The

Chinese Sail

by

Brian Platt

Copyright © Anthony Platt 2001

Anthony Platt [ amwplatt@btopenworld.com ] sends along this wonderful article which his late brother Brian Platt wrote about 1960. It was never published in full. This is a thoughtful and lucid essay accompanied by helpful drawings and photos.Because of the many photos the page is slow to load, so be patient. They are reproduced in a large size in hopes of showing details which would otherwise be invisible. The drawings are especially nice. In a few places I have added [something in brackets] where, for example, a different term is in current use. Otherwise only a few sentences have been edited here and there, mainly to eliminate the occasional run-on or lengthy one. It seems as if Brian would have been a fine fellow to sit with and talk over the good and bad points of the Chinese rig.

Anthony has provided Brian's bio:"Following College, Brian joined the Malayan Civil Service in 1952 and was sent to Kuala Lumpur. He was soon given a remote country District to look after and loved the job. But when Independence came in 1957, he opted to take a leaving gratuity which he promptly spent on a boat to take him to Canada where he wanted to live and work.

This first boat, "Chempaka", was a disaster, though he struggled as far as Manila from his starting point, Singapore. Determined to continue, he moved to Hong Kong and had a Chinese junk built. "High Tea " (Cantonese, it seems, for Emperor of the Seas) got him eventually, via Okinawa and Japan, to Eureka, California on Christmas Day 1959 - and then finally San Francisco.

It was a difficult journey with many near disasters along the way, but he and the boat made it in good shape and he became an enthusiastic fan of the junk rig. He also produced a highly readable book Parallel 40 North to Eureka about the two voyages which, for reasons unknown, never appeared during his lifetime (he died in 1989). The book was published posthumously last year by his brother Anthony.

I very much appreciate what you're doing to make sailing people aware of Brian's great achievement. Warmest regards, Anthony."

To purchase a copy of Brian's Parallel 40 North to Eureka, contact Anthony Platt at:

amwplatt@btopenworld.comor by mail:

17 Westgate Street, Bury St Edmunds

Suffolk IP33 1QG, United Kingdom.Anthony says pound sterling or dollar checks are acceptable. Price in USA is US$31.00 by air ("pretty fast, like inside a week") or $26.50 by surface mail ("according to the Post Office, very slow"). Contact him for pricing in other countries.

===

The Chinese Sail

Nobody could have designed the Chinese Sail, if only for fear of being laughed at. A device so elaborate and clumsy in conception yet so simple and handy in operation could only have evolved through trial and error. It is indifference rather than difficulty that has caused Chinese sailing craft to be so little studied in the West but the difficulties themselves are formidable enough.For a start there have probably always been more varieties of sailing craft in China than in all the rest of the world put together. Furthermore:

"the study of everything connected with the Chinese junk is complicated by the most vexatious contradictions. No sooner is an apparent solution found, or a rule permitting of a particular classification arrived at, than along comes an exception of such a formidable nature as to wreck all previous conclusions".So wrote G.R.G. Worcester, formerly of the China Customs. He is one of the very few Europeans to have given the subject some of the attention that it would seem to deserve.

In my small way I found the same difficulty and, for that reason, merely relate what I learnt from "High Tea" and from what I had seen of Hong Kong junks before I set sail. The letters E & OE (errors and omissions excepted) should be read beside any general statement I may make about the way things are arranged aboard Chinese boats.

Another difficulty I met with was the fact that some parts of the Chinese rig have no equivalent in the West. We have no name for them. I have done my best to adapt conventional terms - though some of those may be not too familiar to modern yachtsmen - but where I could find no suitable term I have had to invent my own.

