THE

VOYAGE ALONE

IN THE

YAWL "ROB ROY,"

By JOHN MACGREGOR, M.A.

CHAPTER I.

Project -- On the Stocks -- Profile -- Afloat alone -- Smart lads -- Swinging -- Anchors -- Happy boys -- Sea Reach -- Good looks -- Peep below -- Important trifles -- In the well -- Chart -- Watch on deck -- Eating an egg -- Storm sail

IT was a strange and pleasant life for me all this summer, sailing entirely alone by sea and river fifteen hundred miles, and with its toils, perils, and adventures heartily enjoyed.

The two preceding summers I had paddled alone in an oak canoe, first through central Europe, and next over Norway and Sweden; but though both of these voyages were delightful, they had still the drawback, that progress was mainly dependent on muscular effort, that food must be had from shore, and that I could not sleep on the water.

In devising plans to make the pleasure of a voyage complete then, many cogitations were had last winter, which resulted in a beautiful little sailing-boat; and once afloat in this, the water was my road, my home, my very world, for a long and splendid summer,

The perfect success of these three voyages, has been due mainly to the careful preparation for them in the minute details which are -- as I think -- too often neglected. To take pains about these is a pleasure to a man with a boating mind; but it is also a positive necessity if he would ensure success, nor can we wonder at the fate of some who get swamped, smashed, stove-in, or turned over, when we see them go adrift in a craft which has been huddled into being by some builder ignorant of what is wanted for the sailor traveller, and is launched on unknown waters without due preparation for what may come.

I resolved to have a thoroughly good sailing boat -- the largest that could be well managed in rough weather by one strong man, and with every bolt, cleat, sheave, and rope well considered in relation to the questions: How will this work in a squall ?-on a rock ?-in the dark ?-or in a rushing tide ?-a crowded lock; not to say in a storm?

The internal arrangements of my boat having been fully settled with the advantage of the canoe experiences, the yacht itself was designed by Mr. John White, of Cowes -- and who could do it better? She was to be first safe, next comfortable and then fast. If indeed, you have two men aboard, one to pick up the other when he falls over, then you may put the last of the above three qualities first but not prudently when there is only one man to do the whole.

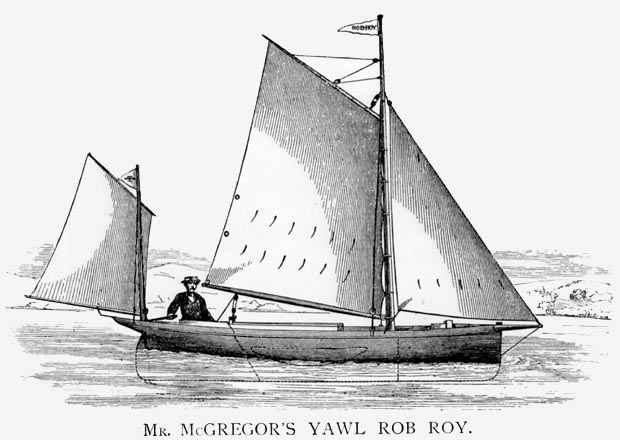

The Rob Roy was built by Messrs. Forrest, of Limehouse, the builders for the Royal National lifeboat Institution, and so she is a lifeboat to begin with. Knowing how much I might have to depend on oars now and then, my inclination was to limit her length to only 18 ft., but Mr. White said that 21 ft. would "take care of herself in a squall."

Therefore that size was agreed upon, and the decision was never regretted, while at the same time I should by no means advise any further increase of dimensions. One great advantage of this larger size, was that it enabled me to carry in the cabin of my yawl,* another boat, a little dingey or punt to go ashore by, to take exercise in, and to use for refuge in last resource if shipwrecked, for this dingey also I determined should be a lifeboat and yet only eight feet long. The childhood of this boat was somewhat unhappy, -- and as she grew into shape she was quizzed unmercifully, and people shook their heads very wisely, as they did at the first Rob Roy canoe.

* The description of the yawl in its various parts and fittings will be given as occasion requires in this narrative, and other minutiae interesting chiefly to practical sailors will be noticed in the Appendix.

Now that we can reckon about two hundred of such canoes, and now that this little dingey has proved a complete success and an unspeakable convenience, the laugh may be forgotten. However, ridicule of new things often does good if it begets caution in changes, and stimulates improvement. Good things get even benefit from ridicule, which may shake off the plaster and paint, though it will not shiver the stone.

Thoroughly to enjoy a cruise with only two such companions as have been described, it is no doubt of importance that the man who is to be with them should also be adapted for his place. He must have good health and good spirits, and a passion for the sea. He must learn to rise, eat, drink, and sleep as the water or winds decree, and not his watch. He must have wits to regard at once the tide, breeze, waves, craft, buoys, and lights; also the sails, pilot-book, and compass, and more than all, to scan the passing vessels, and to cook, and eat, and drink in the midst of all. With such pressing and varied occupations, he has no time to feel "lonely," and indeed, he passes fewer hours in the week alone, than many a busy man in chambers. Of all those I have met with who have travelled on land or sea alone, not one has told me it was "lonely," though some who have never tried the plan as a change upon life in a crowd, may fear its unknown pleasures. As for myself, on this voyage I could scarcely "get a moment to myself" and there was always an accumulation of things to be done, or read, or thought over when a vacant half-hour could be had. The man who will feel true loneliness, is he who has one sailor with him, or a pleasant companion soon pumped dry, for he has isolation without freedom all day (and night too), and a tight cramp on the mind. With a dozen kindred spirits in a yacht, indeed, it is another matter; then you have freedom and company, and (if you are not the owner) you are not slaves of the skipper, but still you are sailed and carried, as passive travellers, and perhaps had better be in a big steamer at once -- the Cunard's or the P. and 0., with a hundred passengers -- real life and endless variety. However, each man to his taste; it is not easy to judge for others, but let us hope, that after listening to this log of a voyage alone you will not call it "lonely."

