THE

VOYAGE ALONE

IN THE

YAWL "ROB ROY,"

By JOHN MACGREGOR, M.A. CHAPTER XVII.

Continental sailors -- Mal de Mer -- Steam launches -- Punt chase -- The ladies -- Fireworks -- Catastrophe -- Impudence -- Drifting yachts -- Tool chests -- Spectre ship -- Where am I? -- Canoe v. yawl -- Selfish -- Risk and toil -- Ridicule

THE Regatta days opened with wind and rain; but even at the best of times, the sight of a sailing match from on shore is like that of a stag-hunt from on foot -- very pretty at the start and then very little more to see. It is different if you sail about among the competing yachts. Then you feel the same tide and wind, and see the same marks and buoys, and dread the same shoals and rocks as they do, and at every turn of every vessel you have something to learn. No one can satisfactorily distribute the verdict " victor " or " vanquished " in a sailing match between the designer, the builder, the rigger, and the course, the weather, the rules, the sailor of each craft, and chance; though each will conduce in part to the success or failure in every match. Still there is this advantage, that the loser can always blame, and the winner can always praise, which of these elements lie finds most convenient. But if a sailing-match has little in it quite intelligible, even when you see it, the account of a past regatta is well worth keeping out of print -- so be it then with this one, the best held at Cowes for many years.

The large crowds that attended, and their obstinate standing in heavy rain, were in marked contrast to the phlegmatic and meagre interest of the few French who came to the regatta at St. Cloud. But it is such occasions that remind us of England being a land of seamen, while continental sailors are at best of the land, except in northern nations.

Once it was my lot to sail in a small screw steamer along the coast of Calabria. Of the four passengers one was a Neapolitan officer, who embarked in full uniform ; and with light tight boots and spurs, and clanging sword, he stalked the quarter-deck, that is, he took three steps, and was at the end, and three steps back.

In going out of Messina I saw we should have a tough bit of sea outside, and was soon prepared accordingly He did not so, and the first bursting wave wet him through in a moment, and down lie went below. Some hours afterwards I descended too, and a melancholy sight was there, with very lugubrious sounds.

In the cabin was a huge tub full of water, and the officer (spurs, boots, and all) was sitting in it with his legs out of one end and his head groaning and bellowing from the other. This was his specific for seasickness, and for three days he behaved about as well as a fractious baby who sadly wants a good whipping. It is no discredit to a man to be seasick. Nelson, it is said, was so far human. But it is somewhat unmanly for an officer to whine and blubber like a child, and yet I have several times seen this phenomenon abroad. When we came into Naples this hero was again in full feather; boots, spurs, and sword, stalking the quarter-deck as if no tub and tears had intervened.

The rapid introduction of steam launches into use for our large English yachts adds quite a new feature to every grand regatta. Here again, however; the French navy led the way, and England follows somewhat tardily. The French fleet at the Cherbourg review, some years ago, had a swarm of these fussy little creatures buzzing about the great anchored ironclads. English steam launches were built to carry each a gun, and so they are bluff and slow. Our Admiralty declined to allow a race between these and the French launches in Paris, else, no doubt, the superior speed of the French boats would have astonished John Bull. Lately, however, there is the idea started that a steam launch need not itself carry a gun, and so may be built for speed and general convenience, while, if it is at any time wanted in war service, it may well tow another boat with a gun in it. This seems a sensible improvement. Better still, the English Government have had a steam launch built for them by Mr. S. White, of Cowes, who builds so many for yachts and other peaceful purposes; and the great success it achieved in its first official trial may result in an extension of the use of steam launches for innumerable purposes.

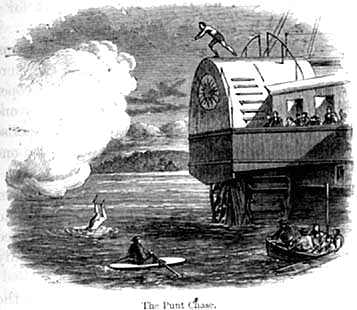

Some excellent rowing-matches, after the Regatta in Cowes, were varied by a "punt chase," an amusement thoroughly English, but not well enough known by a distinguished debater in the House of Commons to allow it to be tried in Paris among our British oarsmen. The Cowes people were far wiser, and they had two of these capital exhibitions of aquatic athletics.

