THE

VOYAGE ALONE

IN THE

YAWL "ROB ROY,"

By JOHN MACGREGOR, M.A. CHAPTER IX.

Paris Regatta -- Absentees -- Novelties -- New Brunswickers -- Steam yachts -- Canoe race -- Canoe chase -- Entangled -- M. Forcat -- Challenge

WHILE the voyage in the Rob Roy's dingey on Sunday was such as we have described, it was a busy time a little further down the river at St. Cloud, being the first day of the Paris Regatta, which continued also on the Monday, and then our British Regatta occupied the next four days.

These two were under separate committees. The British Regatta was managed by experienced oarsmen, and His Royal Highness the Commodore of the Canoe Club was Patron-not a merely nominal patron, but presiding frequently at the committee meetings held at Marlborough House, and generously contributing to the funds. The Emperor of the French also gave us his name, and prizes to the amount of 1000£ were offered in a series of contests open to all the world.

The experiment of holding a regatta in a foreign country was quite novel, and there were difficulties around it which it is not convenient to detail.

Notwithstanding the hasty predictions of people who could not approve of what was originated and carried out without requiring their advice, the regatta brought together a splendid body of the best oarsmen and canoeists in the world from England, France, and America. Three Champions of England for the first time contended at the same place. The most renowned waterman came from Thames and Tyne and Humber, and eight oared boats raced for the first time on the Seine. The weather was magnificent, the course was in perfect order, and better than almost any other of equal length near any capital; the arrangements made were the very best that might be contrived under the peculiarly difficult circumstances which could not be controlled, even by a committee comprising the very best men for the purpose, and zealous it' their work; and lastly the racing itself, for spirit and for speed, and for that exciting interest which equal excellence sustained during well-contested struggles was never surpassed.

But this grand exhibition of water athletics was not seen by more than a few hundreds of persons. "Tribunes," richly draped, and with streamers flying above, and seats below for 1000 persons, often had not three people there at a time.

The French oarsmen must have been absent at some better place, and of the French public, you might see more assembled on the roadside round a dancing dog. The Emperor could not come perhaps Bismarck would not let him, and the Prince of Wales, being in his proper place as the representative of England, receiving the Sultan in London, this important duty prevented His Royal Highness from enjoying the pleasure he might well have counted upon after the trouble he had taken in connection with the British Regatta in Paris.

But after stating this disappointment bluntly, it will be remembered by all who were at St. Cloud, that there was a great ( deal of real enjoyment as well as of hard work, and the whole had a strange novelty, both in its charms and its troubles.

For crews in "hard training" to sit down to bifteck, and Medoc, omelette, and haricots verts, with strawberries and cream, and bad French jabbered round, was certainly a novelty. To see a group of London watermen, addressed in unknown tongues, but perfectly self-possessed, visiting the Exhibition in the morning and rowing a race in the afternoon, was new; and to observe the complete bewilderment of soldiers and police at the whole proceeding, which came upon them 0£ course with surprise in a country where no one reads the papers for an advertisement, except about a new play, or infallible pill -- all this was very amusing to those who could listen and look on.

The English rowing-men soon made themselves as comfortable as they could in their new quarters, and suffered patiently the disagreeables of French lodgings. They repaired their boats, often broken by the transit from London, and behaved with good humour in proportion to their good sense. Even the grumblers were satisfied, because they were provided with a new set of grievances; and so things passed off better than was expected by those who knew the real circumstances of the venture. It was the first regatta of the kind, and doubtless it will be the last.

No particular description of the various races for eight-oars, four-oars, pair-oars, and sculling, by watermen and amateurs, would be interesting to general readers; but a few notable lessons were there to be learned, which will probably not be disregarded. Those who care for the subject will find it referred to again in the Appendix. An interesting feature was added to the occasion by the arrival of four men, who came from New Brunswick, to row at this regatta. They had 1)0 coxswain to steer them, as every other boat had, but the rudder was worked (and that not much) by strings leading to one of the rowers' feet.

They contended first in a race where it was not allowed to use outrigger boats so called on account of the iron frames in them to support the oars, because the boats are so narrow that the oars cannot work on the gunwale. Moreover, they rowed in a broad and somewhat heavy or clumsy-looking craft, with common oars, like those used at sea, and they pulled a short jerky stroke, and had to go round a winding French course-indeed with apparently every disadvantage; yet they came in first, beating English and French, and winning 40£.