The masts, hull and standing rigging

The Chinese Sail may be defined basically as a fully-battened balanced lugsail. There is one sail to each mast. Other sails may sometimes be rigged on booms or between the masts but a two-masted vessel normally carries two sails, a three-master three sails etc. The sailing junks around Hong Kong generally have two or three masts, not more. The foremast is stepped right in the bows, the mainmast about a third of the way aft. If there is a mizzen the construction of the Chinese rudder generally prevents it from being stepped in the centre line, in which case it is stepped to starboard.A description of the rig is not complete without some description of the hull that carries it: and particularly so with the Chinese junk which is very much an integrated craft. There is no false-keel on Chinese sailing boats. Instead there is a great barn door rudder hoisted in chocks, which when lowered extends well below the level of the keel. To some extent this acts as a centreboard. It can be raised and lowered to adjust the balance when sailing and when beached. When lying head-to-wind under a sea-anchor the whole rudder can be lifted clear of the water. On the Hong Kong styles of junk there is frequently a projecting forefoot where the stem joins the keel, presumably to balance the underwater grip of the rudder. In addition most junks up to about 60 ft overall have a daggerboard between the mainmast and the foremast.

General hull design of

two-masted Hong Kong junk

(no particular style) illustrating fore foot, dagger

plate, rudder and catheads. The dotted lines indicate

some of the watertight bulkheads to show how

they are disposed to distribute the lateral strain of

the

masts and dagger plate.

Inside, the hull is built around a system of watertight compartments. Whereas additional seaworthiness may be a consequence of this type of construction I doubt whether it was ever the object. The Chinese hull (if we are speaking of the seagoing varieties) is a seaworthy shape and in normal circumstances has no need for such aids: and the Chinese boatman, for his part, will rarely spend money on anything which he does not consider strictly necessary. The purpose of the bulkhead construction, I think, is twofold: structural strength and working capacity. Different types of cargo or the consignments of different customers can be isolated from each other in the different holds. On fishing boats some of the compartments are filled with water to keep the bait or catch alive.The large stern of the Chinese junk provides a working and living area, which is frequently extended even further with an overhang. Indeed, if there is a mizzen mast the overhang is essential to stay it and to work the sheets. A couple of catheads which project on either side of the bow are linked by a crosspiece and serve, on Hong Kong junks, another multiple purpose: to stay the foremast, to ship the anchors (whereby I justify the use of the term "cathead") and perhaps also to provide a working platform at the bow.

In general the standing rigging of the junk appears unbelievably flimsy, but in fact the nature of the Chinese sail imposes such an evenly distributed strain that heavy rigging does not seem to be necessary. The big junks of Northern China often carried no standing rigging at all, the masts being strengthened instead with laminating strips clamped on by iron bands. With an unstayed mast the collar where it passes through the deck will act as a fulcrum and the butt of the mast will work on the keel like a crowbar: but the junks of northern China did not even have a keel, merely a thicker plank down the centre to take the mast stepping! The portion of the mast below decks, however, was braced against the system of internal bulkheads. The bulkhead type of construction not only would have made for a rigid frame but must evidently have distributed this leverage in the same way as standing rigging; perhaps more efficiently.

High Tea anchored.

All the masts have a forward rake which, with the high poop, give the vessel the appearance of "slipping downhill". This creates the impression that the junk would bury her bows in a head sea, but I found it to be quite illusory. Some helicopters create the same impression that they are flying into the ground! The reason for the forward rake of the masts is probably to cause the sails to swing outboard in light winds. The rake of the foremast is much more pronounced than that of the others. Acting half as a mast, half as a bowsprit, it increases the sail area and brings the centre of effort forward. Another effect is to cause the foresail to "goosewing" of its own accord when running before the wind.Charles Jarrett said:

"The forward rake of the mast takes any viciousness out of a gybe by making the sail swing uphill: also, if the sail does succeed in gybing, as soon as the after part gets into the lee of the mainsail, the balance part forward of the mast is swinging into the wind, an action which so deadens the motion of the sail that, as a rule, it comes back to its original setting". (Yachting Monthly, 1924)

High Tea Sailing.

