Alone in the Caribbean

CHAPTER XIII.

SABA.

TO LAND at Saba in a small boat you must choose the right kind of weather. If there is no wind you cannot sail, if there is too much wind you cannot land, for the seas swinging around the island will raise a surf on the rocky beaches that will make a quick end of your boat. For a week there had been too much wind. One day the trade eased up a bit and de Geneste said, "You better make a troy in de mornin'." I made ready.

The next morning seemed to promise the same kind of day as that on which I rushed from Guadeloupe to Montserrat and I feared trouble when I should reach Saba. The wind was already blowing a good sailing breeze and we took to the water at seven o'clock and with Saba a little north of WNW and the wind nearly east I sailed west for an hour wing-and-wing. Then I laid my course for the island. Half an hour later I was obliged to reef because we were making too much speed in the breaking seas. "A fine layout this!" I thought, for if I did not reach the island before the surf ran heavy, I had visions of joining my long painter to all my halyards, sheets, and spare line and swimming ashore with it to let the canoe tail off in the wind, moored to some out-jutting rock or perhaps lying off under the lee of the island for a day or two till the seas calmed. It was all unnecessary worry. The direct distance from island to island was only sixteen miles and was across before the seas had grown too large.

Saba one might call the Pico of the West Indies ; not as high by half, but the comparison may stand for all that. From a diameter of two miles she rises to a height of nearly three thousand feet, her summit lost in the low-lying trade clouds which tend to accentuate the loftiness of this old ocean volcano. The West Indies pilot book gives three landing places and of these I was told by de Geneste to try the south side or Fort Landing, four cables eastward of Ladder Point.

I knew the place when I sailed in toward the island for there was a little shack perched about fifty feet above the beach where the revenue officers, they are called brigadiers, sought shelter from the sun's heat. Above the surf a fishing boat lay on rollers across the rocks, for here is no sand. To the westward, like a terrace, under Ladder Point was a levelled cobble beach some twelve feet above the water where they used to build sloops and schooners before they found that they could get them better and cheaper from Gloucester. Winding upward in a ravine-like cleft were flights of steps hewn out of the solid rock and connected by stretches of steep pathways.

The shack and the pathway up the ravine were the only signs of human habitation and from the barren aspect of the island with its low scrubby vegetation one would not suspect that the steps and paths led to the homes of some three thousand people. When I had made my rig snug and hoisted my centerboard I rowed as close to shore as I dared. As at Statia, a number of black watermen waded out into the sea to lift the canoe clear of the rocks. I rowed a bit to windward to counteract a strong current and then as we swept down toward the men, I jumped overboard and swimming with my hands on the stern of the Yakaboo I waited till we were opposite the men and then shoved the canoe into their arms.

One of the brutes might have taken her weight on his head for my food bags were flat and my outfit thinned out, and for the crowd of them she was a mere toy which they lifted clear of the surf and carried ashore to a couple of rollers without even grazing a stone. The skipper, having a proper regard for his bones, washed himself ashore like a limp octopus.

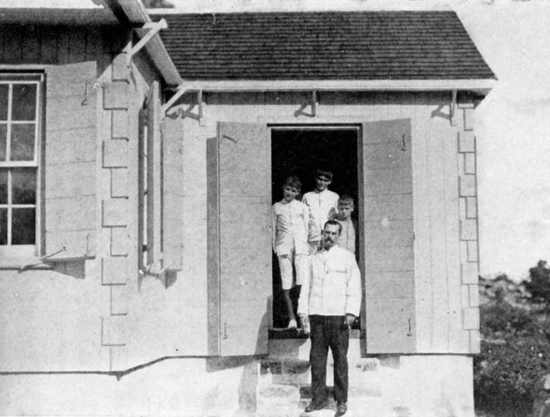

At the head of the Fort Ladder.

"Here Freddie Simmons teaches embryo sailor-men, still in their knee trousers, the use of the sextant and chronometer."

Now there was one person whom I came to know in Statia but whom I have not mentioned as yet because our friendship really belonged to Saba and it was here she was buried only a few weeks after I left the island. She was a kindly elderly woman and a good friend to me. She had been head nurse at the Government Hospital at Antigua and had been under the care of the Doctor at Statia for some time. He suspected cancer, he told me (she told me that she knew it was cancer), and since he could do nothing for her, he advised her to go to Saba to live up in the air where no breeze hung about long enough to lose its freshness and where the chill of night brought with it sound sleep. She had gone on to Saba a few days after my arrival at Oranjetown. One afternoon when I had been complaining of dizziness and nausea the Doctor gave me a kindly shaking and said, "Now see here! you yellow-headed Scandihoovian, you've had just a little too much of old Sol and we've made a little plan for you, Mrs. Robertson and I. When you get to Saba, you'll forget your 'little green tent' for a time and you'll stay with Mrs. Robertson till you're straightened out. Do you mind!" The Doctor could be a bit fierce upon occasion and he was a strong man who would knock you down as soon as not if he thought he could right matters by force.

