of my tent and I chatted with those who could talk English, these in turn interpreted our conversation to the others. After a while, my old sea egg woman of the afternoon -- I could hardly tell one old woman from another, they were like old hickory nuts with the bark on -- said, "Now de sea egg come out." I took off the bandage and she put my foot in her lap. Some one brought a gommier flambeau with its pungent odor that somehow reminded me of a vacant-lot bonfire into which a rubber shoe had found its way.

It would have been one of the best photographs of my whole cruise could I have caught those faces around that burning flambeau. Now for the first time I could really observe them in unconscious pose. Notwithstanding a considerable amount of admixture that must have undergone with the blacks, there was still a satisfying amount of Indian blood left in these people. I said Indian purposely for I do not care to use the expression Carib in this sentence. I believe these people to be more of the peaceful Arawak than the fierce Carib, although time and environment and subjugation may have had this softening effect upon them. How much truth there may be in it I do not know, but the impression seems to be that in these islands the Caribs originally came from the north, advancing from island to island and conquering as they went the peaceful islander, the Arawak, who was the real native of the Lesser Antilles. Upon raiding an Arawak settlement the Caribs would kill most of the men and what women and children they did not eat they took to themselves as wives and slaves. Through their offspring by their Carib masters the Arawak women introduced their language and their softening influence into the tribes so that little by little the nature of the Carib was perceptibly changed. Thus the Arawaks became ultimately the race conquerors. In 1600 Herrera says, "It has been observed that the Caribbees in Dominica and those of Saint Lucia and Saint Vincent scarce understand one another's language," which tends to show that the lingual change was then going on throughout the islands. When I questioned the Caribs of Point Espagñol in regard to the Indians of Dominica they expressed entire ignorance of their fellow savages. These people whom I saw in the light of the flambeau had the softened features of a race dying for the same reason that our pure American is dying -- his country is changing and he cannot change with it. I thought of what Père Labat said of them three hundred years ago -- "Their faces seemed melancholie, they are said to be good people."

Holding my foot close to the light, the old woman pinched the sole on either side of one of the purple marks which indicated the lair of a sea egg point. At the pressure the point launched forth, with scarcely any pain, eased on its way by a small drop of matter. The blistering with the hot grease had caused each minute wound to fester. In the next minute or two the largest of the points, about fourteen in number, were squeezed out. Some of the smaller points along the edge of the sole had not yet festered, but they came out the next morning.

The fun was over, we had had our preliminary chat, the flambeau had burned down, and the village turned in.

So did I.

On "calm" mornings, that is, when the wind is not blowing more than ten or twelve miles an hour, a stiff squall bustles ahead of the sun as if to say, "Get up! By the time you have cooked breakfast the sun will be having a peep to see how you have begun the day. You must take advantage of the cool morning hours, you know," and in a moment is rushing away toward Honduras. And so it was this morning. Confound Nature and her alarm clock that sprinkled in through my open door ! -- but after all she was right.

Fishing was the order of the day and after the sun is up it takes but a short time to warm the black sands of the bay below to a hellish heat. My old woman produced her coalpot -- it seemed to be kindled with the everlasting flame of the Roman Vestals -- and I soon had my chocolate cooking and my bacon frying while I bade a not reluctant adieu to the last few sea egg points. My foot was free of pain and when I walked I could have sworn that there had been nothing like sea egg points in it the day or even the week before. I stuffed a few biscuits in a clothes bag, dressed my camera in its sea togs, and was off with the fishermen to the beach. There were twelve besides myself, four to a boat, two to row and two to fish -- I should be the fifth in Batiste's boat.

The morning was still fresh from the cool night air as we filed down the cliff road to the beach. The surface of the sand was still dew damp. There were three dug-outs waiting for us under the protection of a thatched roof supported by poles, as if some queer four-legged shore bird had just laid them. There was no end of puttering before we could start, a bit of gear to be overhauled, a stitch or two to be taken in a sail so patched that I doubt whether there was a thread of the original cloth in it, and a rudder pintle to be tinkered with. I counted fifty-six patches in our mainsail, although its area was not more than six square yards.