The Sail

On Hong Kong junks the sail hangs always to starboard of the mast, though this varies in different parts of China. Sailing to windward the lugsail tends to be more efficient on the tack where it lies away from the mast than when it lies against it, which may explain why in some areas of China the mainsail is hung to one side and the other sails to the other - to give equivalent efficiency on both tacks. Possibly the local preference was conditioned in the first instance by the prevailing winds. In the South China Sea they blow half the year from the northeast and half from the southwest and the fishing junks from Hong Kong would tend to sail East out to sea and West back home, so that when sailing close-hauled they would nearly always be on the port tack: hence the sails are hung to starboard.The battens (A-B in Diagram 1) are rigid lengths of bamboo with very little taper or flexibility. They are attached to the port side of the sail to take most of the chafe against the mast when on the starboard tack. On the starboard side, sandwiching the sail to the batten, there is usually a thin slat of bamboo (i.e. instead of the batten being held in a pocket as in Western rigs the battens are on the outside and the sail is held between them). The slat prevents the sail from bellying between its points of attachment to the battens and also acts as a chafing strip when the sail rubs against the shrouds.

On the port side of each batten there is a parrel (C) around the mast which holds the sail against the mast when on the port tack. Insofar as there is a "boom" at all on the Chinese sail it is not the lowest batten but the one above it. The distance between the true lowermost battens is only about half that between the others and in any case that portion of the sail is usually brailed up to enable the helmsman to see underneath. Even when the sail is fully extended the lowest panel seems to do hardly any work. It has no parrel to hold it against the mast at its forward end and sometimes no sheet at its after end, so that on the port tack it hangs loosely to leeward. That portion of the sail might be described as an appendix: the real foot of the sail being at the lowest batten but one, which I will call the "boom".To the forward end of the boom there is an inhaul (D) by which the distance of the tack forward of the mast can be adjusted [often called the boom parrel]. The sail's centre of gravity, suspended from the halliard, is of course well aft of the mast and the weight of each batten tends to push forward. If unchecked the luff of the sail would be a convex line and there would be a transverse strain on the sailcloth between each batten. To control this a line or wire (E) runs from the forward end of each batten to about the centre of the batten below it. The weight of each batten hangs downward and forward and the lines at "E" (which I term "checks") opposed the forward thrust of the higher batten to the downward thrust of the lower.

Aboard High Tea I found that the checking action was not complete and there was still some convex line to the luff; not only pulling the sail out of shape (as the luff had been cut to fall straight) but causing the forward end of the battens sometimes to foul the shrouds. To control this tendency, I evolved a luff-line as illustrated in Diagram 2.

It worked very effectively and I thought I had made a real contribution to the Chinese rig until I discovered later that some North Chinese junks have an arrangement of combined parrel and luff-line to serve just that purpose!

|

|

The foot of the sail is carried on two buntlines (F), one forward and one aft of the mast [also called topping lifts or lazyjacks]. |

If it is blowing very hard the wind may belly out the panel in between and prevent the battens from meeting properly. But this is very simply corrected by pulling up the foot of the sail a few inches with the buntline.Whereas the battens are bamboo, the yard of a Chinese sail is wood. It is possible that because the whole weight of the sail is suspended from the halliard at one point bamboo might not be strong enough: or it may be that a heavier spar is wanted along the head to bring the sail down faster. This would particularly apply to the Hong Kong sail and its comparatively short yard.

The arrangements connecting the yard with the mast are shown in Diagram 3. There is one halliard (no peak halliard) and a roving parrel [also called running yard parrel] is led from the same place on the yard as the halliard, passing round the mast, back through a block and down.

When raising or lowering sail it is necessary to adjust this line. Such, at least, was the arrangement as first rigged aboard High Tea. It had the merits common to the Chinese rig of low capital cost and ease of repair, but I found the extra line a nuisance to adjust. I experimented, therefore, with a brass ring and wooden parrel balls that encircled the mast and was shackled to the yard at the point where they crossed (somewhat forward of the halliard). It worked quite efficiently but being hard it tended to chew up the masthead, so I improved on it with a collar made of old fire hose liberally coated with paraffin wax to provide stiffness and lubrication. At either end it was riveted to a metal triangle and a bell shackle passed through the triangles linked it to the yard. It worked very well.

The Sheets

The sheets of a Chinese sail do two things. They control, as ours do, the angle of the sail to the fore-and-aft line of the vessel. They also control the shape and flow of the sail. The two functions are independent: the second being performed by thinner lines, "sheetlets", running from each of the battens to a euphroe connected to the sheet itself.The sheetlets are as far as possible a continuous line (Diagram 4) starting from the top batten. There is no line to the yard and no need for a vang with such an arrangement, as the sheetlets give adequate control up to the top of the sail.

x = ordinary wooden block

with wood or brass sheave;

y = figure-of-eight friction block; z =

euphroes.

