THE

VOYAGE ALONE

IN THE

YAWL "ROB ROY,"

By JOHN MACGREGOR, M.A.

THE PARIS REGATTA.

THOUGH the French cannot row so well as the English, they seem to he more venturesome in experiments than we are. Once they taught us the best forms for seagoing sailing vessels. Perhaps we have a lesson yet to learn from the same quarter in the build of our boats; and at any rate if we come to see that a French boat with an English crew in it would beat an English boat manned by a French crew, we shall ask whether there is not a limit to our present mode of adding minute and vexatious items to the manner of rowing, beyond "good time" and "strong pull," until at length half a man's energy is wasted in the process, and only half is left for the propulsion-like the lessons of writing-masters which bother you most about holding the pen.

The success of the four New Brunswick men in Paris against good English crews, as well as French, may be useful in calling our attention to the needless encumbrance of a coxswain for four oars, to the liability to reform and improvement possessed by an oarsman's stroke (like all things else), and to the flat floor of boat as opposed to the narrow round one now in vogue, though there is no department of mechanical construction we can point to that is so persistently conservative (in its worse sense) as that of boatbuilding.

This arises partly from the fact that boats for the Universities are often designed by men who cannot row, or by good oarsmen who cannot build; but it seems to be principally owing to the fact that a new boat cannot really be tried for speed except in a race, and if this race be between " duffers" the experiment is not decisive, while if it is between first-rate men there is (naturally and rightly) great reluctance to risk the race by adopting for the first time any "new-fangled system."

For speed, the English had used the same form in a canoe, which succeeds in a skiff-great length, and they could thus also use a long paddle, which it was thought would be of great advantage.

This was to forget that the stroke of the canoe-paddle is only on one side at a time, and if it be applied far from the side of the boat it tends to turn the boat round.

Thus the long paddle, while affording a long stroke, was also expending part of the power in causing the canoe to swerve alternately right and left ; and though the effect of this was much counteracted by the great length of the boat, it was a counteraction gained only by neutralizing some of the muscular effort.

The Frenchman built his fast canoe on an opposite principle. It was short, narrow, and light to an extraordinary degree, and razée down to the water's edge. His paddle was short, and its blades of a heart shape with the broader part inwards,and thus working with the centre of effort as near as possible to the gunwale of the boat. The stroke with this had to be short and quick, and though it would distress the "wind" of a man at least as soon as his muscles, in a short race this is the very thing we expect if all the powers are to be taxed to the utmost. There were good reasons therefore for the French canoes being faster than the English.

Each person may have his own taste as to the particular kind of boat or gee, or horse, he may like, and the special purpose he wants it for. One prefers a fast clipper yacht, a repeating rifle, or a racer horse ; while another likes better a good sea-boat, a strong single-barrel, or a safe hunter.

In the matter of canoes we happened to design one that would do to travel in water, and to carry on laud, one that would sail and hold luggage, would bear hard thumps and heavy seas; and if these qualities are all combined, we cannot wonder that positive speed must be sacrificed.

Rowboats now and then have journeyed on foreign rivers, but a crew would scarcely take an "outrigger eight " to go down the Danube in, nor would a French fast canoe be comfortable for a cruise in the Swedish lakes.

Therefore it was not because rowboats were to be superseded that the Rob Roy canoe was devised, but to open a new field of land and water hitherto untraveled, if not utterly inaccessible to any rowboat.

A little pardonable jealousy was, however, to be anticipated at first from captains and coxswains of rowing crews who saw their best oar absent from the usual monotonous parade up and down the same identical mile of water, working like a lever in a machine in silence, and at the year's end learning only to "pull," and when he found that the truant member (whose absence has spoiled his boat for the day) had gone away by an early train and launched his Rob Roy on some winding stream, had paddled, sailed, and waded, and shoved, dragged, and carried his craft, though all alone, and now proclaimed the proceeding as at any rate a variety.

Ah, but that word "alone "-it is seized on at once as if it were a necessary feature of canoeing, whereas the fact is that five canoeists, if they choose to paddle in company, can easily do so very much nearer to each other than five men rowing in separate boats, and can moreover still maintain that perfect freedom to go separate, which is totally surrendered when we enter a four-oar.