One man in a punt is chased by four in a rowboat who have to catch both him and his boat within ten minutes.

Of course his path is devious and tortuous on the water, his resort being quick turns, while the chasers gain in speed. After numerous close escapes, he leaps into the water. Then if the pursuers hold his boat it clogs them in following him, and if they follow him while his boat is left free he manages to escape round some tangled mass of shipping, and so regains his boat for a new start.

This is the sort of thing that tries both swimming and pluck in the water; as well as mere muscle or wind in a boat. It is to racing proper what a hunt is to a fiat race. Rowing is only one small part of boating, and it is apt to monopolise our favour chiefly because many can row for one that can boat.

In one of these punt chases at Cowes the punter had several times plunged into the sea, and amid shouts and cheers he was always closely followed by one of his chasers who swam almost equally well.

At length the brave punter swam over to the 'Alberta,' one of the Queen's steam-yachts, which had several of the Royal Princesses and others on board, who kindly thus patronized the races, and their presence was thoroughly appreciated by us all. The hardy sailor scaled the yacht, and actually ran among the ladies -- who doubtless were much amused, and indeed they tittered vastly. Then he mounted the lofty paddle-box, closely followed by his resolute pursuer, who would not be shaken off. With one moment of hesitation the punter took a splendid "header" into the sea, and as he was thus descending from the paddle-box the gun fired, showing that the Punt Chase ten minutes had expired. The pursuer could then, of course, have given up the chase as done. He had lost, and could not win now. But there was still in him that fine free boldness which superadds brave deed to stern duty, and amid a burst of cheers he too leaped down into the sea.

The Punt-Chase [229]

The first diver, however, had heard the wished for gun as he fell, and so he claimed his prize when he came up all red and watery, and both had well gained the applause of the spectators.

It Is not for one who has rowed fifty races with pleasure to underrate, far less to disparage, mere rowing; but still we maintain that for the encouragement of pure manliness, and the varied capacities useful in a sailor's life, one punt chase is far better than ten of the others.

The "voyage alone" had culminated at Cowes when the splendid exhibition of fireworks closed the grand show of British yachting. It was a beautiful sight those whizzing rockets speeding from wave to sky, and scattering burning gems above to fall softly from the black heaven; those glares of red or green that painted all the wide crescent of beauteous hulls, and dim, tall masts with a glow of ardent colour; and the 'bouquets' of fantastic form and hue, with noise that rattled aloft while thousands of paled faces cheered loud below. To this day the deck of the Rob Roy bears marks of the shower falling quietly, gently down, but still with a red scar burned in black at the last.

The luggage is all on board again, and our "Blue Peter" flies at the fore, for the Rob Roy will weigh anchor now for her homeward voyage. The Ryde Regatta was well worth seeing, and she stopped there in an uneasy night, but we need not copy the log of another set of sailing matches.

Thus in a fine evening, when the sun sunk ruddy and the breeze blew soft, we turned again to Brading harbour, and, just perhaps because we had come safely once before, there was listless incaution now, as if Bembridge reef could not be cruel and hard on a fine evening such as this.

Various and doubtless most true directions had been given to me as to entering this narrow channel :-

"Keep the tree in a line with the monument; that's your mark."

But when you come there and see the monument, there are twenty trees; and which then is the tree to guide by? Here, therefore, and in mundane things on land too it is alike, the misapprehension of a rule was worse than the chance mistake of undirected motherwit. A horrid crash brought us suddenly to rest; the Rob Roy had struck on a rock. Though I was lax at the time, and lolling and lazy, yet presence of mind remained. Down came the sails, out leaped the anchor, and shoving, and hauling, and rowing did their best; but no, she was firmly berthed on one of the north-west rocks. Presently a malicious wave lifted her stern round, and the rudder was aground on another sharp ledge, until by sounding and patience I at last got her free and rowed out through a channel unconscionably narrow, and then ran the sails up, and the yawl was safe again, sailing smoothly, with a deep sigh of deliverance.