This arrangement requires a good deal of space so if the sail is to be close-hauled the sheet needs to be led to the windward side. When going about the sheet must be unhitched from the windward side, the sheetlets flicked around the leech as it comes across so that they do not foul the ends of the battens and the sheet hitched up again to the other side.

I had noticed on the foresails of some junks an arrangement of double sheets and sheetlets: one set on each side of the sail so that on either tack the windward set took up the strain. I reproduced this arrangement on all three of my sails, leading the fore and mizzen sheets aft and forward so I could control them from the cockpit. To discourage the sheetlets from fouling the end of the battens I attached them forward of the leech about 15% of the width of the sail. Going about, thereafter, became simply a matter of pushing the helm down.

The purpose in leading the sheetlets to and fro through the euphroe in a continuous line is to make for easy adjustment. A little familiarity with the lead of the sheetlets makes it very simple to adjust the shape of the sail (e.g. to flatten it when sailing to windward). To permit two further adjustments the lower end of the sheetlet is left free, either attached to the appendix batten or knotted to stop it running out through the euphroe. If the sheetlets become too long the sail cannot be fully close-hauled so by taking in on the lower end of the sheetlet adjustment can be made for stretch and for the lengthening effect when the sail is reefed.

Comparison with Western rigs

Sailing qualities

Comparisons are still being made and merits argued between the gaff and Bermudan (to Americans, "Marconi") rigs. The Bermudan is generally accepted as being superior to windward because of its long leading edge, but for cruising the gaff is sometimes preferred on grounds of a shorter mast and better distribution of sail off the wind. Short of conducting a controlled experiment, with an identical hull under identical conditions, it would be difficult to assess how the Chinese sail compares.I remember once sailing a Dragon to windward in Hong Kong harbour, against a light but steady breeze and watching a medium-sized Chinese junk (50 to 60 ft overall) on the same tack. Lacking a deep keel the junk was making a lot more leeway than I, so his actual course was not so close as mine, but he was pointing as close and sailing as fast as I was. In such conditions, and comparing a work boat with one designed and maintained for racing, the comparison seemed to me to speak pretty highly for the junk.

Theoretically I would say that for sailing ability the Chinese sail must fall somewhere between the Bermudan and gaff. Its flatness would tend to make it sail better to windward than the gaff and not so well off the wind. I do not doubt that the long leading edge of the Bermudan sail makes it potentially the best to windward so long as it has been properly made and stretched (a Bermudan sail that has been allowed to get out of shape is not particularly efficient). Therein lies the rub. The shape of a Bermudan sail has to be built in and its retention requires skilful tailoring and high-quality materials. The shape of the Chinese sail, by contrast, is maintained and controlled by external features in the form of the battens and sheetlets. Anybody who can cut and stitch cloth can make a Chinese sail out of almost any woven material. If one had to make do with poor quality materials and workmanship the most efficient type of fore-and-aft sail that one could make would be the Chinese; which is probably why Slocum chose it when building his "Liberdade".

High Tea on sailing trials in Hong Kong.

Handling Qualities

When sailing conditions are easy the Bermudan rig is probably a little less trouble to handle than the Chinese; though when conditions are easy the handling of the Chinese sail could hardly be described as difficult! By contrast, as conditions cease to be easy the handling of the Chinese sail remains much the same, while Western rigs become more and more burdensome.

Brian at the helm.

This is due to the degree of control given by the battens and sheetlets. A sail presents few handling problems so long as it is kept full, which is why there is a temptation with Western rigs to hold on to sail in a rising wind rather than face the blood and sweat of trying to get it in; particularly when sailing single-handed. So the helmsman continues until something breaks or until the situation becomes so obviously dangerous that he prefers to face the lesser dangers, trying to bring under control a wet and flogging mass of canvas. With the Chinese rig you carry sail until the last possible minute for a different reason: because you know that you can reduce sail anytime you like, without trouble. The sail will always come down; it cannot flog because the area of unrestrained cloth between the battens is not large enough. For the same reason it does not slat in calms. All it can do is flutter and sway - and reefing is the simplest operation in the world.