So when I picked myself up from the wet rocks and followed the Yakaboo up the beach I was accosted by a white man, one Freddie Simmons -- they are for the most part Simmons or Hassels here and you can't go far wrong in calling them by one or the other name.

He was a young man, seafaring evidently, not from any traditional roughness, but from an indefinable ease of gait, scarcely a roll, and from a way of taking in everything as he looked about him as though he were used to scanning the deck of a vessel. He had an open pleasant face that spoke kindly before he opened his mouth and mild blue eyes that could not lie.

"My name is Simmons -- they call me Freddie Simmons." He pronounced it almost like "Fraddie.""I'm a Freddie too," I answered as we shook hands.

"So Mrs. Robertson said. She's breakfast waiting for you up at Bottom -- I'll carry you there just now."

"How the devil did she know I was coming to-day?" I asked. Then he told me how a man up in St. John's had almost looked his eyes out for a week watching for me and was at last rewarded by the sight of a queer rig that could be no other than that of "de mon in de boat."

"But I'll have to stow my canoe somewhere before we start," I told him.

"Oh, we'll take the canoe along," at which he nodded to four black giants who lifted the Yakaboo and started for the path -- two with grass pads on their heads where she rested bow and stern while the others walked at each side like honorary pall-bearers to steady the load. And so we proceeded on our way, eight hundred feet up, to the bed of an old crater where the town of Bottom lies, out of sight of all who pass unless they travel in aeroplanes.

Now I am going to take advantage of the fact that you are soft and short-winded and not used to climbing flights of stairs and steep paths. While you can do little but puff and perspire I shall tell you a little of this strange island. What ancient documents Saba may have possessed were whisked up and blown out across the wide seas over a century ago when a hurricane swept the island in 1787 and took with it almost every vestige of human habitation except the low-set concrete covered rain tanks and the tombs of the ancestors of the present inhabitants. For nearly a century after the island was sighted by Columbus probably no European picked his way up the cleft to the upper bowls of the island. There may have been Caribs living here but I have seen no mention of them. When the Dutch began active trading operations in the West Indies in the early part of the 17th century we find them (the Dutch) already settled in Statia and Saba. For nearly three-quarters of a century the island lived in peace.

In 1665, seventy English buccaneers from the company of Lieutenant-Colonel Morgan who had captured Statia, sailed over to Saba and captured the island with little or no resistance. The main expedition returned to Jamaica but a small garrison was left on each of the islands. Most of the Dutch inhabitants were sent to St. Martin's whither they returned later to Statia. It is from this small handful of English buccaneers that were left in Saba in 1665 by Morgan, that the present white population has descended and while Saba has almost continuously belonged to the Dutch except for a short break in 1665 and in 1781 and also about 1801 it has been truly said that here the Dutch rule the English. There has been little marriage outside of the island by these English people and no mixing with the negroes. Saba is the only island in the West Indies where the whites predominate and the proportion to the blacks is two to one. But the greatest paradox of all is to see here in the heights of this island, six degrees within the tropics, the fair skins and rosy cheeks whose bloom originated in old England in the reign of Charles the Second and has kept itself pure and untarnished there two and a half centuries.

By this time you have clutched my arm and stopped in the pathway long enough to catch your breath and ask, "Yes, but what do these two thousand whites and one thousand negroes live on?" There is little gardening and for the most part the men of the island go to sea where they earn money to support their families and keep their tidy little homes shipshape and neatly painted. As I sit and write this, now that I know the island, I can think of no truer description than that given by the Abbé Raynal in 1798. "This is a steep rock, on the summit of which is a little ground, very proper for gardening. Frequent rains which do not lie any time on the soil, give growth to plants of an exquisite flavor, and cabbages of an extraordinary size. Fifty European families, with about one hundred and fifty slaves, here raise cotton, spin it, make stockings of it, and sell them to other colonies for as much as ten crowns (six dollars) a pair. Throughout America there is no blood so pure as that of Saba ; the women there preserve a freshness of complexion, which is not to be found in any other of the Caribbee islands."

The porters, before us, halted and the Yakaboo came to an aerial anchorage at the crest of the path where the mountainside seemed broken down. It was in reality a "V" blown out of the side of an old crater. No wonder the Yakaboo had come to a stop. She may have seen things unusual for a canoe but she had by no means lost her youthful interest -- she was not blasé. There, before her, spread out on the floor of an ancient crater, was the prettiest village imaginable. Cozy little homes, a New England village minus chimneys, all seemingly freshly painted white with green shutters and red roofs. To guard against the "frequent rains which do not lie any time on the soil" the streets were lined with walls, shoulder high, which were in reality dikes to direct the torrents which are suddenly poured into Bottom Town from the slopes which surround it. A remarkable coincidence that here, high up in the air, the colony should use the dikes of its mother country but for an entirely different reason. What struck me most forcibly was that while there was no hint of monotony the houses gave the outward appearance of a uniform degree of prosperity ; here must be a true democracy ; If any man had more money than his neighbor he did not show it, yet there was no hint of greasy socialism, all of which I found true as I came to know the island.