A sailing-boat had put off from the shore to help, seeing the catastrophe, but I signalled to her, "Thanks -- all right now," and she went back. Soon another boat that had rowed out came near, and the man in her determined to be a salvor, whether or no, and leaped on board the yawl. I made him get off to his boat; I had not invited him, nor had he asked permission to board me. He could see it was the other man's job, and he ought to have obeyed the signal, as did the other. Grumbling heavily, he at length asked me to tow him in. "Well," I said, "why, yes, I will give you a tow, though you have been very impudent." But the moment he came near he jumped on board again, resolved to save me, though I might protest ever so hard. Once more, then, I bundled him into his boat, and this time rather by deeds than words. He kept up a volley of abuse all the way to the shore, and there I gave my yawl in charge to the first man, who had acted right both in coming out and in going back when signalled. A hospitable Captain R.N. offered me his moorings (as good as a bed for a boat), and asked me to breakfast next day, which was accepted, "subject to wind;" especially as he was of the clan "Mac" like his guest.

Calm night falls on the Rob Roy, in a little inland lake, profoundly still, more quiet, indeed, in respect of current, tide, or wind, or human being, than any night of the voyage. It was very difficult to turn in below with such a moon above and water quite unruffled. So there was a long lean-to on propped elbows, and reverie reeled off by the yard. Daybreak gray, with a westerly breeze, at once dissolved the breakfast engagement and carried the Rob Roy to sea, with her kettle briskly boiling ; and now we are fairly started on our voyage to the Thames again. But the glowing sun also took its morning meal, and greedily ate up the wind; and so the yachts from Ryde could be seen far oft; looking farther off in a misty curtain, all only drifting with the tide, while they raced their hardest for a cup. Yet there is science and skill in drifting well. If the skipper has no wind to show his prowess in with sails, he must win by his knowledge 0£ current, tide, and channel, while he seems perhaps to be carried along helplessly. One after another the graceful racers slowly rounded the Warner lightship, anti then each sunk back, as it were, into the gauzy distance until they seemed like white pearls dotted on gray satin, and the Rob Roy was alone again, while the fog thickened more. Land was shut out then sky, then every single thing, and the glazed sea seemed to stiffen as if it had set flat and smooth for ever.

To know that this state of things was to last for hours would make it intolerable, but the expectancy of every moment buoys up the mind in hope, and every past moment is buried as you reach thus forward to the next coming.

Then the inexorable tide turned dead against me, and down went my anchor; for; at any rate, we must not be floated backwards. Tool chest opened, and hammer and saw are instantly at work, for there are still "things to be done" on board, and when all improvements shall have been completed then vacant hours like these will be tedious enough; but never fear; there is no finality in a sailing-boat, if the brain keeps inventing and the fingers respond.

Out of the thick creamy fog a huge object slowly loomed, with a grand air of majesty, and a low but strenuous sound as it came nearer and clearer to eye and ear. It was an enormous Atlantic steamer; and it went circling round and round in ample bends, but never too far to be unexpected again. Sometimes her great paddles moved with a measured plash, but slow, until she dissolved before my eyes into a faded vision. Again, when hidden, there would still come a deep moaning from her hoarse fog whistle out of the impenetrable whiteness, and she again towered up suddenly behind, ever wheeling, gliding on vapour and water so commingled that you could not say she floated, but was somehow faintly present like the dim picture on a canvas screen from a magic lantern half in focus. She was searching in the fog for the 'Nab' lightship, thence to take new bearings and cleave the mist in a straight course at half-speed for Southampton. When she found the 'Nab' she vanished finally, and I was glad and sorry she was gone.