The absolute control that you have over a Chinese sail lets you cope equally easily with other situations. You can do anything with it: reef it from the top down or the bottom up, spill the wind with the sheet or the halliard, adjust its shape or its balance, sail under as much or as little of it as you like; or brail it up to see underneath. It is a little more trouble to raise the sail (principally because of the number of ropes to snag) but this is more than compensated by the ease and speed with which it is dropped. The Chinese sail comes down like a pack of cards and is gathered into its buntlines, with no more work after that than pulling it inboard and making it fast.

There is no way of heaving-to a junk, but there are other things that can be done instead. Sail can be reduced progressively until just one corner remains to hold the boat steady against the wind or it can be dropped altogether, the daggerboard and rudder hoisted clear of the water, and a sea anchor thrown over the bows. The fact that the stern is higher than the bow and the low windage of the unstayed or lightly-stayed masts should certainly assist the Chinese sailing boat to lie closer head-to-wind than ours.

A controlled gybe is better executed with a Bermudan than with a Chinese sail because it can be sheeted-in closer. On the other hand an accidental gybe in a strong wind is liable to do less harm with the Chinese sail than with ours, because the shock is more evenly distributed.

Maintenance

Any sailing ship constantly at sea requires continuous running repairs to its rigging. This is probably more true of the Chinese junk than of our boats: partly because of the large amount of rigging but more because of the poor quality of the materials that are used. The junk is generally a family boat so that there is plenty of crew available for minor repairs. More important is that the materials be cheap and easily obtainable and repairs easily executed. On these grounds the Chinese sail suits its owner very well.The materials and workmanship that go into a Chinese sail, if applied to a western rig, would blow to pieces in the first serious wind. The sail cloth is poor quality shirting-material, bound together with huge "homeward-bound" stitches. The battens are attached to the sail with a few strands of thin wire. There is no reinforcing in the way of the battens and no grommets. The wire is simply pushed through the cloth and round the batten a couple of times. The Chinese operates his boat on a very tight budget but he would use better materials if he thought they were necessary. In fact, the strains on a Chinese sail are so much less, due to the absence of flogging and slatting, that such materials are perfectly adequate. As for the workmanship, the Chinese sees no point in making it out of proportion to the materials.

My problem was slightly different. I was single-handed, I was by no means such a quick and able workman as the Chinese sailor, I was facing a long ocean passage in very rough conditions and I had more money to spend. It was worth my while to go in for better quality in the hope of reducing maintenance. Some of it was justified. I used Terylene rope for the halliards and nylon for the sheets and sheetlets. I used tough plastic hose for a chafing-strip where the battens rubbed against the mast and made the parrels of wire cable heavily greased and encased in plastic. Other measures proved to be a waste of time and money, but I had by no means reached the limits of experiment and had succeeded in cutting down the running maintenance at sea to almost nil.

I had anticipated a great deal of chafe in the Chinese sail. I found it to be much less than I had expected. Perhaps the worst chafe, and it was not important, was at the point where the after buntline passed round the foot of the sail. Otherwise chafe was only serious when the sail cloth was rubbed, wet, between two hard surfaces. I found that the sails suffered much more when reefed or furled than when extended until I had learned, when shortening sail on the starboard tack, to pull out the folds of cloth from where they might be caught and rubbed between the upper and lower battens or between the battens and the mast.

In my experience of both rigs under cruising conditions I would say that they compare differently from the point of view of maintenance, but by no means to the disadvantage of the Chinese. The Chinese sail is more liable to suffer small chafe-spots and they are much more difficult to repair at sea because the sail is so much more permanently rigged. There would be so much work in disconnecting all the battens and lines in order to get the sail comfortably stretched across one's knees out of the wind that it is easier, if the sail must be patched, to try to cope with it fully rigged.