The Rob Roy is a yawl-rig, so as to place the sailor between the sails for "handiness." She is double skinned to make her staunch and dry below, and she is full-decked to keep out the sea above. She has an iron keel and keelson to resist a bump on rocks, and with four watertight compartments to limit its effects if once stove in. Her cabin is comfortable to sleep in, but only as arranged when anchored for the purpose -- sleep at sea is forbidden to her crew. Her internal arrangements for cooking, reading, writing, provisions, stores, and cargo, are quite different from those of any other yacht, all of them are specially devised, and all well done, and now on the 7th of June, at 5PM she is hastily launched, her ton and a half of pig-iron is put on board for ballast, the luggage and luxuries for a three months' voyage are loaded in, her masts are stepped, the sails are bent, the flags unfold to the breeze, the line to shore is slipped, and we are sailing from Woolwich, never to have any person aboard in her progress but the captain, until she returns to the builders' yard.

Often as a boy I had thought of the pleasure of being one's own master in one's own boat; but the reality far exceeded the imagination of it, and it was not a transient pleasure. Next day it was stronger, and so to the end, until at last, only duty forced me reluctantly from my floating freehold to another home founded on London clay, sternly immovable, and with the quarter's rent to pay. At Erith next day the Canoe Club held its first sailing match, when five little paddling craft set up their bamboo masts and pure white sails, and scudded along in a rattling breeze and twice crossed the Thames. They were so closely matched that the winner was only by a few seconds first. Then a club dinner toasted the prizemen, and "farewell," "Bon voyage" to the captain who retired on board for the first sleep in his yawl.The Sunday service on board the training ship 'Worcester,' at Erith, is a sight to see and to remember. The bell rings and boats arrive, some of them with ladies. Here in the 'tween decks, with airy ports open, and glancing water seen through them, are 100 fresh-cheeked manly boys, the future captains of Taepings and Ariels, and as fine specimens of the gentleman sailor-lad as any Englishman would wish to see. Such neatness and order without nonsense or prim awe. Health and brightness of boyhood, with seamen's smartness and silence, I hope they do not get too much trigonometry. However, for the past week they have been scurrying up aloft "to learn the ropes," skylarking among the rigging for play, and rowing and cricketing to expand muscle and limb, and now on the day of rest they sing beautifully to the well-played harmonium, then quietly listen to the clergyman of the Thames Mission, who has been rowed down here from his floating church, anchored at present in another bay of his liquid parish.

The Royal National Lifeboat Institution had most kindly presented to the Rob Roy one of its best lifeboat compasses. The card of this compass floats in a mixture of spirits so as to steady its oscillations in a boat, and a deft-like lamp alongside will light it up for use by night. Only a sailor knows the peculiar feeling of regard and mystery with which the compass of his craft becomes invested, the companion in past or unknown future perils, his trusty guide over the wide waste of waters and through the night's long blackness. Having so much iron on board, and so near this wondrous delicate needle, I determined to have the boat "swung" at Greenhithe, where the slack tide allows the largest vessels conveniently to adjust their compasses. This operation consumed a whole day, and a day sufficed for the Russian steamer alongside; but then the time was well bestowed, -- it was as important to me to steer the Rob Roy straight as it could be to any Muscovite that he should sail rightly in his ship of unpronounceable name.

"Swinging for the compass" is thus performed: The vessel is moored in the bight at Greenhithe and by means of warps to certain Government buoys she is placed with her head towards the various points of the compass. The bearing by her compass on board (influenced by the attraction of the iron she carries) is taken accurately by one observer in the vessel, and the true bearing is signaled to him by another observer on shore, who has a compass -- out of reach of the "local attraction" of the vessel. The error in each position due to the local attraction is thus ascertained, and the corrections for these errors are written on a card in a tabulated from thus :-

For:

Steer:

And so on. A half point looks a small matter on the compass card, but in avoiding a shoal or in finding a harbour it makes all the difference.

While the compass was thus made perfect for use at one end of the boat her anchors occupied my attention at the other. It was necessary to carry an anchor heavy enough to hold well in strong tides, in bad weather, and through the long nights, so that I could sleep then without anxiety. On the other hand, the anchor must be also light enough to be weighed and stowed by one man, and this too in that precious twenty seconds of time, when in weighing anchor, the boat, already loosed from the ground but not yet got hold of by the sails, is swept bodily away by the tide, and faces look cross from yachts around, being sure you will collide as a lubber is bound to do.