The "dikes" of Bottom Town.

The Bottom, as the crater floor is called, is a circular plain about half a mile in diameter and surrounded on all sides by a steep wall, continuous except where we stood at the top of the path from the South Landing which we had just climbed and at another point on the west side where the rim is broken and the path called the Ladder descends to the West Landing. Up the rim on the eastern side a path zigzagged and disappeared through a notch in the outline to the Windward Side, the village I had seen from the steamer four months before. Lost in the mist, the summit of the island towered over Bottom to the northward.

Here was a town walled in by Nature. The cleft into which the path was built ended in a small ravine that broke into the level plain of the Bottom and it was across this ravine that Freddie Simmons pointed out the ultimate anchorage of the Yakaboo and the asylum of her skipper. Our procession started again -- we stopped once or twice to meet a Simmons or a Hassel -- to make a starboard tack along the western side of the ravine, a short tack to port, and we put the canoe down on the after deck -- I should say the back porch -- of a cool airy house where we were to keep in the shade for a matter of ten days.

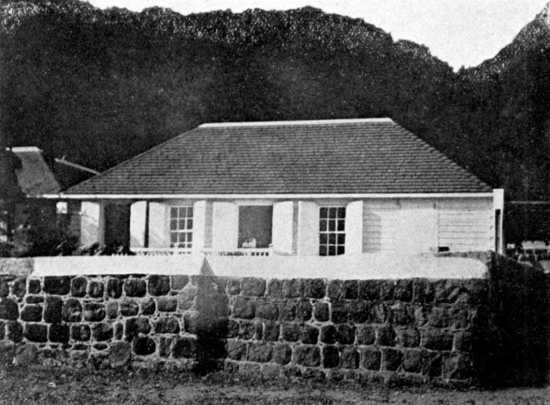

A cozy Saba home.

Here then was the end of my cruise in the Lesser Antilles. I had swung through the arc from Grenada to Saba and in the doing of it had sailed some six hundred miles. My destination was the Virgins and their nearest island lay a hundred and ten miles away. "Oh!" I thought, as I looked down at the canoe, "if I could only be sure that I could make you stay absolutely tight and be reasonably sure of the wind, I would not hesitate to make the run in you." Even if I did get her tight and encountered a calm I knew that I would have little chance of withstanding the heat. Mrs. Robertson had come out to welcome me and I heard her step behind me. She had guessed my thoughts for as I turned she said, "You had better not think of it." At that Freddie put in his oar. "Be content, my boy ; the boat could do it, but one day of no wind at this time of the year would finish you and you don't want to be found a babbling idiot with the gulls waiting to pick out your eyes."

Sense was fighting desperately with the spirit of adventure but at last sense won out -- perhaps through some secret understanding with cowardice.

"Yes, I believe you're right -- I'll let some other damn fool try it if he likes," and that ended the matter.It is in the evenings that one comes to know the people of Saba. They go quietly about their business during the hours of daylight and then, after supper, for hey always eat in their own homes, they meet some place -- it was at Mrs. Robertson's that first night -- to thresh out the small happenings of the day. News from the outside world may have come by sloop or schooner from St. Kitts or Curaçao. Then when the gossip begins to lag, a fiddle will mysteriously appear and an accordion will be dragged from under a chair while the room is cleared for the "Marengo" or a paseo from Trinidad.

I could have no better chance to observe the "rosy cheeks of Saba," and to me the delight of the evening was to be once more among people who lacked that apathetic drift of the West Indies which seems to hold them in perpetual stagnation. The women danced together for the most part to make up for the lack of other men. From the very first, these people have been seafaring and the few men on the island are those crippled by rheumatism or too old to go to sea. You will find Saba men all over the West Indies, captains and mates and crews of small trading schooners in which they are part owners or shareholders. They have learned the trick of spending less than they earn.

Once in a conversation with the port officer of Mayaguez, at the mention of Saba men, he told me that their shore spree consisted in walking to the playa where hey would indulge in ice cream and Porto Rican cigars. On one occasion a Saba foremast hand sought his advice in regard to investing money in a certain coconut plantation in Porto Rico. That they are good sailormen does not rest on mere fanciful sentimentalism for they have been brought up to it from their very boyhood.

In a little house, on the north side of the ravine which the Yakaboo had doubled in the forenoon, was a nautical school provided by a wise government. Here Freddie Simmons teaches embryo sailor-men, while still in their knee trousers, the use of the sextant and chronometer and the mathematics that go therewith. To me, Saba is a memory of living in a bowl over which the sun swung in a shortened arc. Here in Bottom Town the day was clipped by a lengthy dawn and a twilight. As the sun neared the rim to the westward, I used to stroll to the "gap" at the Ladder Landing to enjoy the cool of the late afternoon and watch the ''evening set'' from the shadows of the rocks. Behind me was twilight ; on the rocks below and on the Caribbean before me was yet late afternoon.