What is lost on the roundabouts however is more than recovered on the swings. Because it does not flog the sail is less likely to tear, and if it does tear or chafe the hole will show very little inclination to spread, so that it can quite safely be left until the next calm or landfall gives leisure to deal with it. A broken batten must be repaired without too much delay; but so long as the battens remain intact the sail can be full of holes and yet retain a great deal of its efficiency. Further, although the patches may be more difficult to apply, even on dry land, they do not need to be applied nearly so well. Having learned my sail repairs on the Bermudan rig I could not bring myself to use homeward-bound stitches, but at the end I was experimenting with canvas cement - sticking on my patches - and the method gave every promise of working extremely well. Any tendency of the edge to lift might be checked with light stitching or staples.

At this point I can see the armchair yachtsmen, if they have followed me so far, rising from their seats in horror. Canvas cement! Staples! For my part I do not always equate what is seamanlike with what is old-womanish. Invisible mending is fine for those who like luxuries and can afford the time and money but in a sailing boat at sea the important thing is to keep sailing. I would not, however, advise anybody to try that technique on a western rig. The cement and staples will probably hold but they create an area of lesser flexibility, so that when the sail flogs it is likely to rip around the edges of the patch.

Finally, it is worth pointing out that there is no welded or wrought or cast or machined metal work in the Chinese rig - or none that cannot be replaced with a rope or wire - so there is no repair that cannot be executed at sea. Only simple tools need be carried, and an ample supply of bamboo and baling-wire in addition to the cordage and sail cloth and twine that are carried as normal spares.

Conclusion

It is difficult to make any sense out of the contempt with which the Chinese sailing boat is generally regarded in the West. This contempt stems from ignorance, but the ignorance itself, I think, has its roots in three main causes. The first is the almost unbelievable indifference displayed by most Europeans and Americans in the Far East to the races that live around them. Amazing the prevalence of misconceptions and the lack of any attempt or desire to find out the truth, the failure even to learn the language. If those living near China cannot be bothered even to explore Chinese cooking (the average white man in Hong Kong is acquainted with perhaps a dozen dishes out of the hundreds that exist!) why should they be bothered to learn about Chinese sailing boats?The second factor is that even in Hong Kong there are many, many varieties of Chinese sailing boat, each adapted to a different purpose. The average Westerner does not see much of the ocean-going varieties. The type mostly seen around Hong Kong harbour is the harbour lighter, a great high-walled craft with a single mast and huge tattered sails, which is built for load-carrying rather than for sailing. The sail is only an auxiliary for use with a fair wind: otherwise the vessel is towed by tug or propelled by sweeps. Anybody seeing those boats, and assuming them to be representative of the Chinese junk, would naturally conclude that the type had not very good sailing qualities!

Finally, it should be pointed out that the Chinese is not interested in the same things as we are. We, admiring their ornaments, laugh at the superstitions on which they are based. The Chinese, admiring the finish and materials that go into our boats and the care with which they are maintained, probably laugh just as much at the idea of lavishing so much sentimentality on an inanimate object. If the external appearance of a boat or vehicle or building is shoddy and neglected it creates an impression of a general unsoundness that may be quite untrue, just as a coat of paint can make something appear solid which is actually on the point of falling to pieces!

Bearing in mind the very small margins on which they work I think the Chinese are inclined to neglect maintenance beyond the point that is efficient or economic, but in this context I am concerned not with the fact but with the appearance of inefficiency, which can be deceptive. The same lack of spit and polish and the preconception that oriental dispositions are necessarily inefficient, led experienced military observers before the war to underrate the Japanese!

Comparing my experience aboard Chempaka (a Bermuda rigged cutter on which I sailed from Singapore to Manila) with that aboard High Tea I do not doubt that High Tea's was the better rig. During equally squally weather in the South China Sea the handling of Chempaka's sails became a real burden and progress was almost nil. Further, when repairs when necessary, there was almost nowhere I could find the proper quality of materials and workmanship to repair a Bermuda rig, whereas adequate quality for the Chinese rig could have been found in any large village. I do not know how Chempaka's rig would have stood up to the almost continuous winter gales of the North Pacific, and frankly I would not like to try; though I would not mind making the same journey again on a junk.