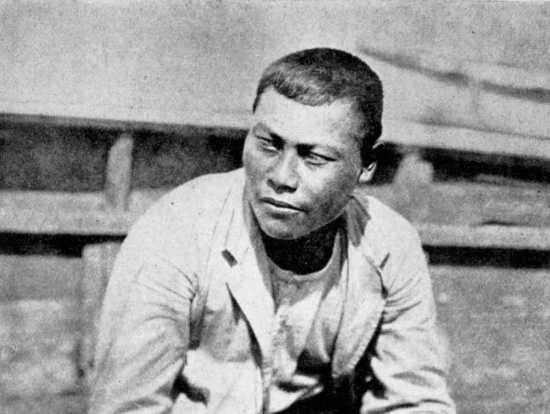

Black Carib boy at Owia Bay. his catamaran is taxed at three pence per foot.

"There is still a satisfying amount of Indian blood left in these people."

When we dragged the three boats down to the edge of the water the sun was just crawling up through the fringe of horizon clouds. The surf was not running so high as on the day before, and yet I could see that we should have to use care in launching the canoes. We dragged the first boat down till its bow was in the foam and with the crew seated at their oars we waited. There was a lull and as a wave broke smaller than the rest we launched the boat on its outgoing tide. The men caught the water and lifted their boat clear of the surf line as a sea curled and broke under their stern. We got off the beach with equal success. Contrary to the lucky rule of three the last boat was swamped and had to try over again.

Once off shore, we stopped rowing and stepped our rig, which consisted of two masts with sprit sails, one smaller than the other, the smaller sail being stepped forward so that we looked like a Mackinaw rig reversed. While these boats have no keel or centerboard, they somehow manage to hang onto the wind fairly well due to their depth of hold. They cannot, of course, beat to any purpose, still they can manage to sail about seven points off the wind which is good enough in the Carib waters where there is always a shore to leeward. With free sheets we ran for a bank to the southeastward where the "black fin" abounds and here we took down our sails and proceeded to fish. The other boats ran to similar banks to the south of us.

The black fin is a small fish, about the size of a large perch, its scales etched in a delicate red against a white skin. The name comes from a black spot at the hinge of the pectoral fin. Instead of anchoring, the two bow men rowed slowly while the rest of us fished. In this way we could skirt the edge of the reef till we found good fishing and then follow the school as it drifted with the tide while feeding.

We used the ordinary hand line, weighted with a stone about the size of one's fist. Above the stone, a gang of from four to six small hooks is baited with pieces of this same black fin. Like bulling this too is deep-water fishing for we lowered fully two hundred feet of line before the stone reached bottom. The line is then pulled up a few feet and held there to await the nibble of the fish. As soon as a bite is felt (one must develop a delicate touch to feel the nibble of a one pound fish at the end of a weighted line two hundred feet long), the line is given a lightning yank and pulled in as fast as possible. Hand over hand, as quickly as one forearm can pass the other, the line is hauled in over the gunwale while it saws its way into the wood.

Sometimes there are two or even three fish on the end of the line when it is hauled into the canoe. I managed, however, to reduce the average considerably at first for I usually found that I had lost both fish and bait. Finally to the joy of Batiste, who considered me his protégé, I began to bring in my share. In the middle of the day we ate our scanty luncheon and then took to hauling in black fins again.

Early in the afternoon a fierce squall came down, dragging half a square mile of breaking seas with it. The Indians began to undress and I did the same, folding my shirt and trousers and stowing them in one of my oiled bags, much to the admiration of the others. We got overboard just as the squall struck and I slipped into the water between Batiste and one Rabat -- they were used to fighting sharks in the water. With three of us on one side and two on the other, we held the boat, bow on to the seas, depressing the stern to help the bow take the larger combers and then easing up as the foam swept over our heads. In a jiffy the squall was past, like a small hurricane, and as we crawled into the boat again I watched it race up the mountain slopes and sweep the mists off the Souffrière. In the break that followed, the top of the volcano was exposed for a few minutes, my second and last view of the crater.

We again pulled up black fins till the fish covered the bottom of the canoe and we ran for home toward the end of the afternoon.

I now found out why the puttering of preparation was done in the morning. No sane man would do more than the absolutely necessary work of dragging his boat under the shade of the thatched roof and seeing that his gear was stowed under the roof poles in the heat of that beach. We made all haste for the cliff road and were soon in the breezy shade of our village grove. My share of the black fins went to the old sea egg doctor who selected one of the largest and fried it for me with all sorts of queer herbs and peppers. This with tanniers, tea, and cassava cakes made my supper. It was an easy existence, this with the Caribs, for I did but little cooking. I merely had to indicate what I wanted and some one or other would start a coalpot before my tent and the meal was soon cooking.