Such matters, however, are not to be settled by argument on the side of the canoe, nor by jeers from the rowboat. They must be submitted to trial, and then it will be found that while rowing is as noble a pastime as before, there is a new water companion afloat with new charms and capabilities, and quite able to weather a laugh as well as a wave.

The speedy appreciation of the paddle was shown by the fact that hi its first year the Canoe Club enrolled 100 members, each with a canoe, and some with two or three, and if the few who aimed at speed have not been at first successful, the many who desire to develop other qualities have had most happy days with the paddle.

In 1807 the Club had 130 members, and a twelve mile race on the Thames on December 7 had six entries of canoeists eager to paddle even in a frosty air.

THE BIBLE AT THE EXHIBITION.

WHAT will result from this Bible-giving and tract-giving first, to the receivers? has any tumult or scandal or jest offense been caused by it, as was so much dreaded? None has been mentioned. Will any good be promoted, as is so much hoped? Much, if there be any reality in what we know of seed thus sown elsewhere. Nay, it does seem impossible that the message of God to man, and the words of the Lord Jesus Christ to sinners, and the pleadings of the Holy Spirit with a fallen world, should he entirely fruitless on so many thousands; and if but a few seeds fall on good ground there, then all the work is well repaid.

But, besides the actual first recipients of these books, let us recollect the many and far-off families and towns to which they are carried, even if only as souvenirs of the Exhibition. If the Welsh drovers who carry books to Wales which they have received at a London cattle-fair, come back next year with money to buy more, as they have often done, surely the little Testament from the Bible Society, given in Paris, will be shown and read in many distant parts of Europe; and the Emperor number will be opened out in French garrisons to see what news for soldiers is in the 'British Workman' brought by a comrade from the Champ do Mars.

Rebuke and ridicule often fall upon those who dare to give a paper to a stranger, however good are its contents, and however much good they may do the reader. This is, to a certain extent, a salutary check upon indiscriminate, ostentatious, or wasteful distribution, though, of course, nothing can wholly prevent these, any more than yen can tie men's tongues from silly words or their hands from foolish actions in public.

But it is almost as amusing to see the nervous timidity of some people in this matter, as it is distressing to see the thoughtless action of others.

Men who are scandalized to see a gentleman speaking to a group of workingmen near some thoroughfare-whatever be the subject of their talk, will not hesitate to make a speech themselves on the open hustings to the most noisy crowd, and to brave a shower of eggs in return ; but then they have a point to gain, a great purpose in hand, and they are in earnest . The remarks already made as to the distribution of books at the Exhibition apply specially to the building first described, and where my attention was at first arrested. The separate building, however, occupied by the British and Foreign Bible Society was another fountain from which the Truth flowed freely, and the following are extracts from a very interesting account of what was done there published by the Society in October : "Our issues last week were 5554 copies, while, up to the present time, they amount to about 65,000 copies, of which about 12,000 copies have been sold. In addition, nearly a thousand copies of the New Testament in French and English, and French and German, have been placed in the Hotels and Pensions of Paris, and already- many have spoken with joy of finding the Word of God when entering their bedrooms ill this gay and pleasure-loving city. The military and police still; come flocking to our depot in the Park in large numbers ; and the eagerness with which they receive the sacred Volume, often commencing to read it once they depart, shrews that our large and liberal grants to them are duly appreciated. Strange to say, the number of priests coming to us, so far from diminishing, has of late considerably increased; and I must record, to the credit of many of them, that they have expressed warm sympathy with our object.

"A few days ago an English Roman Catholic priest came and asked for an English Bible, which he received, his friend, a French priest, receiving another in his language; and thus it is that those who profess to belong to the only true Church come to those whom they have been taught to regard as heretics, to obtain that which their own Church does not supply, and without which there can be no true Church at all. Roman Catholic priests, doubtless, may have the Vulgate, the only authorized version of their Church; but for vernacular translations they must look elsewhere, for their Church does not encourage them, and we never hear of Roman Catholic missionaries in any part of the world translating the Word of God.

"Up to this time, 500 Roman Catholic priests have received the Word of God from us, and, on the whole, those who have come to us have been far from showing an unfriendly feeling. As far as the metropolis is concerned, this is doubtless, in a great measure, owing to tire liberal and enlightened sentiments of the Archbishop of Paris, who, in his last charge, urges men to study God's three great books-Nature, Conscience, and Revelation ; and who, I believe, is far from looking with disfavor on the work of Bible distribution in France."