The same crew went in next in another race, and with another boat, an outrigger they had brought with them from the Dominion of Canada, and again they came in first, and so won another 40£.* At once "Les Canadiens" became the favourites and heroes of the day. Englishmen cheered them because they were the winners, and some Frenchman cheered them because they supposed the men were French, * whereat the hardy Canadians smiled with French politeness, but muttering the while round protestations, audible only to English ears.

*These four gentlemen, admitted to the amateur contests, declined to row against four watermen.

The river Seine was made unusually lively during the summer by the movement upon it of a whole fleet of steamers, of all shapes and sizes, and with flags often exceedingly coquet. Little screw yachts or steam launches flitted up and down, sometimes so small as to admit only three or four people on board, and a bit of awning to deflect the sun; others were crowded as usual to the limits of passengers carefully prescribed by authority. This style of locomotion is peculiarly adapted to Paris and to Parisians. It has all the heat bustle, and noise that can be desirable in nautical pleasures, and yet almost avoids those highly inconvenient undulations which open water has too often the bad taste to assume. The completion of the Thames Embankment and of the purification of our river will probably make water travelling more fashionable in London. Doubtless, the time will be when houses of Belgravian size will look from the Adelphi on the limpid Thames, and on the gay crowd hurrying along its granite margin. Then the luxurious tenant, representing some powerful trades-union or incorrupt borough will see it is time to go down to the "House," and will order his double-screw steamer round to the steps near his terrace door; and no coachman in those days need apply for a place unless he can steer. Even now, the number of miniature steamers, tug boats, and private yachts on the Thames is large and increasing; while a few years ago not one was to be seen. Most of these are pretty little things, and the best of all craft to be handled safely in the crowded waterway. The multitude of them one sees at Stockholm shows us what may be soon done in Middlesex. Several English screw yachts had come to Paris. Mr. Manners Sutton kindly lent his to the Regatta Committee, and the steam launch of the Admiralty Barge was also used, so that the umpire was able to follow each race in a proper position for seeing fair play, while the Rob Roy was anchored at the winning post to guard the palm of victory. Here, too, various bombshells were fired high into the air at the end of each race, and were supposed to correspond in number with the place of the winning boat on the programme; but they so exploded as effectually to confuse the audience and spectators they were meant to enlighten as to "who had won:" which uncertainty, we all know, is one of the principal excitements of a regatta, and it can be sometimes prolonged even until the day afterwards. The other features of these rowing matches on the Seine may be left to the reader's imagination if he has seen a regatta before; and if he has not seen one, he could not well apprehend them by reading. The canoe races, however, being more novel, have another claim on attention.

One of these was for fast boats, and to be decided only by speed. The other was a "canoe chase," in which dexterity and pluck were required for success.

For the canoe race three Englishmen had brought from the Thames three long boats with long paddles, and they were the three fastest canoes in England, so far as could be proved by previous trials. Against these, three French canoes were entered, all of them short, and with short paddles. One of these, propelled by an Englishman (resident in Paris), came In easily first, and the second prize was won by a Frenchman. Here, surely, was a good sound lesson to English canoemen who wish to paddle fast on still water, in a boat useless for any other purpose, and slower at last than a skiff with two sculls. Accordingly, we must accept the beating with thanks. Some further remarks on the matter are given in the Appendix, for those who desire to profit by the defeat.

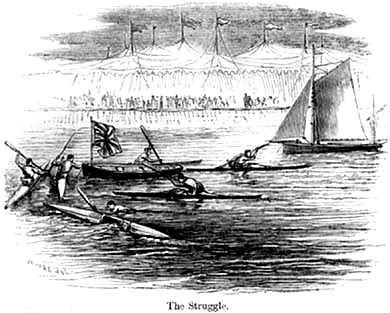

The canoe chase, first instituted at the Club races on the Thames, was found to be an agreeable variety in nautical sport, and productive of at good deal of amusement. Therefore, two prizes were offered at the Paris Regatta for a canoe chase, open to all the " peoples." Five French canoes entered, but there was only one English canoeist ready in his Rob Roy to meet all comers.