I have hinted at the flexibility of the Indian's language and that night I found a similar flexibility in savage custom. No doubt these Caribs had quickly lost most of their ancient rites and customs with the advance of civilization. I found that in like manner they easily adopted new customs, one of them being the "wake." In the day's fishing I had caught fully thirty black fins and had hauled in my line half again as many times, say forty-five. Forty-five times two hundred means nine thousand feet of line hauled in hand over hand as quickly as possible. This kind of fishing was exercise and I was tired. I went to bed early, but I slept not. It was that truly heathen rite, the "wake," which I believe comes from the Emerald Isle. May all Hibernian priests in the West Indies take note -- it is the savage side of their religion that takes its hold upon the negro and the Indian. May these same Hibernians know that it was simply the "wake" that the Indians took from their faith for they are in religion Anglicans. Adapted would have been a better word for the wake of the Caribs is a combination of what we know as wake and the similar African custom called saracca. A tremendous feast of rice, peas, chickens, and any other food that may be at hand is cooked for the spirits who come in the night and eat. But the poor spirits are not left to enjoy this repast in peace for the living sit around the food with lighted candles and song. In the morning the food is gone and usually there is evidence that spirits have entered into the stomachs if not the ceremony of the mourners.

There is one pleasing feature in this mourning ceremony ; while it is usually begun with a truly sorrowful mien it often ends with all concerned in a happier mood to take up their worldly burdens again. The Caribs of Point Espagñol were content merely with singing. When one of their number dies they pray on the third night after death and on the ninth they sing during the entire night. This happened to be the ninth. In the evening, then, they all assembled in one of the larger huts, not far from my tent.

At first I thought it was only a sort of prayer meeting and I managed to doze off with a familiar hymn ringing in my ears. They would sing one hymn till their interest in the tune began to flag and their voices lower. Then they would attack another hymn with renewed vigor. At each attack I would awaken and could only doze off again when the process of vocal mastication was nearly completed. They were still singing when the sun rose.

Sunday came, as it always should, a beautiful day and I lay on my blankets till the sun was well above the horizon, watching my breakfast cook on the coalpot as a lazy, well-fed dog lies in his kennel meditating a bone. There seemed to be more than the usual morning bustle in the huts behind me and I found that the whole village was preparing to go to church. I must go with them, so I took off my shirt, washed it, and hung it up to dry. Then I carefully washed my face in warm water and proceeded to shave, using the scalpel from my instrument case for a razor. The polished inside cover of my watch made a very good mirror. A varnish brush, if it be carefully washed out with soap and hot water immediately after it has been used will be just as soft and clean as when new. I had such a brush which I used for painting and varnishing the Yakaboo, -- it was not a bad distributor of lather It is remarkable how a shave will bolster one's self respect ; I actually walked straighter afterwards. I donned the trousers that I had washed in the shower bath in Kingstown and with my clean shirt, which had quickly dried in the sun and wind, I made a fairly decent appearance -- that is, in comparison with my usual dress. A clean bandana handkerchief completed the toilet.

With church-going came the insufferable torture of shoes -- that is, for the aristocrats who owned them. My own I was saving for climbs like the Souffrière and I used moccasins. Shoes, however, are the correct things to wear in these parts at weddings, funerals, and church. Aside from these occasions they are never worn.

The exodus began a little after ten o'clock and in five minutes there was not a soul left in the village. The goodly piece of road to Owia was, I thought, a measure in a certain way of the faith of these people. One is apt to be biased in their favor but still I cannot think that it was merely a desire for a bit of diversion to break the monotony of their lives that they all went to church as they did on this Sunday.

I believed as I walked with them that they were obeying a true call to worship. The call to worship became a tangible one as soon as we had circumvented the ravine and were on the road to Owia. It was the clang of a bell, incessant and regular -- irritating to me -- not a call but a command -- the Sunday morning chore of a negro sexton. The church proper had been destroyed by the earthquakes attendant upon the eruption of the Souffrière -- the ruins being another mute piece of evidence of the former splendor of these islands, for it had been built of grey stone and granite brought from overseas, a small copy of an English country church.

The bell was rescued after the earthquake from the pile of debris which had once been its home and mounted where it now hangs, on a cross piece between two uprights. On Sunday mornings the sexton places a ladder against this gallows and climbs up where he pounds the bell as if with every stroke he would drive some lagging Christian to worship. Sheep-like, we obeyed its call till the last of our flock was in the schoolhouse, where the service is held -- when the clanging ceased.

The Carib boy of St. George's who had been brought to Grenada after the eruption of the Soufrière.