Here was a place for a dream and a pipe of tobacco. I used to wonder how near Columbus had passed on his way to Hispaniola. Why did he give her the name of Saba? Was it from the Queen of Sheba or St. Sabar? And then when the sun had finally gone down behind his cloud fringe and the short twilight had been swept out by night, I would turn back into the dark bowl with its spots of square yellow lights from the windows of the Saba people. The stars seemed close here as though we had been pushed up to them from the earth. Later the moon would appear ghost-like over the southern rim and float through the night to the other side.

One morning Captain Ben's schooner was reported under the lee of the island and that afternoon we carried the Yakaboo down the Ladder and put her aboard. She had gone across Saba. I made my last round of good-byes in Bottom Town and then scrambled down the Ladder in the hot afternoon sun. In half an hour a lazy breeze pushed us out into the Caribbean. Saba stood up bold and green in the strong light, her outline distinct with no cloud cap. Little by little the shadows in the rocks at her feet began to assert themselves, blue-black, while her green foliage became a cloth and lost its brilliancy, blue-green it was -- there was distance between us and the snug island. When the sun went down she was a grey-blue hump between sea and sky.

CHAPTER XIV.

SIR FRANCIS DRAKE'S CHANNEL AND "YAKABOO"

WE AWOKE with the Virgins dead ahead. We were approaching them as Columbus had -- from the eastward. His course must have been more westerly than ours, but had he seen them first in the morning light as I did the effect must have been very nearly the same -- a line of innumerable islets that seemed to bar our way. Herrera says, "Holding on their course, they saw many islands close together, that they seemed not to be numbered, the largest of which he called St. Ursula (Tortola) and the rest the Eleven Thousand Virgins, and then came up with another great one called Borriquen (the name the Indians gave it), but he gave it the name of St. John the Baptist, it is now called St. Juan de Puerto Rico." The largest island to windward he named Virgin Gorda -- the Great Virgin.

I spread my chart of the Virgins on the top of the cabin and tried to pick out the southern chain of islands that with Tortola and St. John's form Sir Francis Drake's Channel. On the chart were various notes in pencil which I had gathered on my way up the Lesser Antilles. On the lower end of Virgin Gorda, or Peniston as it is called, a corruption of Spanish Town, I should find the ruins of an old Spanish copper mine and here was that remarkable strewing of monoliths that, as I brought them close up with my glasses, looked for all the world like a ruined city, more so even than St. Pierre -- and was called Fallen Jerusalem.

Next in line came Ginger with a small dead sea on it, Cooper and Salt Islands where the wreck of the Rhone might be seen through the clear waters if there were not too much breeze. Directly on our course through the Salt Island passage was a little cay marked Dead Chest and called Duchess by the natives. Completing the chain were Peter, and Norman, which might have been the Treasure Island of Stevenson. It was these names, Ginger, Cooper, Dead Chest, Peter, and Norman's that awoke the enthusiasm of Kingsley and from the suggestion of this Dead Chest, Stevenson wrote his famous, "Fifteen men on the Dead Man's chest, Yo-ho-ho, and a bottle of rum!"

It was Thursday, June 22nd, the Coronation Day of George Fifth and Queen Mary when we dropped anchor in the pretty harbor of Road Town in Tortola. How ancient will it all sound should some one read this line a hundred years from now! I put on respectable dress, for I had with me my trunk which had followed by intermittent voyages in sloops, schooners and coasting steamers, and from its hold I pulled out my shore clothes like a robin pulling worms of a dewy morning. Shaved and arrayed, I was taken to meet the Commissioner, Leslie Jarvis, who, like Whitfield Smith, deserves better than he has received.

Christian the Ninth, St. Thomas.

That night as I smoked a parting cigarette with the Commissioner on the verandah of Government House and feasted my eyes on Salt and Cooper and Ginger across the channel in the clear starlight, I told him that I should see a little of Sir Francis Drake's Channel before I finished my cruise at St. Thomas.

"We are starting to-morrow in the Lady Constance for a round of the islands and you had better leave your canoe and come with us.""I'll go with you as far as Virgin Gorda if I may and leave you there." And so was my last bit of cruising in the West Indies planned.

The Lady Constance is a tidy little native built sloop, the best I had seen in all the islands, about eighteen tons, used as a "Government Cruiser" to keep smuggling within reasonable limits and as a means of conveyance for the use of the Commissioner on his tours of inspection. She is also used for carrying mail to St. Thomas, a run of about twenty-seven miles.

"Oh, by the way," said the commissioner, as I was half way down the steps, "we take the two ministers with us -- you won't mind that?""How can I?" I answered. "It's the Government's party and I suppose they are quite harmless."

"Quite," came from the dark shadows of the verandah.