After considering the matter of anchors a long time, and poising too the various opinions of numerous advisers, the Rob Roy was fitted with a 50-lb. galvanized Trotman anchor and 30 fathoms of chain, and also with a 20-lb. Trotman and a hemp cable.

The operation of anchoring in a new place and that of weighing anchor are certainly among the most testing and risky in a voyage like this, where the circumstances are quite new on each occasion, and where all has to be done by one man.

You sail into a port where in less than a minute you must apprehend by one panoramic glance the positions of twenty vessels, the run of the tide, and set of the wind, and depth of the water; and this not only as these are then existing, but, in imagination, how they will be six hours hence, when the wind has veered, the tide has changed, and the vessels have swung round, or will need room to move away, or new ones will have arrived.

These being the data, you have instantly to fix on a spot where there will be water enough to float your craft all night, and yet not so deep as to give extra work next moving, a berth, too, which #1 can reach as at present sailing, and from which you can start again tomorrow; one where there are no moorings of absent vessels to foul your anchor, and where the wind will not blow right into your sleeping cabin when the moonlight chills, and where the dust will not blind you from this lime barge, or the blacks begrime you from that coal brig as you spread the yellow butter on your morning tartine.

The interest felt in doing this feat well is increased by seeing how watchfully those who are already berthed will eye the stranger, often speaking by their looks, and always feeling "hope he won't come too near me;" while the penalty on failure in the proceeding is heavy and sharp, a smash of your spars, a hole in your side, or a sleepless night, or an hour of cable clearing tomorrow, or all of them; and certainly in addition, the objurgations of every yachtsman within the threatened circle.

Undoubtedly the most unpleasant result of bad management is to have damaged any other man's boat and I cannot but mention with the greatest satisfaction that after so often working my anchors -- at least two hundred times -- and so many days of sailing in crowded ports and rivers, on no one occasion did the Rob Roy even brush the paint off any other vessel.

Not far from my yawl there was moored a fine old frigate, useless now for war, but invaluable for peace -- the "'Chichester' Training-ship, for homeless boys of London." It is for a class of lads utterly different from those on the 'Worcester,' but they are English boys still, and every Englishman ought to do something for English boys, if he cares for the present or the future of England.

Pale and squalid, thin, heartless, and homeless, they were; and now, ruddy in the river breeze, neat and clean, alert with energy, happy in their wooden home, with a kind captain and smart officers to teach them, life and stir around, fair prospects ahead, and a British seaman's honest livelihood to be earned instead of the miserable puling beggardom of the streets, or the horrid company of the prison cell, which, that they should lie in the path of any child of our land, adrift on the rough tide of time at ten years old, is a glaring shame to the millions of sovereigns in bankers' books, and we shall have to answer heavily if we let it be thus still longer.*

* The Reformatory ship 'Cornwall' is at Purfleet. The three vessels are within sight of each other. We shall sail back to each of them in a future page, and bare a more leisurely look on board.

The burgee flag of the Canoe Club flew always (white with our paddle across S C in cipher), and another white flag on the mizzenmast had the yawl's name inscribed. Six other gay colours used as occasion required it. These all being hoisted on a fine bright day, and my voyage really begun, the 'Chichester' lads 'boyed' the rigging, and gave three ringing cheers as they shouted, "Take these to France, sir!" and the frigate dipped her ensign in salute, my flag lieutenant smartly responding to the compliment as we bade "good bye."

The Thames to seaward looks different to me every time I float on its noble flood. I have seen it from on board steamers large and small, from an Indiaman's deck, the gunwale of a cutter, and the poop of an ironclad, as well as from rowboat and canoe, and have penetrated almost every nook and cranny on the water, some of them a dozen times, yet always it is new to see.

Thames river life is a separate world from the earth life in houses. The day begins there full an hour before sunrise. Cheery voices and hearty faces greet you, and there seems to be no maimed, or sick, or poor. There is, from the simple fact that you are on the river, a brotherhood with every sailor. The mode is supple as the water, not like the stiff fashion of the land. Ships and shipmen soon become the 'people'. The other folks on shore are, to be sure, pretty numerous, but then they are ashore. Undoubtedly they are useful to provide for us who are afloat the butter, eggs, and bread they do certainly produce; and we gaze pleasantly on their grassy lawns and bushy trees, and can hear the lark singing on high, and peacocks screaming, and all are very pretty, and we are bound to try to sympathize with them, thus pinned to the soil; while we are free in the fine fresh breeze, and glide on the bounding wave. N.B. -- These very people are all the while regarding us with humane pity as the "poor fellows in that little ship there, cabined, cribbed, confined." Perhaps it is well for all of us that the standpoint of each, be it ever so bleak, becomes to him the centre of creation.

As the dullest country-lane has charms for the botanist which will sadly delay one in a summer stroll with such a companion, so to the nautical mind every reach on a full river has a constant flow of incidents quite unnoticed by the landsman. In the crowd of ships around us, no two are quite the same even to look at, nor are they doing the same thing, and there are hundreds passing; what a feast for the eye that hath an appetite! The clink of an anchor-chain, the "yo-ho!" of a well timed crew, the flapping of huge sails -- I love all these sounds, yes, even the shrill squeal of a pulley thrills my ear with pleasure, and grateful to my nostrils is the odour of tar.