After long waiting, the faintest zephyr now at last dallied with my light flag for a minute, and the anchor was instantly raised. A schooner; also outward bound, soon slowly burst its way through the cloudy barrier; and I tried to follow her; but she too melted into dimness, and left me in a noiseless, sightless vacancy, except when the distant gong of the lightship told that they also had a fog there. How did the ancients by any possibility manage to sail in a fog without a compass? In those days, too, they had no charts ; yes, and there was no "Wreck chart," to tell at the year's end all the havoc strewn at the bottom of the sea.

Well we sailed on, and on, always seeming to sail on into pure cotton-wool, which blushed a little with an evening tint as the sun tired down, and so here was a long day told off and ending; but where exactly am I now as darkness falls?

You will say "Why, the chart tells that, of course;" and so it does, if you have anything like sure reckoning to indicate what part of the mazy groups of figures on it to look for as your probable place; otherwise a dozen different places in it will all suit your soundings, and eleven of them are wrong.

Consider the data for our calculation. The Rob Roy had been carried by two tides; one this way, the other that. She had sailed on three different tacks, that is, in various angular directions, and with different speeds, and these complicating forces had acted for times very uncertain. Where is she now? an all-important question for settling the start-point in a night cruise, and on a dangerous coast.

The last time I was sailing in fog was on the Baltic, in my canoe, where, just at the nick of time, a lookout man was descried on a high ladder far overlooking the low rocky islands of the Swedish coast, and he speedily showed me that my bow was then pointed exactly wrong for the desired haven.

This may be the time, perhaps, to compare the canoe voyage with the yawl cruise, even if we cannot settle the question so often put to me, a Which was the most agreeable?"

A canoe voyage can be enjoyed by several men, each in a separate boat, and yet all in a combined party; that is, with distinct responsibility but united companionship. The yawl cruise devolves both toil and care on one alone, but he also has all the pleasure, and so it might be pronounced at once to be more selfish than the other voyage. But after a score of tours, in large and small parties, I see that selfishness is quite independent of the number concerned. A man who is pleasing his wife or his children in a tour I do not count at all; for everything that delights or benefits then is of course a pleasure to him. Or again, he may journey with ten companions, and his travelling circle will indeed be larger, but the centre of it may be after all the same.

Of the thousand tourists who rush out over the Continent each summer there is little check on selfishness by meeting people in trains, steamers, and hotels for a temporary acquaintance, which is speedily dissolved as soon as the interests or the likings of the companions are not coincident.

Unselfishness appears to consist in doing good when it is not exactly pleasant to do it, and to people who are not in our own groove, or in "our set" but like the people invited in the feast prescribed by Christ, and for whom we work as a duty, whether it is immediately agreeable or not. It is giving up our own will to God's command, and yet obeying this ungrudgingly; and yet our own pleasure may be most in giving others pleasure, and we can be lavish of labour for others while selfish at the core. Thus it seems to be very difficult ever to be unselfish in the sense that it is often absurdly insisted upon; namely, that others are everything and yourself nothing. Nevertheless, after all casuistry, we know what is meant by "selfish," as an undue regard. But the whole of an action is to be looked at, and it does not become selfish because we do one part of it alone. A man who steps out from a crowd to pluck flowers alone on the edge of the cliff may bring back a bouquet that will give fragrant pleasure to them all, while another who stays in the group of gatherers may gather none at all or may be very selfish about his handful. Our lonely labour may, in fact, be most of all useful for other people in the end.

The anxieties of the canoe trip are more varied and less heavy than in a sailing cruise.

In the yawl I was always sure of food and lodging, but then in the canoe one does not fear wind, wave, calm, and fog; for, at any rate, one can at the worst take the canoe ashore. The risk of a total loss of the canoe is only fifteen pounds gone, but the other shipwreck risks ten times as much, and whereas each canoe danger can usually be avoided, those met in sailing at sea are often to be encountered without any escape.