The canoes were drawn up on land alongside each other, and with their sterns touching the lower step of the " Tribune " or grand stand. It was curious to observe the various positions taken up by the different men, as each adopted what he thought was the best manner of starting. One was at his boats stern; another, at the side, half carried his canoe, ready to be "off; " another grasped the bow; while the most knowing paddler held the end of his "painter" (or little rope) extended from the bow as far as it would reach.

All dashed off together on being started, and ran with their boats to the water. The Frenchmen soon got entangled together by trying to get into their boats dry; but the Englishman had made up his mind for a wetting, and it might as well come now at once as in a few minutes after, so he rushed straight into the river up to his waist, and there fore, being free from the crowding of others, he got into his boat all dripping wet, but foremost of all, and then paddled swiftly away. The rest soon followed; and all of them were making to the flag boat anchored a little way off, round which the canoes must first make a turn. Here the Englishman, misled by the various voices on shore telling him the (wrong) side he was to take, lost all the advantage of his start; so that all the six boats arrived at the flag-boat together, each struggling to get round it but locked with some other opponent in a general scramble.

Canoe-chase. The Struggle. [132]

Next, their course was back to the shore, where they jumped out and ran along, each one dragging his boat round another flag on dry land, amid the cheers and laughter of the dense group of spectators, who had evidently not anticipated a contest so new in its kind, and so completely visible from beginning to end. Again, dashing into the water, the little struggling fleet paddled away to another flag-boat, but not now in such close array. Some stuck in the willows or rushes, or were overturned and had to swim; and the chance of who might win was still open to the man of strength and spirit, with reasonably good luck. Once more the competing canoes came swiftly hack to shore, and were dragged round the flag, and another time paddled round the flag-boat; and now he was to be winner who could first reach the shore and bring his canoe to the Tribune: a well-earned victory, won by the Englishman, far ahead of the rest.

The whole affair lasted not much longer than might be required to write its history; but the strain was severe upon pluck and muscle, and called forth several qualities very useful in life at sea, but which mere rowing in a straight race does not require, and cannot therefore exhibit. Instantly after this exciting contest, a Frenchman challenged the winner to another chase over the same course. But as the challenger had not thought fit to enter the lists and test his powers in the chase, which was open to him like the rest, it would, of course, have been quite unfair to allow him, quite fresh, to have a special race with the hard-worked winner, though the Englishman was quite ready to accept the gage.

Among the visitors to the regatta was M. Forcat, whose peculiar system of propelling boats I have mentioned in the account of a former voyage; and he brought up for exhibition, and for the practical trial by the winner of the canoe chase, a very narrow and crank boat, rowed by oars jointed to a short mast in front of the sitter, and thus obtaining one of the advantages possessed by canoeists, that their faces are turned to the bow, and so they see where they are going.

It is no doubt an enormous disadvantage that in ordinary rowing your back is turned upon the course, with all its dangers and beauties; and this inconvenience is only put lip with because you can go faster when rowing sitting with your back foremost, amid scenery of no account on a river which only serves to float the skiff but not to please the eye. As for travelling on strange waters in this style, with face to the rear, it is just as if you were to walk backwards along the road, and think you could still appreciate the picturesque by looking over your shoulder at rare intervals, or by a stare to the rear upon landscapes ever retreating from you. But though M. Forcat's boat had the rower's face to the bow, the form and size of the nondescript novelty were not to be understood in a moment, and we tried to dissuade our young canoeist from entering hastily a new sort of boat very easily capsized. He had his own wit, and his own way, however, because he was a Scot, and only "English" in the sense we use that word for "British" -- and too frequently used it is, to the dire offence of the blue lion of the North, whose armorial tail is well known to be so punctiliously correct as to the precise curl and make up of its "back hair."

"He's upset," they cried in a minute or so. But we might well let so good a swimmer take his chance; so he merely pushed the boat ashore, and then took a pleasant and gratuitous swim, until he was finally captured and put into the Rob Roy's cabin, and changed his wet clothes as rapidly as a modest man dare to do behind a plaid screen and before the curious world.

Therefore in boats, as well as business and politics, we may learn lessons from one another, both on the water as well as on shore : from Canada, as to the steering and the stroke; from France, as to the fast canoe; and from England, as to the man.

It was to see this regatta and to help in it that the Rob Roy had pushed her way to Paris. Six hundred miles of river navigation in a seagoing boat would else have been by no means advisable and often did I feel how much out of place was the steady lifeboat yawl upon a calm inland water like the Seine.