Meanwhile we are sailing on to Sheerness, and no wonder that the Rob Roy fixes many a sailor's eye, with the bright sun shining on her new white sails, her brilliant coloured flags fluttering gladly in the wind as the waves glance and play about her polished mahogany sides, the last and least addition to the yacht fleet of England.

Rounding Garrison Point, at the month of the Medway, our anchor is dropped alongside the yacht 'Whisper,' where the kind hospitality to the Rob Roy from English, French, and Belgian at once began, and it ceased only at the end of my voyage.

After our tea and strawberries, and ladies' chat (pleasant ashore and ten times more afloat), the bluejackets' band on board the Guard ship gives music, and the moon gives light, and around are the huge old war-hulks, beautiful, though bygone, and all at rest, with a newer, uglier frigate, that has no poetry in her look, but could speak forth loudly, no doubt, with a very heavy broadside, for her thundering salute shook the windows as she steamed in gallantly.

The tide of visitors to my yawl began at Sheerness. Among them I caught a boy and made him grease the mast. His friends were so pleased with their visit, that when the Rob Roy came there again months afterwards, they brought me a present of fresh mussels, highly to be esteemed by those who like to eat them, everybody does not; but then was it not grateful to give them thus? and is not gratitude a precious and rare gift to receive?

The internal arrangements of the Rob Roy yawl are certainly peculiar, for they were designed for a unique purpose, and as there is no description (at least that I can find) of a yacht specially made for one-man voyages, and proved to be efficient during so long a voyage, it may be useful here to describe the inside of the Rob Roy. Safety was the first point to be attained as we have already mentioned, and this was provided for by her breadth of beam (seven feet), her strongly bolted iron keelson, her watertight compartments, and her double skin, the outer one being of polished Honduras mahogany, and the inner of yellow pine, with canvas between them; also by her strong, firm deck, her undersized masts and sails, and her life-boat dingey.

Next we had to consider the capacity for comfort; not for the sake of any luxurious ease which could be expected, but so as to take proper means to preserve health, maintain good spirits, and to economize the energy which would only be largely taxed in downright physical work, and now would be liable any day if overwrought by long-continued anxiety, wakefulness, and exertion. For this purpose the actual labour bestowed upon maintaining the outward forms of a (partially) civilized life must be a minimum, and the action -- required in times of risk or danger must be as little encumbered as possible; and as every arrangement came frequently under review, and improvements were well considered in meditative hours, and many were put in practice during a stay at Cowes, where the very best workmen were at command, it may not unreasonably be asserted that for a solitary sailor's yacht the cabin of the Rob Roy is at least a very good specimen of the most recent model, and perhaps the best that has been devised as a basis for the next advance. Although at present I have no radical improvements to suggest upon the general plan, it is, of course, open to the refining experience of others, and I do not apologize for speaking of the fittings of a little boat as if they were mere trifles, because it held only one man, when they may in any degree be useful to yachts of larger size, and thus to that noble fleet of roaming craft which renew the nerve and energy of so many Englishmen by a manly and healthful enterprise, opening a whole new element of nature, and nursing a host of loyal seamen to defend our shores.

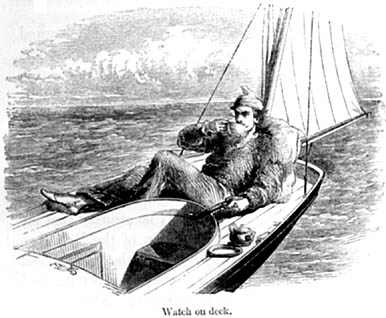

Watch On Deck. [18]

From the sketch given above, and one partly in section at page 39, it will be understood that the Rob Roy is fully decked all over except an open well near the stern, and which is three feet square, and about the same in depth, including a strong combing which surrounds both this well and the main hatchway, as a protection in a sea. The after part of the well is rounded at each side, and it is all boarded up. In the middle is a seat on which a large cork cushion can rest, or this may be thrown over as a life-preserver or for a buoy, while the life-belt to be worn round the waist is stowed away under the seat and an iron basin with a handle is placed alongside it just over the flooring, below which is seen, at page 39, a wedge of lead ballast and in front of this the water well, where water collecting from leakage or dashing spray is conveniently reached by the tube of vulcanized india-rubber represented as just in front. This pump hose has a brass union joint on the top, to which we can screw the nozzle of a pump with a copper cylinder (shown at the bottom), or a piston worked by hand (but without any lever), and when in use the cylinder rests obliquely so that the water will flow out over the combing, and on the deck, and so into the sea. This well or after compartment is separated from the next compartment by a strong bulkhead, which slopes forward so as to give all the room possible for stretching one's limbs and a change of posture, and also so as to form a comfortable sloping back inside in the cabin, which supports a large soft pillow, the whole being used as a sofa to recline on while reading or writing, or finally being converted into a bolster by lowering it when the crew are piped to bed for the night, or at least such hours of it as the tide and wind may allow for sleep.

Fronting the seat the binnacle hangs with its tender thrilling compass inside, well protected by thick plate glass, and the lamp, which is always ready to be lighted up should darkness need it, for experience) has showed me only too plainly that it will not do to postpone any preparation for night, or wind, or hanger, or shoal water, but that you should be always quite prepared for them all.