The physical endurance required in a canoe is more under control of a previous arrangement. The muscular exertion with the paddle is generally voluntary, while that in the yawl was often hardest when one wanted most to rest. You need scarcely be forced to go on two days and two nights without sleep, as will be seen was the fate in the yawl.

The scenery in traversing land and water in a canoe is of course more varied than in sailing always at sea, but the perils of the deep have a grandeur and wideness that seem to rouse far more the inner soul, and with more profound emotions. The thoughts during a night storm at sea are of a higher strain than those in passing the rapid in a river.

Finally, there is at first a sense of incongruity in the appearance of a boat on shore, in a cart, on a train, and under a roof; and you have to meet an inexplicable but evident smile at the whole affair; which perhaps comes from pity, certainly from ignorance, and it may be from contempt; whereas a sailing-boat crossing the deep is doing what people in ports and ships know very well about, and if your boat keeps on doing it successfully they cannot despise the deed because the boat that does it is small. A man who comes to the "meet" on a little pony will not be laughed at if he is always well in at the death. so

Perhaps the voyage alone in a yawl will not be soon repeated by other people as that in a canoe, for this manner of touring has become popular at once. A number of voyages were made in Britain in 1866, and of the 120 members of the Canoe Club, the large majority have been floating fast and far in the past summer also.

One of these, a distinguished University oar; sailed * at night across the Channel from Dover to Boulogne, paddled through France and sailed to Marseilles, and thence from Nice to Genoa, through the Italian lakes, the Swiss lakes, and by the Reuss to the Rhine home again. A second coasted along England, and paddled across the Channel from the French side.

*He had wisely fitted a centre board in his 14-feet canoe, and this sliding keel answered well for sailing .

Another went down the Danube from its source to Donauwert, and then down the Moldau and the Elbe. Three more went half round the rocky coast of Skye -- a hundred miles -- and launched their 'Rob Roys' on Loch Corruisk, the first boats ever known there; and two of them crossed to the island of Rum, over sixteen miles of sea.* The Clyde and the Thames, and other rivers had their canoeists; and one paddled through the beautiful Irish streams, while another carried his boat off to India. A branch of the Canoe Club is being formed in China, and several others in the United States.**

*A writer complacently denied, a few months before these voyages, that a canoe could cross a bay eight miles wide.** For more about the Canoe Club, see the Appendix. It has excited the good humour of 'Punch' and 'Fun,' and a Comic Annual treats it to forty sketches, while in one other paper the critic was evidently in the "dumps ;" but it came out that his first essay at the paddle had resulted in an upset!

CHAPTER XVIII.

Bedtime -- A trance -- Thunderings -- Charts -- Light dims -- Night flies -- First running -- Newhaven -- On the gridiron -- Mr. Smith -- Tumbledown walls -- Derelict

"WHERE is the yawl now?" was the question we had asked in the fog, and the natural answer is that the chart would tell, of course. The vapour has for a little cleared up, so let us look at the small slice of chart copied on page 246. It is crammed, you see, with figures and names of banks, buoys, and beacons; but the only thing to be seen in the horizon around us, is the Owers light behind, and about N.W. in its bearing. The tide will soon turn against our progress towards the east, therefore we tack towards shore, so as to be within anchorage soundings should it become needful to stop, for the wind has just changed rather suspiciously, and we can even hear the sound of the drums at Portsmouth as they beat the taptoo. One or two bright meteors shoot in the heavens, reminding us that this is one of their usual epochs -- the 14th of August.

Now we are in ten fathoms by the lead, and we must anchor here, for the tide has fully turned and the wind has lulled, and perhaps it will do to sleep for six hours here before going on again.

The beautiful phosphorescence of the sea on this occasion was an attractive sight and I could follow the line of my hemp cable by the gleam of silver light which enfolded it with a gradually softened radiance from the surface of the sea, down, down to an unseen depth, where, in sooth, it was dark enough.