Before the arrival of my little yacht, a challenge had been sent to her to sail on the Seine against a French yacht there. To this I replied that it would be scarcely a fair match for the Rob Roy, a sea craft, racing on a river known only to one of the competitors; but that the yawl would gladly sail a match with any French yacht having only one man on board -- the course to be at sea either one hundred miles for speed, or one week for distance, and without communication with any other boat on the shore. No answer came.

CHAPTER X.

Dawn music -- Cleared for action -- Statistics -- Blue Peter -- Passing bridges -- A gale -- A shave -- Provisions -- Toilette -- An upset -- Last bridge -- A peep below -- Cooking inside -- Preserved provisions -- Soups

THE Rob Roy was very pleasant lodgings when moved down to the lovely bend at St. Cloud. Sometimes she was made fast to a tree, and the birds sung in my rigging, and gossamers spun webs on the masts, and leaves fell on the deck. At others I struck the anchor into soft green grass, and left the boat for the day, until at night returning from where the merry rowers dined so well in training, and after a pleasant and cool walk "home" by the river side, there was the little yawl all safe on a glassy pool, and her deck shining spangled with dewdrops under the moon, and the cabin snug within -- airy but no draughts, cool without chill, and brightly lighted up in a moment, yet all so undisturbed, without dust or din, and without any bill to pay.

Awake with the sun at five, there was always the same sound alongside. First, the sweet murmurings of the water cleft by my sharp bow at anchor, and gliding along the smooth sides only a few inches from my ear, and sounding with articulate distinctness through the tight mahogany skin, and next there was the muttering chatter of the amateur fisherman, who was sure to be at his post, however early.

This respectable personage, not young but still hearty, is in his own boat -- a boat perfectly respectable, too, and well found in all particulars, flat, brown, broad, utterly useless for anything but this its duty every morning.

Quietly his anchor is dropped, and lie then fixes a pole into the bottom of the river, and lashes the boat to that, and to that it will be fixed until nine o'clock; at present it is five. He puts on a grey coat, and brown hat, and blue spectacles, all the colours of man and boat being philosophically arranged, and as part of a complicated and secret plot upon the liberties of that unseen, mysterious, and much considered goujon which is poetically imagined to be below. It has baffled all designs for this last week, for it is a wily monster, but this morning it is most certainly to be snared.

Rod, line, float, hook, bait, are all prepared for the conflict, and the fisherman now seats himself steadily in a sort of armchair, and with stealth and gravity drops the deceitful line into hidden deeps. At that float he will stare till lie cannot see. He looks contented; at any rate, no muscle moves in his face, though envy may be corroding his soul. After an hour he may just yield so much as to mutter some few sounds, or a suppressed moaning over his hard lot (and that is what I hear in my cabin). Then at last he rises with a determined briskness in his mien, and the resentment against fate from an ill-used man, and he casts exactly three handfuls of corn or bread-crumbs into the water, these to beguile the reluctant obstinate gudgeon, who, perhaps, poor thing, is not so much to blame for inattention after all, being at the time just one hundred and fifty yards away, beside those bulrushes.

Indeed that very idea seems to have struck the fisherman too, and he marks the likely spot, and will go there to-morrow, not today -- no, he will always stick one day at one place. How he moves to or from it I do not know, for the man and boat had always come before I saw them, and I never stopped long enough to see them depart. Four men fished four mornings thus, and only two fish were caught by them in my presence.

The regatta is over, and Nadar's balloon is in the sky, but seeming no bigger than other balloons, so soon does the mind fail to appreciate positive size when the object it looks at is seen alone. It is the old story of the moon, which "looks as large as a soup-plate," and yet Nadar's Géant is the largest balloon ever seen, and it carries a house below it instead of a car -- a veritable house, with two storeys, and doors and windows. The freedom of its motion sailing away reminds me that the Rob Roy ought to be moving too -- that she was not built to dabble about on rivers, but to charge the crested wave; and, indeed, there was always a sensation of being pent up when she was merely floating near the inland cornfields, and so far from the salt green sea; and this, too, even though pleasant parties of ladies were on board, and boys got jaunts and cruises from me which I am certain pleased them much: still the reef-points on her sails rattled impatiently for real breezes and the curl of the surf, while the storm mizzen was growing musty, so long stowed away unused.