Above the binnacle is the chart; that is to say a rectangular piece cut out from the larger sheet, and containing all that will be sailed in a day. The other parts, too, of the chart ought to be kept where they are accessible for ready reference.

Rain or the dashing of a wave or two soon softens the paper of the chart, and on one occasion it was so nearly melted away in this manner in a rough sea, that I had to learn its lines and figures quickly off by heart, and trust to memory for the rest of the day.

To prevent another time such an awkward state of things, I made a frame with a glass front and movable hack, and this allowed each portion of the chart to be placed inside, and to be well protected, an excellent arrangement when your hands are as wet as all other things around, and the ordinary chart would be soaked in five minutes.

The chart frame is also detachable from its place, as it is sometimes necessary to hold it near a lamp at night so as to read the soundings. To aid still further to decipher the chart at night and in dull afternoons, there is a small mounted lens in a leather loop alongside, which has often to be used. The compass itself is so placed that you can see it well while either sitting or standing up, or when lying at full length on the deck, with the back against a pillow propped by the mizzen mast, the bright sun or moon overhead, and a turn or two of the mainsheet cast about your body to keep the sleepy steersman from rolling over into the water, as shown at page 18.

This somewhat effeminate but decidedly comfortable attitude in which to keep one's watch on deck, was not invented until farther on in the cruise, and it seems odd that I should so long have continued to sit upright for hours together (wriggling only a little at the constraint) for many a fine day before adopting for a change so obvious a posture, and thus effectually postponing any sense of weariness even in sailing for a whole day and night Still it is only for light airs, gentle waves, or in deep rivers, or with long runs on the same tack, that the captain may do his duty while lie lies on a sofa. In fresh breezes and rolling seas, or in beating to windward with frequent boards, such indulgence is soon cut short, and indeed the muscles and energies of the sailor are so braced up by the lively motion and refreshing blasts when there is plenty of wind, that no ennui can come, and there is quite enough play of limb and change of position caused by the working of the ship, while he soon learns by practice to steer by the action of any part of his body from head to feet being in contact with the tiller, that delicate and true sensorium of a boat to which all feeling is conveyed.

Sometimes I would sit low and out of sight, but with a glance now and then at the compass, while the tiller pressed against my neck. At others I would lie prone on the hatchway with my head upon both hands, and my elbows on the deck, and my foot on the tiller; while, again, every day it was necessary to cook and eat, all the time steering; the most difficult operation of all being to eat a boiled egg comfortably under these conditions, because there is the egg and the spoon, each in a hand, and the salt and the bread, each liable to be capsized with a direful result.

Uncovered and handy for instant use there lies a sharp axe at the bottom of the well, by which any rope may be cut and a blow may be given to the forelock of an anchor or other refractory point needing instant correction, and near this again is the sounding lead, with its line wound on a stick like that of a boy's kite. I soon found that much the best way to tell the fathoms, especially at night, was by measuring the line as it was hauled in by opening my arms to full stretch with one fathom between my two hands.

In two large leather pockets fixed in the well were sundry articles, such as a long knife, cords of various kinds, a foot measure of ivory (best to read off at night) and a good binocular glass by Steward in the Strand. However good the glass, it is very difficult to make use of it for faint or distant objects on the horizon, and on the whole I found it easier to discern the first dim line of land far off by the unaided eye. A slight mark that would not be observed while only a short piece of it is seen in the field of view, becomes decidedly manifest if a large scope is seen at once. The binocular glass was very valuable, however, when the words on a buoy, or the colour on the chequers of a beacon had to be deciphered.

Turning now to the left of the seat in the well, we open a door about a foot square, hinged so as to fall downwards, and thus form a kitchen dresser, and now the full extent is visible of our kitchen range, or in nautical tongue here is the caboose of the Rob Roy.

It is a zinc box with a frame holding a flat copper kettle, a pan in which to heat the tin of preserved meat for our dinner today, and the copper frying-pan in which three eggs will be cooked sur le plat for our breakfast tomorrow.

The invaluable Russian lamp * is below this frame, and a spare lamp alongside -- a fierce blast it has, and it will be needed if there is bad weather, for then sometimes as a heavy sea is coming the kitchen is hastily closed lest the waves should invade it but the lamp may be heard even then roaring away inside all the same. An iron enamelled plate and a duster complete the furniture of our little scullery; all the rest of the things we started with having been improved out of existence; for simplicity is the heart of invention, as brevity is the soul of wit.

If we desire to get at the tubular wooden flag box that some gay colours may deck our mast in entering a new harbour, this will be found inside the part (at F in the sketch), and again, by reaching the arm still further into the hollow behind our seat it will grasp the storm mizzen, a strongly made triangular sail (at S), to be used only in untoward hours, and for which we must prepare by lowering the lug mizzen, and shifting the halyard, tack, and sheet. Then the Rob Roy (the mainsail and jib being reefed), will be under snug canvas, as seen at page 57. But now it is bedtime, and the lecture on the furniture of the yawl may be finished some other day.

* See Appendix.

CHAPTER II.