The tide stream pressed the cable back into a curve, and thus making it sparkle. To anchor for the night riding by tide or stream, is not pleasant; for then the wind may cross your hatch, and blow and rain in sideways, whereas if you ride at anchor to the wind alone, the draught comes always from the front and so it can be better provided for, and the boat does not roll much even if she pitches.

The gentle motion of riding with a chain-cable is quite in contrast to that when anchored by a rope; for this latter will jerk and pull, while the heavier chain, laid in a drooping curve, acts as a constant spring that eases and cushions every rude blow.

I intended to start again with any freshening breeze, and to get into Littlehampton for the night; therefore the small anchor and the hemp cable were used so as to be more ready for instant departure, and well it was thus.

Time sped slowly between looking at my watch to know the tide change, and dozing as I lay in the cabin -- the dingey being of course astern; until in the middle of the night) lapsing through many dreams, I had glided into that delicious state when you dream that you are dreaming. On a sudden, and without any seeming cause, I felt perfectly awake, yet in a sort of a trance, and lying still a time, seeking what could possibly have awakened me thus. Then there came through the dark a peal of thunder, long, and loud, and glorious.

How changed the scene to look upon! No light to be seen from the Owers now, but a flash from above and then darkness, and soon a grand rolling of the same majestic, deer-toned roar.

Now I must prepare for wind. On with the life-belt, close the hatches, loose the mainsail, and double reef it and reef the jib. Off with the mizzen and set the storm-sail, and now haul up the anchor while yet there is time; and there was scarcely time before a rattling breeze got up, and waves rose too, and rain came down as we sailed off south to the open sea for room. Sea room is the sailor's want: the land is what lie fears more than the water.

We were soon fast spinning along, and the breeze brushed the haze all away, but the night was very dark, and the rain made it hard to see. Now and then the thunder swallowed all other sounds, as the cries of the desert are silenced by the lion's roar.

Sometimes there was an arch shining above as the flashes leaped across the upper clouds, and then a sharp upright prong of forked lightning darted straight down between, while rain was driven along by the wind, and salt foam dashed lip from the waves. It seemed like an earthly version of that heavenly vision which was beheld in Patmos by the beloved John :-" And I heard as it were the voice of a great multitude, and as the voice of many waters, and as the voice of mighty Thunderings." *

* Revelation, xix, 7.

How well our English word "thunder" suits the meaning in its sound, far better than tonnerre or tonitru.

In the dark a cutter dashed by me, crossing the yawl's bows, just as the lightning played on us both. It had no ship-light up, shameful to say.

I shouted out "Going south ?" and they answered "Yes; come along off that shore."

From the bit of chart here copied (covers only a few miles) it will be understood what kind of shore we had to avoid. There was quite water enough for our shallow craft but it was the twisting of currents and tides that made the danger here.

The breeze now turned west, then South, and every other way, and it was exceedingly perplexing to know in time what to do in each case, especially as the waves became short and snappish under this pressure from different sides, and yet my compass quietly pointed right, with a soft radiance shining from it, and my mast-light in a brighter glow gleamed from behind me* on the white crests of the waves.

One heavy squall roughened the dark water, and taxed all my powers to work the little yawl; but whenever a lull came or a chance of getting on my proper course again, I bent round to "East by North," determined to make way in that direction.

In the middle of the night my compass lamp began to glimmer faint; and it was soon evident that the flame must go out. Here was a discomfort: the wind veered so much that its direction would be utterly fallacious as a guide to steer by, and this difficulty would continue until the lightning ceased. Therefore, at all hazards, we must light up the compass again. So I took down the ship-light from the mizzen shroud, and held it between my knees that it might shine on the needle, and it was curious how much warmth came from this lantern. Then I managed to get a candle, and cut a piece off, and rigged it up with paper inside the binnacle. This answered for about ten minutes, but finding it was again flickering, I opened the tin door, and found all the candle had melted into bright liquid oil; so this makeshift was a failure.

* It was hung on the port mizzen shroud. To hang it in front of you is simply to cut off two of your three chances of possibly seeing ahead.