THE ROB ROY CUISINE.

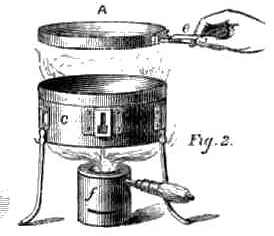

This has been designed after numerous experiments with the various portable cooking-machines which I could procure for trial, and, as it succeeds better that any of them, and has been approved by trial in my own voyage, and in another to Iceland, besides numerous shorter trips, it may be of some interest to describe the apparatus here.

The object proposed was to provide a light but strong apparatus which could speedily boil water and heat or fry other materials in wet and windy weather, as well as in fine days, and with fuel enough carried in itself for several days' use.

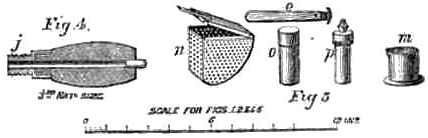

Fig 1 is a section of the cuisine as it is made up for carrying. There is a strong waterproof bag about one foot high, and closed at the top by a running cord. At the bottom is the cuisine itself, a, which occupies a space of only six inches by three inches, and has the various parts packed inside except the drinking-cup b.

Provisions, such as bread and cold meat or eggs, may be stowed in the bag above the cuisine, and if the string be attached to a nail fixed in the boat, the whole will be kept steady.

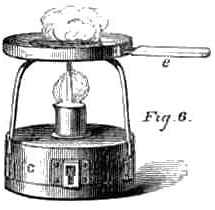

For use, when it is desired to boil water, the cuisine being opened the lower part is a copper pan, C, fig. 2, with a handle, e, which can be fixed either into a socket in the side of the pan, or another in the side of the lid, as represented in figs. 2 and 6.

Three iron legs also fix into sockets and support the pan over the spirit-lamp, f, by which the pan, two-thirds full of liquid, will be boiled in five minutes.

The lamp is the main feature of the apparatus, and it is represented in section in fig. 3. It consists of two cylinders, one within the other. The space between these (shaded dark) is closed at top and bottom, and a tube 6, fixed through the bottom rises with an open end inside, and another (a small nozzle) curved upwards in the open internal cylinder. Another tube, A, opens into the annular chamber between the cylinders, and it has a funnel-shaped mouth at the outer end, through which the chamber may be filled, while a screw in the inside allows a handle, fig. 4 (in section), to have its end, j, screwed in. Through this handle is a small tube open at both ends until the outer one is closed by a little cork, which will be expelled if the pressure within is so high as to require escape by this safety-valve.

The outer cylinder of the lamp, being larger than the inner one, has a bottom, k fig. 3, which forms a circular tray of about two inches wide and half an inch deep.

The original form of the lamp which was first brought to notice by the cook of the Canoe Club (Mr. F. F. Tuckett, of Bristol), had a detached tray for the bottom, and this has some advantages, but for the admission of air into the lamp two saw-cuts are made, each about an inch long, one of them is shown below f, fig. 2, and thus the lamp and tray are united in one compact piece while still there is access for air.

To put the lamp in operation, unscrew its handle from the position in fig. 2, so that it will be as in fig. 3 and 4. Then from a tin flask (which has been packed with the rest of the things in the inn) pour spirits of wine--or, if the odor is not objected to, methylated spirit, into the measure m, fig. 5, and from that into the interior of the lamp through the opening at h. Next screw on the handle, and place the lamp level under the pan, and pour nearly another measure full into the tray. Set fire to this, and shelter it for a few seconds if there be much wind.

In a short time the flame heats the spirits in the closed chamber, and the spirituous steam is forced by pressure down the tube, and inflames at the nozzle, from which it issues with much force and some noise in a lighted column, which is about one foot in height when unimpeded.

This powerful flame operates on the whole of the bottom and lower edge of the pan, and it cannot be blown out by wind nor by a blast from the mouth, but may be instantly extinguished by placing the fiat bottom of the measure upon it.

The cover may be put on so as to rest with the flat bottom downwards, and with or without the handle. If tea is to be made with the water when it boils, the requisite quantity is to be placed in the tea vessel n, fig. 5, which has perforated sides, and, its lid being closed, this is placed in the water, where it will rest on the curved side, and can be agitated now and then for a minute, after which insert the handle in the socket of the pan and remove the lamp, allowing the tea to infuse for four minutes, when the tea-vessel may be removed and the made tea may be poured out into the cup. The dry tea can be conveniently carried in a paper inside the tea-vessel. Salt is carried in a box o, and the matches are in the box p. A clasp-knife and fork and a spoon are also supplied. Coffee may be best carried in the state of essence in a bottle.