The congregation was part negro, but we Indians sat on our own side of the building, where we could look out of the windows, across the little patches of cultivation to the blue Atlantic. We were as much out of doors as in, where, in truth, we are apt to find the greater part of our religion -- if we look for it.

When I said schoolhouse, I meant a frame shed, about thirty feet by fifty, with unpainted benches for the pupils and a deal table at the far end for the schoolmaster. Letters of the alphabet and numerals wandered about on the unpainted walls and shutters in chalky array like warring tribes on tapestry, doing their utmost to make a lasting impression in the little brown and ebony heads of the school children.

The service was Anglican, read by a negro reader, for the parson is stationed in Georgetown and makes his visit only once a month. We shall let him pass in favor of the woman who led the choir. I knew her as she arose ; I had seen that expression from my earliest days, the adamant Christian whom one finds the world over in any congregation. This woman s voice was as metallic as the bell outside and in her whole manner and bearing was that zeal which expresses the most selfish one of us all, the Christian more by force of will than by meekness of heart. She sang. The choir and the miserable congregation merely kept up a feeble murmur of accompaniment.

I said miserable, for did we not feel that there was no chance for God to hear our weak voices above that clarion clang? Between hymns my mind was free to wander out through the windows, where it found peace and rest.

The offending shoes had come off after the first hymn and now furtive movements here and there proclaimed the resuming of that civilized instrument of torture. The last hymn was about to be sung.

After the heat of the day I wandered back to the village alone. My old sea egg woman was sitting on the grassy slope just below my tent and I took up my notebook and sat down beside her. She was in a reminiscent mood and I soon got her to talk about her natal language. She and two other old women were the only ones who knew the Caribbean tongue in this village -- there was an equal number in the other village. When these old people go, with them will go the living tongue of the native of the Antilles -- the words that Columbus heard when he discovered these islands. She was intensely pleased at the interest I showed in her language and I had no trouble in getting her to talk.

Yellow Caribs at Point Espagnol.

Most of the words were unchanged from the time of Bryan Edwards in 1790, when the conquest of the Arawaks must have been more or less complete. Some words such an Sun -- Vehu, now Wey-u ; fire -- what-hò, now wah-tuh -- were merely softened. Other words showed a slight change such as water -- tona, now doonab ; fish -- otò, now oodu. There were some words that had been changed completely, such as moon -- mòné, now haat or há tí.

Most interesting perhaps to the lay mind are the onomatopoetic words that seem to take their meaning from their sound. A word common to many savage languages all over the world was Wèh-wey for tree, suggesting the waving of the tree's branches, he-wey for snake (pronounced with a soft breath), suggesting the noise of the snake in dry grass, and àh-túgah to chop. I watched her wrinkled old face with its far off look and could see the memory of a word come to the surface and the feeling of satisfaction that came into her mind as she recalled the language of her youth.

I sat there with my notebook open and after I had covered three or four pages I went back to words here and there to test her accuracy -- I found that she really knew and was not trying to please. There were some words that would be good for successors to the Yakaboo -- Mahouretch -- Man o' War Bird ; Hourali -- surf ; and Toulouma -- pretty girl. At last she turned to me and said, "Ruh bai dahfedi?" -- "Give me a penny?" -- whereupon I produced a shilling. Her joy knew no bounds ; it would keep her in tobacco for a month.

That night we gathered in one of the huts and swapped yarns to the best of our abilities. I had been with the Caribs for some days and yet there was no hint at that familiarity that would be apt to come with a similar visit to a similar settlement of the natives of these islands. One is very apt to idealize in regard to the Indian, but I can say with absolute certainty that these people lived clean lives and kept themselves and their huts clean.

The huts were all of about the same size, approximately twelve by fifteen feet, of one story, and divided by a partition into two rooms with a door between, each room having a door opening outside. One of the rooms was for sleeping solely, while the other was both a sleeping and living room. While at first the houses seem very small, it must be remembered that the cooking was all done in separate ajoupas, and that most of the time these people live out of doors. They merely use their houses at night for sleeping purposes and as a shelter from rain.

The beds were for the most part rough wooden settees, some with a tick filled with grass and leaves for a mattress. The floors were usually the native soil, tamped hard by the pressure of countless bare feet. A few of the more prosperous families had wooden floors in their huts. The walls were of wattles, woven and plastered with a clay that resembled cement, and the roofs were thatched with Guinea grass. There were usually two small square windows for each room. An attempt was made to conceal the bareness of the walls inside by covering them with old newspapers plastered on like wall paper.