However, another candle was cut, and the door being left open to keep it cool, with this lame light I worked on bravely, but very determined for the rest of my sailing days to have the oil bottle always accessible. Finally the wind blew out the candle, though it was very much sheltered, and the ship-light almost at the same time also went out suddenly. Then I lay to, backed the jib, opened the cabin hatch, got out the oil, thoroughly cleaned the lamp, put in a new wick, and lighted it afresh, and a new candle in the ship's light; then we started all right once more, with that self-gratulation at doing all this successfully, under such circumstances of wind, sea, and rain, which perhaps was not more than due.

What with these things, and reefing several times, and cooking at intervals, there was so much to do and so much to think about during the night, that the hours passed quickly, and at last some stray streaks of dawn (escaped before their time, perhaps) lighted up a cloud or two above, and then a few wave-tops below, and soon gave a general gray tint to all around, until by imperceptible but sure advance of clearness, the vague horizon seemed to split into land and water, and happily then it was seen plainly that the Rob Roy had not lost way in the dark. As soon as there was light enough to read we began to study Shoreham in the Pilot book, and neared it the while in the water; but though now opposite the Brighton coast, it was yet too far away to make out any town, for we had stood well out to sea in the thunderstorm. All tiredness passed off with the fresh morning air, and the breeze was now so strong that progress was steady and swift.

It may be remarked how a coast often looks quite different when you are fifteen or twenty miles out at sea, from what it does when you stand on the beach, or look from a row boat close to the land. So now we were puzzled to find out Brighton, one's own familiar Brighton, with its dull half-sided street, neither town nor bathing town, its beach unwalkable, and all its sights and glories done in a day. We might well be ashamed not to recognize at once the contour of the hills, so often trudged over in square or in skirmish in the Volunteer Reviews.

The chain-pier was, of course, hardly discernible at a great distance. But the "Grand Hotel" at last asserted itself as a black cubical speck in the binocular field, and then we made straight for that; Shoreham being gradually voted a bore to be passed by, and Newhaven adopted as the new goal for the day.

We had shaken out all reefs, and now tore along at fall speed, with the spray-drift sparkling in the sun, and a frolicsome jubilant sea. The delights of going fast when the water is deep and the wind is strong -- ah ! these never can be rightly described, nor the exulting bound with which your vessel springs through a buoyant wave, and the thrill of nerve that tells in the sailor's heart, "Well, after all, sailing is a pleasure supreme.

Numerous fishing-vessels now came out, with their black tanned sails and strong bluff bows and hardy-looking crews, who all hailed me cheerily when they were near enough, and often came near to see. Fast the yawl sped along the white chalk cliffs, and my chart in its glazed frame did excellent service now, for the wind and sea rose more again; and at length, when we came near the last headland for Newhaven, we lowered the mainsail and steadily ran under mizzen and jib. Newhaven came in sight, deeply embayed under the magnificent cliff which at other times I could have gazed on for an hour, admiring the grand dashing of the waves, and we had to hoist mainsail again, so as to get in before the tide would set out strongly, and increase the sea at the harbour's mouth every minute.

It was more than exciting to enter here with such waves running. Rain, too, came on, just as the Rob Roy dashed into the first three rollers, and they were big and green, and washed her well from stem right on to stern, but none entered further. The bright yellow hue of the waves on one side of the pier made me half afraid that it was shallow there, and hesitating to pass I signalled to some men near the pier-head as to which way to go, but they were only visitors. The tide ran strongly out, dead in my teeth, yet the wind took me powerfully through it all, and then instantly, even before we had rounded into quiet water, the inquisitive uncommunicative spectators roared out, "Where are you from?" "What's your name?" and all such stupid things to say to a man whose whole mind in a time like this has to be on sail and sea and tiller. I think that in a port like Newhaven the lookout man in charge ought to come to the pier-head when he sees a yacht entering in rough weather, and certainly there is more attention to such matters in France than with us.