Next day, therefore, the Blue Peter was flying at the fore, and the Rob Roy's cellar had its sea stock laid in from "Spiers and Pond," of ale, and brandy, and wine. Before a fine fresh wind, with rain pelting cheerfully on my back, we scudded down the Seine. To sail thus along a rapid stream with many barges to meet, and trees overhanging, and shoals at various depths below, is a very capital exercise, especially if you feel your honour at stake about getting aground, however harmless that would be. But the Seine has greater difficulties here, because the numerous bridges each will present an obstacle which must be dealt with at once, and yet each particular bridge will have its special features and difficulties, not perhaps recognized when first you meet them so suddenly. I recollect that old Westminster Bridge was a very dangerous one for a boat to sail through, because the joints between the voussoirs, or lines of stones under the arch, were not horizontal as in most other bridges, but in an oblique direction, and several times when my mast has touched one of these it was borne downwards with all the power of a screw. The bridges on the Seine were not often high enough to allow the yawl to pass under, except in the centre, or within a few feet on one side or other of the keystone, and as the wind also, just at the critical moment when you reach such places, is deflected by the bridge, and the current of water below rushes about in eddies from the piers, there is quite enough of excitement to keep a captain pretty well awake in beating to windward through these bridges; and the wind must be dead ahead a great part of the time, because the river bends about and about with more and sharper turns than almost any other of the kind.

Though sun and wind had varnished my face to the proper regulation hue, in perfect keeping with a mahogany boat, yet the fortnight of fresh water had softened that hardiness of system acquired in real sea. My hands had gradually discarded, one after another, the islands of sticking-plaster, and a whole geography of bumps and bruises, which once had looked as if no gloves ever could get on again -- or rather as if the hands must always be encased in gloves to be anywhere admissible in a white-skinned country.

But now once again outward bound, though still so many miles from the iodine scent of the open sea, and the gracious odour of real ship's tar, one's nerves are strung tight in a moment. The change was hailed with joy, though sudden enough, from the glassy pond-like water at St. Cloud, lulled only by gentle catspaws, half asleep and dreaming, to the rattling of spars and blocks, and hissing of the water, in the merry whistling gale in which we were now rapt away.

At Argenteuil there are numerous French pleasure-boats, and the Rob Roy rounded to in a good berth. Next day there was a downright gale, so I actually had to reef before starting, because in a narrow river the work of beating against the wind is very severe on legs and arms, and especially on one's hands, unless they are hardened, and kept hard by constant handling of the strong ropes.

At length we put into a quiet bay, where another river joined the Seine, and moored snugly under the lee of a green meadow, while trees were waving and rustling above in the breeze. It was fir from houses, for I wished to have a quiet night on the river Oise, as the tossing of the former night had almost banished sleep.

But soon enough the inquisitive natives found the yawl in her hiding-place, and sat on the grass gazing by the hour. The surroundings were so much like a canoe voyage that I felt more strongly than ever the confinement to a river, while the sea would have been so open and grand under such a breeze. Therefore I gave up all idea of sailing down the Seine any more, and decided to get towed to Havre, and launch out fairly on the proper element once more.

Yet it was fine fun to row about in the dingey, and to discover a quaint old inn, and to haul up the tiny cockleshell and dine. Here they were certainly an uncouth set, and did not even put a cloth on the table, nor any substitute for it -- a state of things seen very seldom indeed in the very outermost corners of may various trips.

Faithful promise was made by a man that he would rouse me from slumber in my cabin under the haybank at the passing of the next steamer, be it light or dark at the time. The shriek of the whistle came in the first hours of morning, and the man ran to tell it, with one side of his face shaven and the other frothed over with lather.

Being towed down is so like being towed up the river, that we need merely allude to general features in the voyage westward.

At one pretty town we stopped to unload cargo for some hours, and I climbed the hills, scaled the old castle walls, and dived into curious tumbledown streets. The keeper of the newspaper-shop confessed to me his own peculiar grievance, namely, that he often sent money to England in reply to quack advertisements, but never had any reply. He seemed to be too "poli" to credit my assertion that there are "many rogues in perfidious Albion," and on the whole he was scarcely shaken in the determination to persevere in filling their pockets, though he might empty his own.

An old man at a lock was delighted by a New Testament given to him. "I know what this is; it is Protestant prayers. Oh, they are good." Then he brought his wife and his grandchildren, and every one of them shook hands.