In the morning, at a reasonable time, when everybody had enjoyed his breakfast and settled it with a pipe, we got aboard. The Commissioner was accompanied by all the accouterments of an expedition, guns, rods, a leather case with the official helmet within, and most important of all, innumerable gallons of pineapple syrup, baskets of buns and boxes of aluminum coronation medals for each deserving school child in all the British Virgins. The Yakaboo we put aboard forward of the cabin trunk -- the ministers brought with them their nightgowns and a pleasant air of sanctity.

Somewhere there lurks in my mind a notion to the effect that professional men of religion are among sailors personae non gratae at sea. A thing may in itself be quite harmless and yet may bring down disaster to those about it. Perhaps it is just a whim of the Lord to test his self-proclaimed lieutenants when they venture into the open. There seems always to be trouble at sea when a minister is aboard. The harm we received was trifling but it was a warning. The breeze was fresh when we started and the Lady Constance had already bowed once or twice to the seas when we close-hauled her for the beat up the channel. Suddenly a wave boarded us and with an impish fit gathered the little deck galley in its embrace and with a hiss and a cloud of briny steam carried the box with its coal-pot and cooking dinner and swept the whole of it into the sea. I looked at the Commissioner and we both looked at the parsons. There was a warning in this. Titley, the big colored skipper, felt it too and from that time our sailing was done with great care. So much for superstition, it seems to grow on me the more I have to do with the sea.

The channel was full of fish, Jarvis had told me, and with our towbait we would take at least one fish on each tack. We made a good many tacks and got one small barracuda. Of course we knew where the trouble lay. We spent the night under East End where in the morning the Commissioner landed and put an official touch to the depositing of syrup and buns in sundry little dark interiors and gave out medals for outward adornment. Thus in the outermost capillaries of the United Kingdom was the fact of the coronation brought home, and, most truly is the stomach of the native the beginning and end, the home and the seat of all being. Then we slipped across to Virgin Gorda and a day later were in Gorda Sound, a perfect harbor, large enough, some say, to hold the entire British Navy.

It was from Gorda Sound that I began my little jaunt about the Virgins. I had been looking forward to sailing about in the Drake Channel, for in many ways it is ideal canoe water. Here is an inland sea with a protected beach at every hand, blow high or low. Columbus may have been far off when he named them the "Eleven Thousand," but as I sit here and glance at the chart I can count fifty islands with no difficulty, all in range of forty miles.

The Virgins are mountainous but much lower than the Lesser Antilles and while they are volcanic in origin they do not show it in outline and must be of a much older formation than the lower islands. They are the tail end of the range which forms Cuba, San Domingo, and Porto Rico.

I bade good-bye to the Lady Constance one morning, and sailed out before her through the narrow pass by Mosquito Island, while they took the larger opening for low Anegada, which we could not see, twelve miles to the northeast. I hauled up along the shores of Virgin Gorda and made for West Bay. What a contrast was this sailing to our traveling in the lower islands. Instead of the large capping seas of the trades here was an even floor merely ruffled by a tidy breeze. For a change it was delightful, but too much of it might prove tiresome and in the end we would probably be seeking open water again. I was soon in the bay and running ashore at the western end I dragged the Yakaboo across the hot sands and left her under the shade of the thick sea grapes that form a green backing to the yellow beach. There is no town on Virgin Gorda, merely clusters of native huts that might be called settlements, the two larger having small school houses which are also used as churches.

The life in these small outer cays is of a very simple nature. There are no plantations and the negro lives in a sort of Utopian way by raising a few ground provisions near his hut and when he wishes to change his diet he goes fishing. To obtain cash he sends his fish and ground provisions to the market in Tortola or St. Thomas and strange to say his most urgent need of cash is for the buying of tobacco.

Once, during the hurricane season, it chanced that all the sloops were at St. Thomas when Virgin Gorda found that it had run out of tobacco. The sloops had been gone for a week and were due to return when suspicious weather set in and no one dared leave port even for the shortest run. What with the hand to mouth existence these people lead and the small stock in the shops, there is never more than a week's supply of tobacco on Virgin Gorda and that notwithstanding the fact that the negroes here are inordinate smokers. The first day after the tobacco had given out was lived through with no great difficulty. On the second, however, the absence of the weed began to make itself felt.

The dried leaves of various bushes were tried but with little success. Dried grass and small pieces of bone were burned in pipes and finally those most hard pressed took to pulling the oakum out of the seams of an old boat that lay on the beach of West Bay. When day after day followed and the sloops from St. Thomas did not return, the whole population finally gave itself over to the smoking of oakum and watching for the return of their sloops. Even the oakum in an old beached fishing boat will not furnish smoking material for a couple of hundred natives for any great length of time and finally the island was quite smokeless, a state which to these people borders close onto starvation.

At last the sullen threat of a hurricane passed off and the next day the lookout reported white sail-patches beating up the channel. When the sloops beat into West Bay late that afternoon, the whole population of Virgin Gorda was waiting for them. As soon as the boats were beached the first business of the island was to enjoy a good smoke. To have been there with a camera and to have caught the two hundred columns of bluish smoke drifting aslant in the light easterly breeze!.