There is no such thing as an ideal sail for all conditions and I doubt whether there ever will be. Among most yachtsman the Bermuda rig has become generally accepted, and with good reason, because of its windward ability and its relative simplicity and lack of chafe. It is a good sail for easy conditions, which are the conditions under which most yachtsmen do their sailing. However, for all round cruising ability in difficult or unfamiliar conditions I think the Chinese sail is unbeatable.

Notes

Fishing junk, Cheungchow

style.

A fast and weatherly type.

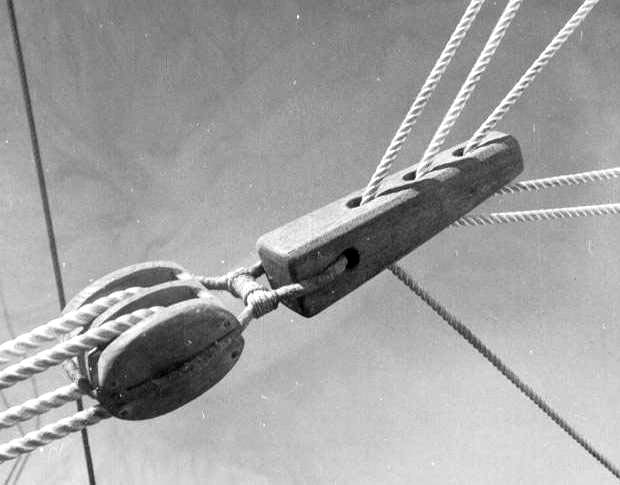

More photographs (some may be by J.R. Challacombe of San Francisco):You can't ask for a clearer photo of a euphroe and the associated sheet block:

Mainsheets. The

sheet-block was attached to the

sheetlet-euphroes by a wire grommet-strop.

Excellent view looking up the mainsail:

Mainsail viewed from

starboard side.

Note the bamboo slats on the starboard side of the sail

which

run contiguous with the battens on the port side.

Note the way the sheetlets are attached forward

of the leech so that they do not foul the

ends of the battens when going about.

Catheads. The bobstays are

not a standard fitting on

Chinese junks and it is doubtful if they served any useful

purpose.

Sampan running before

breeze in Hong Kong harbour,

an illustration of how sail is reefed. In this particular

type

the hull shows strong evidence of Western influence

though the rig is Chinese.

Mother, children and

in-laws all live and work aboard

and have no other home. On a calm day it is likely

to be festooned with washing and chickens, pigs and

vegetables also have a place aboard. All this may not

look

sailorly to our eyes, but it breeds sailors!

..

Anthony sent me a couple more photos which were not discussed in the article itself. One shows the double sheets, sister blocks, and all:

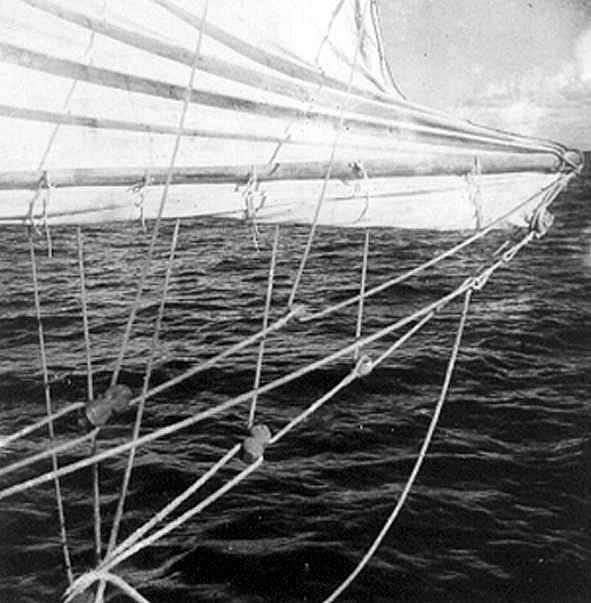

The other shows the lowest batten and the lower edge of the sail:

|

-or- Return to the Cheap Pages |

![[Port Side Rigging]](1_Port%20Side%20Rigging.gif)