During this passage from the Isle of Wight I had noticed now and then when the waves tossed more than usual, that a dull, heavy, thumping sound was heard aboard the yawl, and gradually I concluded that her iron keel had been broken by the rock at Bembridge, and that it was swinging free below my boat. This idea added to the anxiety of getting in safely, lest such an appendage might touch the ground; and to make sure of the matter we took the Rob Roy at once to the gridiron, and laid her alongside a screw-steamer which had been out during the night, and had ran on a rock in the dark thunderstorm. The "baulks " or beams of the gridiron under water, were very far apart, and we had much difficulty in placing the yawl so as to settle down on two of them, but the crew of the steamer led me well, and all the more readily, as I had given them books at Dieppe, a gift they did not now forget.

Just as the ebbing tide had lowered the yawl fairly on the baulks, another steamer came in from France, crowded with passengers, and the waves of her swell lifted my poor little boat off her position, and rudely fixed her upon only one baulk, from which it was not possible to move her; therefore, when the tide descended she was hung up askew in a ludicrous position of extreme discomfort to her weary bones; but when I went outside to examine below, there was nothing whatever amiss, and gladness for this outweighed all other troubles, and left me quite ready for a good sleep at night.

For this purpose we rowed the yawl into a quiet little river, and lashed her alongside a neat schooner, whose captain and wife and children and their little dog 'Lady' were soon great friends, for they were courteous people, as might be expected in a respectable vessel; it is generally so.

Now the Rob Roy settled into soft mud for a good rest of three days, and I went to the Inn where Mr. Smith landed from France in 1848, after he had given up being Louis Philippe.

The Inn trades upon this fact, and it has other peculiarities -- very bad chops, worse tea, no public room, and a very deaf waitress; the whole sufficiently uncomfortable to justify my complaint, and it must be a very bad inn indeed that is not comfortable enough for me.

Here I was soon accosted by a reader of canoe books, and next day we inspected the oyster-beds, and a curious corn-mill driven by tidewater, confined in a basin -- one of the few mills worked by the power of the moon. Also we wandered over the new sea fortifications, which are built and hewed by our Government one week, and the week afterwards if there comes a shower of rain they tumble down again. This is the case, at any rate, with the Newhaven fortress, and we must only hope that an invading army will not attack the place during the wrong week.

Three steamers in a day, all crowded with Exhibition passengers, that was a large traffic for a small port like Newhaven; but it did not raise the price of anything except ham sandwiches, and I bought my supplies of eggs and butter and bread, and walked off with them all, as usual, to the extreme astonishment of an aristocratic shopwoman.

In crossing a viaduct my straw hat blew off into a deep hole among mud, and I asked a boy to fetch it. The little fellow was a true Briton. He put down his bundle, laboriously built a bridge of stones, and at imminent risk of a regular mudbath, at length clasped the hat. His pluck was 50 admirable, that he had a shilling as a reward, which, be it observed, was half the price of the hat itself two months before, a No.2 hat, while my No.2 straw had the Canoe Club ribbon.

This incident put an end to quiet repose, for the boy-life of the town was soon stirred to its lowest depth, and all youngsters with any spirit of gain trooped down to the yawl, waiting off and on for the next day also in hopes of another mishap as a chance of luck to them.

The dingey too had its usual mead of applause; but one rough mariner was so vociferous in deriding its minuteness, that at last I promised him a sovereign if he could catch me, and he might take any boat in the port. At first he was all for the match, and began to strip and prepare, but his ardour cooled, and his abuse also subsided.

Many Colchester boats were here, nearly all of them well found, and with civil crews, who were exceedingly grateful for books to read on the Sunday, and resting among them was a little yacht of five tons, which had been sent out with only one man to take her from Dover to Ryde. Poor fellow! he had lost his way at night and was unable to keep awake, until at last two fishermen fell in with the derelict and brought him in here, hungry and amazed; but I regarded him with a good deal of interest as rather in my line of life, and I quite understood his drowsy feelings when staring at the compass in the black, whistling rain.

© 2000 Craig O'Donnell

May not be reproduced without my permission.