In the morning I was again on the summer sea of the channel. We had cleared Virgin Gorda and were lazing along toward Ginger when I saw the mottled fin of a huge devil fish directly on our course. I was in no mind to dispute his way -- not being familiar with the disposition of these large rays -- so I hauled up a bit and let him pass a hundred feet or so to leeward. I stood up and watched him as he went by and swore that some day I would harpoon just such a fellow as that from a whaleboat and take photographs of the doing. Just now I was leaving him alone. His fin, mottled brown and black like the rest of his upper surface, stood nearly three feet high and I judged his size to be about eighteen feet across from tip to tip.

For my nooning, I went ashore on a little beach on Cooper where I built a fire in the shade of beach growths. The sun, it seemed, did not have the deadly spite in its rays as in the lower islands but this may have been wholly surmise on my part. It was a great joy to be able to do a bit of beach work -- that is to live more on the beaches than I had been doing in the Windward and Leeward islands. I sat for a while under the small trees where the cool wind seeped through the shade and set myself to a real sailor's job of a bit of needlework on the mainsail where a batten had worn through its pocket.

There is a peculiar freshness about these small cays that seems to do its utmost to belie any suspicion of a past. The beaches are shining, the sand and pebbles look new and in a sense perhaps they are, for one does not find here the thin slime on the rocks that is an accompaniment of long years of near-by civilization. Man befouls. The vegetation is for the most part new, for excepting an aged silk cotton tree, there are no growths of great age. The palms grow for a generation or two and pass away. The small woody growths of coarse grain and spongy fiber quickly bleach out and rot away upon death. They almost seem to evaporate into the air. Here are places of quickly passing generations that suggest eternal youth. Were our impressions of these places not biased by brilliantly colored pictures which we have seen in our youth of pirates and adventurers of a former age portrayed on brilliant white beaches with a line of azure sea and a touch of fresh green, we would swear that they were no older than a generation. But all these beaches of perpetual youth knew the rough-booted pirates of centuries ago and the Indians before them. Here in the channel between these outer cays and Tortola, three centuries ago, convoys of deeply laden merchant ships under clouds of bellying squaresails used to collect like strange seafowl to sail in the common strength of their own guns and a frigate or two for the European continent. Drake and Morgan and Martin Frobisher, whom we think only as of the Arctic, and the Admiral William Penn knew these places as we know the environs of our own homes.

When I had finished my sewing and had washed my dishes I shoved off again and in a few minutes -- what a toy cruise ! -- I was ashore on the beach of Salt island where a few huts flocked together under the coco-palms. Here I found a native by the name of William Penn. I asked him if he had ever heard of the old Admiral. Penn, he told me, was an old name in these islands, there having been many Williams. In all probability the name was first assumed by the slaves in the old days and then handed down from generation to generation.

It was here, in 1867, that the Royal Mail Steamer Rhone was wrecked in a hurricane. William Penn showed me in one of the huts a gilded mirror which had been "dove up" and he told me that the natives were still diving-up various articles from the wreckage. We put off in our canoes and rowed around to the western shore where the steamer lies in some forty feet of water. She must have been broken up on the rocks during the first onslaught of the hurricane and then blown out to where she now lies about two hundred yards from shore. The conditions were not particularly good, yet we could see what was left of her in large masses of wreckage literally strewn about on the ocean floor.

Then I hoisted sail again and was off across the channel to Dead Man's Chest where I would camp for the night. The surf was too high, however, and I had to content myself with a photograph and to sail on to Peter where I came ashore in the cool of the evening on a sandy turtle beach. A native came out of the bush and without any word on my part immediately turned to and built my evening fire. There was a good deal of the simple coast African in him -- he freely admitted that it was curiosity that brought him to see me and the canoe and in return for a civil word he was only too glad to do what service he could. He showed the same pride of his village (these negroes all have a strong appreciation of the picturesque) that I found all along the lee coasts and he begged that I visit the snug little bay where he lived, when I set sail in the morning.

The night promised clear with a small new moon crescent -- perfect for sleeping without cover. I had no sooner settled myself down in my tiny habitation than the wind began to drop and thousands of mosquitoes came out of the bush on a rampage. Instead of pitching my tent on the ground I ran the peak up on the mainmast which I stepped in the mizzen tube. The middle after-guy I ran to the foot of the mizzen mast which was now in the mainmast tube. The sides I pegged in the sand under the bilges of the canoe and in this way I had a roomy canoe tent which gave access to the forward compartment in case of rain.

After I had rigged the tent I beat the air inside with a towel so that when I fastened down the mosquito bar there was no one inside but myself. I found, however, that I was plenty of company. While the night air outside was cool enough I soon found that the heat from my body accumulated in the tent till I lay on my blankets in a bath of perspiration. A loose flap in the top of the tent would have taken off this warm air as in a tepee. Had there been one mosquito to bother me sleep would have been impossible. At last a gentle night breeze sprang up, I wiped my body dry, and dropped off to sleep.