Sheerness -- Governor -- Trim -- Earthquake -- Upset -- Wooden legs -- On the Goodwin -- Cuts and scars -- Crossing the Straits -- The ground at Boulogne -- Night music -- Sailors' maps -- Ship's papers -- Weather -- Toilette -- Section

SHEERNESS is on the whole a tolerable port to land at, that is, as long as you refrain from going ashore. The harbour is interesting and more lively than it appears at first sight, but the streets and shops are just the reverse.

The Rob Roy ran into this harbour seven or eight times during her cruise, and there was always "something going on." The anchorage on the south of the pier is in mud of deep black colour, but not such good holding ground as it would seem to be, and then what comes up on the anchor runs like black paint upon your deck, and needs a good scrubbing to get rid of it from each palm of the anchor. Even after all seems to be cleared away thoroughly, there may be a piece only the size of a nut, but perverse enough to fasten upon the white creamy folds of your jib newly washed out, and then the inky stain will be an eyesore for days, until, for peace of mind, the sail must be scrubbed again. Trifles these are to the yachtsman who can leave all that to his crew, who sees only results, but the realities of sea life are what must be endured as well as enjoyed when the captain alone is the crew, and yet surely he is the one to enjoy most keenly the luxury of a white spotless sail when his own hands have made it so.

If any sailor henceforth has me for his captain, and he has to "tidy up" my yacht, he may be sure of having a very considerate if not indulgent master -- " Governor," of course, I mean, for there are no "masters" any longer now, they are all promoted to the rank of "Governor."

And the reason I should be considerate is that until you do it all yourself you cannot have any idea of the innumerable minutiae to be attended to in the proper care of a yacht. Mine, indeed, was in miniature, but the number of little things was still great, though each little thing was more little. On the whole, we should say that a yacht's crew, even in port, have full employment for all their working hours if the hull, spars, sails, ropes, and boats, besides the cabin and stores, are always kept in that condition of order, neatness, cleanliness, readiness, and repair which ought to be little short of perfection when regarded with a critical eye.

In like manner as you drive out in a carriage and return, and the carriage and horses disappear into the stables for hours of careful work by the men who are there, so may the day's sail in a yacht involve a whole series of operations on board afterwards. Inattention to these in the extreme can be observed in the boats of fishermen, and attention in the extreme in the perfect vessels of the Royal Squadron; but even a very reasonable amount of smartness requires a large expenditure of labour which will not be effectual if it be hurried, and which is, of course, worse than useless if it is done by inferior hands.

In perfect trim and 'ship shape' now, we loosed from Sheerness, to continue the sail eastwards, and with a leading breeze, and a lovely morning. This part of the Thames is about the best conjunction of river and sea one could find, with land easily sighted on both sides, yet flue salt waves, porpoises, and other attributes of the sea, and buoys, and beacons, and lightships to be attended to, and a definite line of course determined on and followed by compass. A gale here is riot to be trifled with, though in fine weather you may pass it safely in a mere cockleshell, and the last time I had sailed here alone it was in an open boat, just ten feet long inside. Still the whole day may be summed up now, as it was in the log of the Rob Roy "Fine run to Margate;" the pleasures of it were just the same as so often afterwards were met, enjoyed, and thanked for, but which might be tedious to relate even once.

The harbour here dries bare at low tide, and as seventeen years had elapsed since we had sailed into it, this bad habit of the harbour was forgotten, but mere years than that may pass before it will be forgotten again, for as evening came, and the water ebbed, and I reclined unharnessed in the cabin, reading intently, there suddenly came a rude bumping shove upwards as from below, and then another -- the Rob Roy had grounded. Soon there was a swaying this way anti that, as if yet undecided, and at length it positive heel ever to that; the whole of my little world within being canted to half a right angle, and it ridiculous distortion of every single thing in my bedroom was the result. The humiliating sensation of being aground on hard unromantic mud is tempered by the ludicrous crooked appearance of the contents of your cabin, and by tine absurd sensation of sleeping in a corner with everything askance except the lamp flame, which, because it burns upright, looks most awry of all, and incongruously flames on the spout of the teapot in your pantry.

And why this bouleversement of all things? Because I had omitted to bring a pair of legs with me, for a boat cannot stand upright on shore without legs any more than an animal.

Next time the Rob Roy came to Margate we made one powerful leg for her by lashing the two oars to the iron shroud, and took infinite pains to incline the boat over to that side, so as to be turned away from the wind and screened from the tide, and I therefore weighted her down by placing the dingey and heavy anchor on the lee gunwale, and then with misplaced contentment proceeded to cook my dinner. At a solemn pause in the repast the yawl, without other warming than a loud splash, perversely turned over to the wrong side, with deck to sea and wind, and every single thing exactly the contrary of wheat was proper. I had just time to plunge my hissing spirit-lamp into the sea, and thus to prevent the cry of "Ship on fire!" but had not time to put out my cabin lamp, and this instantly bore its flame provokingly upright against the thick glass of the aneroid barometer, which duly told its fate by three sonorous "crinks," and at once three starred cracks shot through its crystal front. The former experience of the night as spent when one is thus arbitrarily "inclined to sleep," made me wish to get ashore; but this idea was stifled partly by pride, and partly by the fact that there was not water enough to enable me to go ashore in a boat, and yet there was too much water besides soft mud to make it at all pleasant to set off and wade to bed. The recovery from this unwholesome state of things, with all the world askew, was equally notable, for when the tide rose again, in the late midnight hours, the sea-dreams of disturbed slumber were arrested by a gentle nudge, and then by a more decided heaving up of one's bed in the dark, until at last it came level again as the boat floated, and all the things that were right when she was wrong turned over now at wrong angles, because the boat had righted.