It was not very easy to get one's sea-stores replenished in the continuous run down the Seine. Sometimes I saw a milkman trundling his wheelbarrow over a bridge, and, jumping on shore, I 'waylaid him for the precious luxury, or sent off a boy for bread, and butter, and eggs; but, of course, the times of eating had nothing to do with any hours, or recurring sea sons for a meal: you must cook when you can, and snatch a morsel here or there, in a lock or a long reach of the stream. At night the full moon sailed on high, and the crew lay down with their faces over the steamer's side, chatting with their English comrade till it was far past bedtime, for we shall be off at three to-morrow morning.

The steam in the boiler first warns of the coming bustle as its great bubbles burst inside, and rattle the iron plates. Then they, more frequent and tighter bound, give out a low moaning, hidden sound; and if my boat touches the side of the steamer, there is a strong vibration through all her sonorous planks, until some tap is turned m the engine, and the rush of steam leaps into the cylinder as if indignant at its long restraint. You had better get up (there is no dressing, for the simple reason that there has been no undressing), and in two minutes you are fresh and hearty, though it is only a few hours since you dropped to rest.

Rouen looks as if it would be all that is pleasant for a sailing-boat to rest in. Never was a greater deception. It is difficult to find an anchorage, and impossible to get a quiet berth by the quay. The bustle all day, and the noise all night, keep you ever on the tenterhooks; though, as these discomforts are caused by the active commerce of the port, one ought to bear them patiently.

In one of the numerous mélées of barges, boats, and steamers whirling round and round, amid entangled hawsers, and a swift stream, we had at last to invoke aid from shore, and a number of willing loungers gladly hauled on my rope. Some of these men, when I thanked them, said they had more to thank me for -- the books I had given them in my voyage up. Still, with all this aid, the Rob Roy was inextricably entangled with other heavier craft, and, in shoving her off, I tumbled overboard, and had to put up with a thorough wetting; so, after a warm bath ashore, more à la mode, I returned to my little cabin for a profound sleep.

Rain, almost ceaseless for a whole day and night it, had searched the smallest chink, and trickled ungraciously into my very bedroom. But I suspended an iron teacup in the dark just over my body, so that this little stream was intercepted. This was the first really hard pressure of wet on the Rob Roy, and all the defects it brought to light were entirely remedied afterwards at Cowes.

On each of the four preceding nights I had been aroused for the next day's work at three, or two, or even one o'clock, in the dark, and yet for one night more there was to be no regular repose.

My mast had been made fast to the quay wall, but in forgetfulness that on a tidal river this fastening must be such as to allow for several feet of fall as the water ebbs. Therefore, about the inevitable hour of one o'clock, in the dark, there was a loud and ominous crack and jerk from the rope, and I knew too well the cause. In the rainy night it was a troublesome business to arrange matters, and next day was a drowsy one with me, spent in the strange old streets of the town.

The policeman had orders to call me at any hour when a steamer went by, and, being hooked at last to the powerful twin-screw Du Tremblay, with a pleasant captain, I rejoiced to near the very last bridge on the river, with the feeling, "After this we are done with freshwater sailing."

It was a suspension-bridge, and the worthy captain forgot all about the Rob Roy and her mast, when he steered for a low part, where his own funnel could pass because it was lowered, but where I saw in a moment my mast must strike.

There was no time to call out, nor would it have availed even to chop the towing-line with my axe, for the boat had too much "way" on her to stop. Therefore I could only duck down into the well, to avoid the falling spar and the splinters.

The bridge struck the mast about two feet from the top, and, instead of its breaking off with a short snap, the mast bent back and back at least four feet, just as if it were a fishing-rod, to my great amazement. The strong vibration of its truck (pomme the French call it), throbbed every nerve of boat and man, as it scraped over each plank above, and then the mast sprang up free from the bridge with such a switch and force, that it burst the lashings of both the iron shrouds merely by this rebound.

Now was felt the congratulation that we had carefully secured a first rate mast for the Rob Roy, one of the pieces of Vancouver wood, proved by the competitions lately held, to be the strongest of all timber.

The moments of expected disaster and of happy relief were vivid as they passed, but I made the steamer stop, and on climbing the mast I found not even the slightest crack or injury there. Henceforth we shall trust the goodly spar in any gale, with the confidence &c only to be had by a crucial test like this.