The next day was July first, the last of the cruise of the Yakaboo, and almost of the skipper. I was up with the sun -- many evil days begin just that way -- and off the beach after a hasty breakfast. My destination was Norman Island -- I would come back to Peter again, where there were caves in which treasure had actually been found and where there was a tree with certain cabalistic marks which were supposed to indicate the presence of buried treasure. I cleared the end of the island and hauled up for Norman, passing close to Pelican Cay. Norman is a long narrow island with an arm that runs westward from its northern shore, forming a deep harbor which gives excellent protection from all quarters but northeast.

In a rocky wall on the extreme western end of the island where the harbor opens out to the channel are two caves which can be easily seen when sailing through the Flanagan passage into Sir Francis Drake's Channel. These caves are the ordinary deep hollows one commonly finds in volcanic rock formation close to the sea and were for years unsuspected of holding hidden treasure. They say that a certain black merchant of St. Thomas, who had literally become rich over night, found his money in the shape of Spanish doubloons from an iron chest which he dug up in the far end of one of the caves. The man had bought Norman, had spent some time there and for no apparent reason had suddenly become rich. One day a curious fisherman found the empty chest by the freshly dug hole in the cave and there were even a few telltale coins that had rolled out of range of the lantern of the man who dug out the treasure. And there must have been another place for one day a small schooner came down from the north and entered at the port of Road Town. She picked up a native from Salt island and one night she ran down to Norman's. The next morning she put the native ashore on his own island and sailed for parts unknown -- as to what happened on Norman the native, it seems, was strangely silent. There's the whole of the tale except what's known by the crew of the schooner.

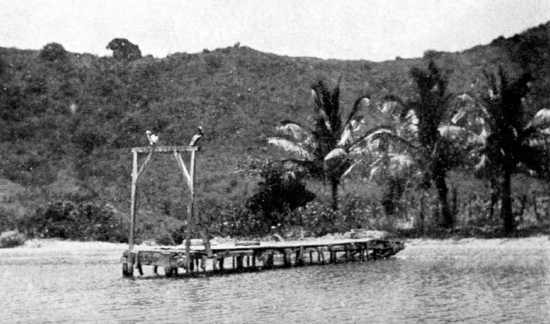

The jetty at Norman's Island.

As I sailed into the harbor, I saw a sandy beach at the far end where a small wooden jetty stood out in the calm water. Fringing the beach was a row of small coco palms, behind which the island bowled up into a sort of amphitheater of scrubby hillside. What a place for a pirate's nest! There is scant printed history of Norman and what is written is for the most part in some such records as led the schooner to the island. I rowed in to the beach, the hill to the eastward cutting off all moving air so that a calm of deathly stillness held the head of the bay in a state of quivering heat waves. The low burr of wind in the upper air outvoiced whatever sound might have come from the surf on the windward side of the island.

There was something peculiarly uncanny about the place which was all the more accentuated by the lonely jetty and a pair of pelicans that launched forth in turn from their perch on the gallows-like frame at its end, to float in large circles over the clear sandy-floored harbor, remounting again in lazy soft-pinioned flaps. They flew off as I tied up to the jetty but completed their circle as I stepped ashore and sat eyeing the Yakaboo as if detailed there on sentry duty. The heat was intolerable and if I were to camp on Norman I should have to find a cooler spot than this.

First, however, I would hunt the pirate tree, but I had not gone far into the bush before I began to feel faint and sick. The bush was close but shaded and as I retraced my steps to the jetty and came out again into the full glare of the beach the heat came upon me like a blow. I needed water and I knew where I could get it, lukewarm, in my can in the after compartment of the canoe. I tried to stoop down from the jetty but nearly fell off so I followed the safer plan of lying down on the burning boards and reaching into the compartment with my arms and head hanging over.

The hatch came off easily enough and with it rose the hot damp odor of the heated compartment mixed with the smell of varnish. I took out a bag or two and found them covered with a sticky fluid. Then I discovered my varnish can lying on its side with its cork blown out, spewing its contents over all my bags. When I lifted my water-can it came up with heartsinking lightness. I took it up on the jetty and sat up to examine it. There in the bottom was a tiny rust hole where the water had run out. Then I lay down again and dabbled my fingers in half an inch of water and varnish in the bottom of the compartment. I had sense enough to know that I was pretty well gone by this time and I went ashore where I lay for some time under the shade of the young coco palms.

If I could only get one of those water-nuts I should feel much better and although the trees were young and the nuts hung low they were still nearly three feet above my reach. Perhaps I could shoot them down, so I went back to the canoe and got the rifle which so far had been of little use to me. The will of the good Lord was with me for I found that I could almost touch the nuts with the muzzle of my rifle. By resting the barrel upward along the trunk of the tree I could poke the muzzle within a few inches of the stems. Any one could have made the shot, but I missed because I forgot that the sight was raised a good half inch from the center of the bore. It took me some time to reason this out and I had to sit down for a while to recover from the shock of the recoil. Then the idea came to me. I aimed the rifle this time with its axis in line with the stem and pulled the trigger. Down came the nut and I blew off its head and drank its cool liquid. In like manner I shot another coconut. Stalking the fruit of a coco palm may sound like the keenest of sport, but no hunting ever gave me keener satisfaction than shooting these two nuts in the neck.