In yet another, the fourth visit to this stupid shallow harbour (one of the most unpleasant to lie in anywhere), I fixed an oar out at each side as a leg, and could scarcely get rest from the fear that one or other of my beautiful oars would be snapped as they bent acid groaned with remonstrances against supporting several tons of weight in the capacity of a wooden leg. An excellent cure for all such little mishaps is to "imagine it is tomorrow morning," for in the morning one is sure to forget all the night's troubles, and so with the fiery rising sun on the sails we are floating down to Dover.

In such a sunny day the North Foreland is a very comfortable-looking cliff, with pleasant country-houses on the top, and cornfields growing round the lighthouse. Next there is Ramsgate, and then Dover pier. But now, and in weather hike this, will be a proper occasion to practise manoeuvres which will certainly have to be performed in bad times, so we stretched away out to the Goodwin Sands, where one is nearly always sure to find a sea running, and for several hours we worked assiduously at reefing the sails, and getting the little dingey out of the cabin and into the water, and vice versa.

At least a short trial of my yacht in the Thames would have been advisable before starting on a long voyage, but as this was not possible now, it was of invaluable benefit to spend an afternoon at drill on the Goodwin; rightly assured that success in this journey could not be expected haphazard, but might be hoped for after the practice in daylight and fine weather of what had to be done afterwards in rough water and darkness.

By this time, just a week in the Rob Roy, the little craft seemed quite an old friend. Her many virtues and her few faults were being found out. The happy life aboard had almost enchained me, but still I left the yawl at Dover, and ran up to London for the annual inspection of the London Scottish Volunteers; and having led his fine company of kilted Riflemen through Hyde Park, the Captain sheathed his claymore to handle the tiller again, eager for the voyage.

The new rough hairy ropes had chafed my hands abundantly, and they were red and black, and blistered, and variously adorned by cuts, and bruises, and sears. When shall I ever get gloves on again, or be fit to appear at a dinner table? These wounds, however, had taught me this lesson, "Do every act deliberately. Hasty smartness is slowest. When each single thing from morning to night has to be done by your own fingers, save them from bruises and chafes. Nothing is worse spent than needless muscular action. You will want every atom you have some day or other this week. Husband vital force."

The Sappho schooner was at Dover, and her owner, Mr. Lawton, one of the Canoe Club, took leave of the Rob Roy, and sailed away to Iceland, while I started for Boulogne in the dawn, when all the scene around looked hike a woodcut, pale and colourless, as I cooked hot breakfast at five o'clock. Nothing particular happened in this voyage across the Channel. It was simply a very pleasant sail, in a fine day, and in a good little boat. The sight of both shores at once, when you are in the widest part of a passage, removes it immediately from the romance and interest of being entirely out of sight of land and of ships, and of all else but water, and so there is absent that deeper stir of feeling which powerfully seized me in the wide traverse afterwards from Havre to Cowes.

Indeed, when you know the underwater geography of the channel near Dover, it is impossible not to feel that you are sailing over shallow waves; for though they seem to be deep and grand enough from Dover Castle or the Boulogne heights, the whole way might almost be spanned by piers and arches, and if you wished to walk over dry shod at the low spring-tide, you need only lay from shore to shore a twenty miles' slice of undulated ground cut from the environs of London. The cellars of the houses would be at the bottom of the sea, but the chimney-pots would still be above it for steppingstones.

The wind fell as we neared France, and a fog came on, and the tide carried us off in a wrong direction north to Cape Grisnez, where I anchored with twenty fathoms, to wait for the reflux six or seven hours. Often as we had to do the same thing in after days, there was always constant employment for every hour of a long stoppage like this, with a good toolbox, a busy mind, ever making additions, experiments, improvements, and with books to read. Not one single moment of the voyage ever hung heavy in the Rob Roy.

Trying to get into Boulogne at low water was an unprepared attempt, and met its due reward; for the thing had to be done without the benefit of my "Pilot-book," which had been put away with such exceeding care, that now it could not anywhere be found -- not after several rigorous searches all over the boat. Finally concluding that I must have taken the book to London by mistake, we had to trust to nature's light and go ahead. This does well enough for a canoe, but not for the sailing-boat which, if once aground, and with a sea running, it would be utterly out of the power of one man to save.*

In encountering the first roller off the pier at Boulogne, she thumped the ground heavily. At the second, again, the masts quivered, and all the bottles rattled in my cellar. Instant decision turned her round from the third roller, and so, after bumping the ground twice again in the retreat, we put out to sea, anchored, and got out the dingey, half-ashamed to be discomfited thus at the very first French port.

* I had lessened her ton and a half of iron ballast by leaving two hundredweight on Dover quay; good advice agreeing with my own opinion that the Rob Roy was needlessly stiff.