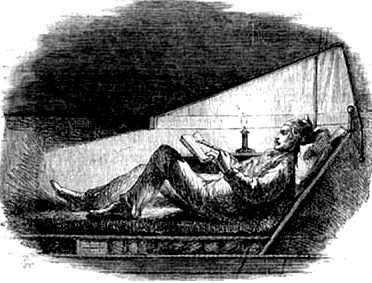

As we shall soon be at sea again, but the river is calm enough here, perhaps this will be a fit opportunity for the reader to peep into Rob Roy's cave, as it was usually made up for the night.

The floor of the cabin is made of thin mahogany boards, resting on crossbeams (p. 150). The boards are loose, so that even in bed I can pull one up, and so get at my cellar or at the iron pigs of ballast. The bed is of cork, about seven feet long and three feet wide. On this (for it was rather hardish) I put a plaid,* and then a railway rug, which being coloured, bad been substituted for a blanket, as the white wool of the latter insisted on coming off, and gave an untidy look to my thick blue boating-jacket. One fold of the rug was enough for an ample covering, and I never once was cold in the cabin. A large pillow was encased by day in blue (the uniform colour of all my decorations), and it was stripped at night to be soft and smooth for the cheek of the sleeper.

The Cabin. [150]

Putting under this my coats and a regulation woven Jersey, with the yacht's name worked in red across its breast in regular sailor's fashion, the pillow became a most comfortable cushion, and the woodcut shows me reclining in the best position for reading or writing, as if on a good sofa.

* I found that a common Scotch plaid resisted wet longer than any other material, if it was in an inclined position, and it could be readily dried by banging it from the mast in the wind.

On my right hand behind is a candle-lamp, with a very heavy stand. It rests upon a shelf, which can be put in any convenient place by a simple arrangement.

In the sketch already given at p.39, there is a tarpaulin spread over the well, and this was used on one occasion when we had to cook in rain while at anchor. There was another method of cooking under shelter, and we employed it on the only other occasion when this had to he done, namely, to shut up the cabin and to cook inside it, using the portable "canoe cuisine," which is described in the Appendix. But as this is meant to be employed only on shore, it does not answer well on hoard, except in a calm; and, moreover, the boat generated by the lamp was too much in a little cabin. Even a single candle heats a small apartment and it is well known that a man can get a very good vapour-bath by sitting over a rush-light, with blankets fastened all round.

On the same side, and below the boxes, "Tools" and "Eating," already mentioned, are two large iron cases, labelled "Prog," -- a brief announcement which vastly troubled the brains of several French visitors, whose English etymology did not extend to such curt terms.

In these heavy boxes are cases of preserved meats, soups, and vegetables, and these I found perfectly satisfactory in every respect, when procured at a proper place (Morel's in Piccadilly). Here you can get little tin cases, holding half a pint each and sealed lip hermetically. The best, according to my taste, were those of "Irish stew," "Stewed steak," "Mulligatawny," "Ox-tail," and "Vegetable soup," all in the order named. "Preserved peas" were not quite so good, but the other viands were all far better than can be had at any ordinary hotel, and were entirely without that metallic or other "preserved" flavour so soon discovered in such eatables, and even by a palate not fastidious.

To cook one of these tins full -- which, with bread and wine is an ample dinner -- you cut the top circle with the lever-knife, but allowing it to be still attached by a small part to the tin, and fold this lid part back for a handle.

Then put the tin into a can of such a shape and size that it has about half an inch of water all round the tin, but not reaching too high up, else it may bubble over when boiling, and as you can use saltwater or muddy water for this water-jacket, it will not do to sprinkle any of that inside the tin.

The can is then hung over the Russian lamp, and in six minutes the contents of the tin are quite hot. Soup takes less time, and steak perhaps a little more, depending on the facility of circulation of the materials in the tin and the amount of wind moderating the heat. The preserved meat or soup has been thoroughly cooked before it is sold, and it has sauce, gravy, and vegetables, and the oxtail has joints, all properly mixed. Therefore, in this speedy manner your dinner is prepared, and indeed it will be smoking hot and ready before you can get the table laid, and the "things" set out from the pantry.

Concentrated soup I took also, but it has a tame flavour, so it was put by for a famine time, which never came. As for "Liebig's Extract of Meat," you need not starve while there is any left, but that is the most we can say in its favour.

© 2000 Craig O'Donnell

May not be reproduced without my permission.