It was in such a newspapered room that we sat and smoked -- that is, as many of us as could comfortably squeeze on the settee or squat on haunches on the floor, the overflow crowding about the open door. In this particular room there was one decoration, a pièce de resistance that brought the hut and its owner to even a higher level of grandeur than newspapered wall or floor of American lumber. It hung from the central beam just above headroom and yet low enough so that one might reach up and reverentially touch its smooth surface.

From the darkened look of the inner surface I could see that it was a burned-out sixteen candlepower electric light bulb. When far out to sea in his canoe, the owner had one day picked it up thinking that it was some sort of bottle. When he saw the trembling filament inside and could find no cork or opening he knew that it was for no utilitarian purpose and must be a valuable piece of bric-a-brac. It had probably been thrown overboard from some steamer passing to windward bound for Barbados.

Did I know what it was? Our conversation hung on it for a long time. Yes, I knew, but to make them understand it was a source of light -- that was the trouble. Sometimes it is disastrous to know too much. I explained it as simply as I could and the Caribs nodded their heads, but there was a doubt in their eyes that was not to be mistaken. The fact that the tiny black thread inside that globe should be the source of light equal to sixteen candles was utterly beyond their comprehension.

I was turning over the leaves of my portfolio when a photograph of my sister dropped out. The old doctor picked it up and as she passed it to me her eyes fell upon it. She gave a start. Might she look at it closely, she asked? It was one of those ultra modern prints, on a rough mat paper, shadowy and sketchy, showing depth and life. The Caribs all crowded around to look. Such a natural picture they had never seen before. When the old woman at last gave it to me she said of my sister who was looking right at us, "We see she, she no see we," which struck me as a bit uncanny.

I was loafing through my last afternoon in the village. Wandering around the huts in the grove, I stopped at an ajoupa, where one of the women was baking something on the hot surface of a sheet of iron. It somehow reminded me of the thin pancake bread that the people of Cairo bake on the surface of a kettle upturned over a hot dung fire. I sat down to watch her bake and lit my pipe. I was a queer man, she said, to sit down in this humble ajoupa just to watch her bake cassava cakes. "No Englis do dat," she added. I had, of course, eaten the cassava before and on my way up through the Grenadines I had seen the negro women raking the coarse flour back and forth in a shallow dish over a bed of hot coals, but I waited till I was in the Carib country before I should see the mysteries, if there were any, of the making of cassava cakes.

The cassava is a root, Manihot utilissima, which grows very much like our potato and may weigh as much as twenty-five or thirty pounds. Ordinarily, it is dug up when it is about the size of a large beet. In the raw state it is highly poisonous, the juice containing hydrocyanic acid. The root is cleaned by scraping it with a knife, then it is sliced and grated. The grating is done on a board with pieces of tin nailed to it. The tin has previously been perforated so that the upper surface is roughened like the outside of a nutmeg grater. This coarse flour is then heated over a hot charcoal fire. In this way the hydrocyanic acid is dissipated by the heat -- a sort of wooden hoe or rake being used to keep the flour from burning.

The woman in the ajoupa had built a hot fire between three stones on which was placed a flat iron plate about two feet in diameter. In the old days a flat stone was used. She prepared the flour by adding just enough water to make it slightly moist. On the hot plate she laid a circular iron band about eighteen inches in diameter -- the hoop off some old water cask and inside this she spread the cassava meal to the thickness of a quarter of an inch. She then removed the hoop and levelled the cassava with the straight edge of a flat stick.

The cake baked very quickly and when it was done enough to hang together she turned it with a flat wooden paddle three inches wide in the blade and about eighteen inches long. As soon as a cake was done she carried it outside and hung it to cool and dry on a light pole supported by two forked uprights. From a distance the cassava cakes looked like a lot of large doilies drying in the sun.

In the evening, when Batiste came from his fishing, I told him that I was ready to go back to Château Belaire. There may have been much more for me to observe among these people -- the life was easy and I had never before had a more fascinating view from the door of my tent. But there was the call of the channel, I must have my try at it and it had been many days since I had sailed the Yakaboo. So we had our last palaver that evening around the glow of the coalpot and the gommier flambeau.

The old wrinkled sea egg doctor insisted upon hovering over my coalpot the next morning, while I broke camp and packed my duffle. Her presence had given my parting food a genuine Carib blessing. By sunup I bade them all good-bye and with Batiste and his men before me -- my house and its goods balanced on their heads -- I left the village. At a sharp bend, where the road curves in by "Bloody Bridge," I turned and had my last peep at the Carib huts.