If bacon is to be fried, or eggs to be poached or cooked sur le plat, they may be put into the lid and held by hand over the lamp-flame, so as to warm all parts equally, or the slower heat of a simple flame may be employed by lighting the measure full of spirits and then placing it on the bottom of the upturned pan as shown at fig. 6, where it will be observed that the three legs are placed in their sockets with the convex curve of each turned outward, so that the lid, as a frying-pan, can rest upon their three points.

The spirit-flask contains enough for six separate charges of the lamp, and the cost of using methylated spirits at 4£ 6d. a gallon is not one penny a meal. The lamp-flame lasts for fifteen minutes, and the weight of the cuisine, exclusive of the bag and cup, is about two pounds.

These cuisines, improved by the suggestions obtained in their use, are made by Mr. Hepburn, of 61, Chancery Lane, London, of the best materials and workmanship, and at the price of two and a half guineas.

The lamp above described was used daily in my yawl, but the other fittings were on a more enlarged scale, as extreme lightness was not then required.

THE CANOE CLUB.

Formed 1860.

Commodore.- H.R.H. THE PRINCE OF WALES.

Captain.- J. MACGREGOR, Esq., 1, Mitre Buildings, Temple.

Mate.- Js. INWARDS, Esq., Canoe Cottage, Queen's-Rd., Erith.

Purser.- Lieut-Col. WRIGHT, Stapleford Hall, Nottingham.

Cook.- F. F. TUCKETT, Esq., Frenchay, Bristol.

OBJECTS.- To improve canoes, promote canoeing, and unite canoeists.

- MEANS.-

- (1.) Arranging and recording canoe voyages.

(2.) Holding Meetings annually for business and bivouac, for paddling and sailing, and for racing and chasing in canoes over land and water.

- MEMBERS.-

- Any gentleman who owns or has owned a canoe, or who hires one by the year, may be elected by a unanimous vote of the Committee, or 'nay be proposed by the Committee at a Meeting of members, and elected by ballot (one black ball in five to exclude). Entrance, 1£; Annual Subscription, 10s.; payable on the anniversaries of each member's election. No prize can be taken unless the winner has paid his subscription. Each candidate should state whether he can swim.

- Honorary MEMBERS.-

- Ladies and gentlemen approved by the Committee. Annual Subscription, 1£. ; member's wives or sisters Annual Subscription, 10s.

- Each member agrees to withdraw from the Club, if requested so to do by three-fourths of the members present at a Meeting, where the subject has been discussed after special notice.

COMMITTEE.-

- The Committee shall consist of the officers and six members, to be elected annually at the Autumn Meeting. The Committee may fill up vacancies in its number, and the members of it are eligible for re-election.

MEETINGS.-

- There shall be a Spring Meeting and an Autumn Meeting yearly, at times and places to be fixed by the Committee. Members may be elected at either of the Meetings. A Special Meeting may be called by the Committee, and shall be called by them if a requisition is made by twelve members for a special purpose.

- At the Spring Meeting the Mate shall present a statement of proposed voyages and races. At the Annual Meeting the Mate shall present the Annual Report, the Log of Voyages, &c., and a Finance Statement.

CANOES.-

- Each canoe shall be entered in the Club-book in a name approved by the Committee.

- Each member on election is required to send to the Mate the name and a minute description of the canoe, and a portrait of himself, for insertion in the Club-book. The Committee have power to declare the election of a member void, if, within one month of his election, or three months from each anniversary of it, lie fails to comply with the rules as to his canoe and subscription.

Logs.- Each member is requested to forward from time to time to the Mate a record of his voyages, travels, or races with any other particulars likely to be of use to the Club.

Club Cipher.- The burgee, ribbon, and ciphered-paper of the Club, to be used only by members, shall he according to the patterns determined at the Autumn Meeting, and kept by the Committee. The Club uniform is not to be worn on Sundays.

Races.- The races and Club matches are to be under the management of the Committee.

© 2000 Craig O'Donnell

May not be reproduced without my permission.