The milk was cool and refreshing and I believe it pulled me out of as tight a corner as I have ever been in alone. There was no one living on the island. The coming on of nausea and the feeling that I did not exactly care what happened was hideous to my better sense and I felt that at all costs I must make an effort to refresh myself and then leave the island as soon as possible. By sheer luck of super caution I got into the canoe and untied the painter (I found it trailing in the water when I got out in the channel later) and then in one last effort of fostered strength I rowed out of the cove into the breeze where I quietly pulled in my oars and lay down.

A little time later the quick roll of the canoe roused me and I found that I was clear of Norman and close upon Flanagan Island. The wind was cool and I made sail for Tortola. I was still very faint but I had held that mainsheet for so many miles that even half insensible I could sail the Yakaboo into Road Harbor -- perhaps she did a little more than her half of the sailing. For three days I was taken care of at Government House and then feeling perfectly well I prepared to sail for St. Thomas. The anxious Commissioner would not hear of this and the doctor forbade me to go into the sun again, warning me to take the next steamer for New York.

On the afternoon of July Fourth I was bundled aboard the Lady Constance, together with the Yakaboo, and in the evening we sailed into the Danish port of Charlotte Amalia.

• • • So here ends the cruise of the Yakaboo after nearly six months of wanderings in the out-of-the-way places of that arc which swings from Grenada to St. Thomas. Six months may seem a long time to you of the office who at the most can get a month of it in the woods or along shore, but to me these months had been so full of varied interest that they were a kaleidoscope of mental pictures and impressions, some of them surprisingly unreal, that I had gone through in weeks. Had it not been for the heat I should have kept on and cruised along Porto Rico, San Domingo, and Cuba, crossing the large channels by steamer if necessary.

But it is the sun which makes impossible the true outdoor life in these islands as we know it in the north. I was content with what I had seen. I did not think back with longing of Norman where I had failed to spend the days I had planned, nor of Diamond Rock off Martinique where I had wished to land, nor of the half-French, half-Dutch St. Martin's that was out of reach to windward, nor of Aves, the center, almost, from which the arc of the Caribbees is swung, for I decided, should the opportunity offer, I would come down here again in a boat large enough to sleep in off shore and in which I could escape the heat of the day at anchor in the cool spots where the down draft of the hills strikes the smooth waters of protected coves.

One morning the Parima nosed her way into the harbor and I put off to her in a bumboat with my trunk and outfit aboard and the Yakaboo towing astern. The trunk and outfit followed me up the companionway and after a talk with the First Officer I rowed the Yakaboo under one of the forward booms which had swung out and lowered its cargo hook like a spider at the end of its thread. I slipped the canvas slings under the canoe's belly and waved for the mate to "take her weight." She hung even and holding on to the hook I yelled to the head and shoulders that stuck out over the rail to "Take her up!"

"'Take her up,' he says," came down to me and we began to rise slowly into the air. We were leaving the Caribbean for the last time together and were swung gently up over the rail and lowered to the deck.

The steward led me to a Stateroom that I was to share with an American engineer returning from Porto Rico. Here was one who did not know of my cruise and I was glad to escape a torrent of questions. He, the engineer, looked askance at my rough clothes and I chuckled to myself while he hung about the open door in the altogether obvious attempt to forestall any sly thieving on my part. I don't blame him. I shaved and packed my suitcase with my shore clothes and then hied me to the shower bath whence I emerged an ordinary person of fairly respectable aspect.

Then some confounded maniac walked along the deck clanging a bell and I knew that it was the call to breakfast. I went below and took my seat opposite the engineer from Porto Rico who recognized me with a start. I embarked on a gastronomic cruise, making my departure from a steep-to grapefruit that had been iced and coming to a temporary anchorage off a small cay of shredded wheat in a sea of milk -- foods of a remote past. I was tacking through an archipelago of bacon and eggs when I heard the exhaust of the steam winch and the grind of the anchor chain as it passed in over the lip of the hawse pipe, link by link. I had cleared the archipelago and was now in the open sea of my first cup of coffee and bound for a flat-topped island of flapjacks when I felt the throb of the propeller slowly turning over to gather the bulk under us into steerage way. Presently the throb settled down to a smooth vibration -- we were under way.

Some one at my right had been murmuring, "Please pass the sugar ? -- may I trouble you for the sugar? -- I BEG your pardon but" -- and I woke up and passed the sugar bowl. Someone else said, "I see by the papers" I was back in civilization again and as far from the Yakaboo and the Lesser Antilles as you, sitting on the back of your neck in a Morris chair.