After an hour or two spent in the dark, carefully sounding to discover and trace the proper channel and to get it well into my head, the anchor was weighed, and we entered in a poor sort of berth about midnight, slowly ascending the long harbour, but looking in vain for a proper berth. All was quiet, every one seemed to be in bed, until I came to the sluices at the end, which just then opened, and the rush of foaming water from these bore me back again in the most helpless plight until I anchored near the well-known "Etablissement," furled sails, rigged up hatch, and soon dropped fast asleep.

Now there is a peculiarity of the French ports which we may mention here once for all, but it applies to every one of them, and has to be seriously considered in all your calculations as a sailing master.

They are quiet enough up to a certain time of night, but as the tide serves, the whole port awakes, all the fishing vessels get ready to start. The quays become vocal with shouts, yells, calls, whistles, and the most stupid din and hubbub confounds the night, utterly destructive of sleep. This chorus was in full cry about two o'clock A.M. Soon great luggers come splashing along with shrieks from the crews, and sails flapping, chains rattling, spars knocking about, as if a tempest were in rage. Several of these lubberly craft smashed against the pier, and the men screamed more wildly, and at length one larger and more inebriated than all the rest, dashed in among the small boats where the Rob Roy slept, and swooping down on the poor little yawl, then wrapt in calm repose, she heeled us over on our beam-ends, and then fastening her clumsy, rusty anchor in my mizzen shrouds (which were of iron, and declined to snap), bore me and my boat away far on; ignominiously, stern foremost.

Certainly this was by no means a pleasant foretaste of what might be expected in the numerous other ports we were to enter, and, at any rate, that night's sleep was gone. But in a voyage of this sort a night's sleep must be resigned readily, and the loss is easily borne by trying to forget it, which indeed you soon do when the sun rises, and a good cup of tea has been quaffed, or, if that will not suffice, then another. Vigorous health is at the bottom of the enthusiastic enjoyment of yachting, but in a common sailor's life sleep is not a regular thing as we have it on shore, and perhaps that staid glazy and sedate-looking eye, which a hard-worked seaman usually has, is really caused by broken slumber. He is never completely awake, but he is never entirely asleep.

Boulogne is a much more agreeable place to reside at than one might suppose from merely passing through it. Once I spout a month there, and found plenty to see and to do. Good walks, hotels, church, and swimming-baths. The river to row in, the reading-room to sit in, the cliffs to climb, and the sands to see.

At Dover the dock-people had generously charged me 'nil' for dues. I had letters for France from the highest authorities to pass the Rob Roy as an ''article entered for the Paris Exhibition" and when the douane and police functionaries came in proper state at Boulogne to appraise her value, and to fill up the numerous forms, certificates, schedules, and other columned documents, I had hours of walking to perform, and most courteous and tedious attention to endure, and then paid for sanitary dues, two sons per ton, that was threepence. Finally, there was this insurmountable difficulty, that though all my ship's papers were en règle, they must be signed "by two persons on board," so I offered to sign first as captain and then as cook. They never troubled me again in any other port, probably thinking the boat too small to have come from a foreign harbour. In France the law of their paternal Government prevents any Frenchman from sailing all alone.

The sun warmed a fine fresh breeze from the N.E. as we coasted from Boulogne, and to sail with it was a luxury all day. First there was the morning ablution, either by a wholesale dip under the waves, or a more particular toilette, if the Rob Roy was then in full sail.

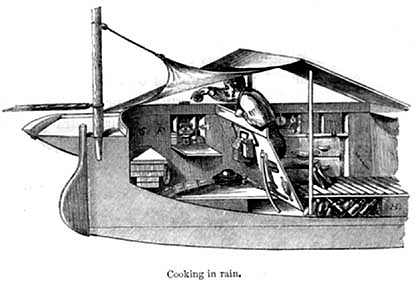

Cooking in Rain. [39]

To effect this we push the hatch forward, and open the interior of the boat. If the water is clean, either salt or fresh, we dip the tin basin at once, but if in a muddy river or doubtful harbour we must draw from the zinc water tank, which is on the left side, and holds water for one week. This tank is concealed by the figure of the cook in the sketch, but it is next to my large portmanteau in the lower shelf.

A large hole in the top of the tank allows it to be filled at intervals through a tundish, and a long vulcanized tube through the cork to the bottom has an end hanging over. When I wish to draw water it is done by applying the mouth for a moment with suction, and the clear stream then flows by syphon action into a strong tin can of about eight inches cube, which holds fresh water for one day. By means of this tube, the end of which hangs within an inch or two of my face when in bed, I can drink a cool draught at night without trouble or chance of spilling a drop. On the tank top is soap, and also a clean towel, which to-morrow will be degraded into a duster, and 'relegated,' the newspapers would say, to the kitchen, and from whence it will again be promoted backwards over the bulkhead to the washing-bag. This you see is the red-tape order of dealing with towels on board the Rob Roy.

On the left shelf of the cabin we find two boxes of japanned tin each about eighteen inches by six inches wide, as shewn in the woodcut. Below the shelf is a portmanteau full of clothes. One of the boxes holds "Dressing," another "Reading and Writing." The aneroid barometer, and my watch are seen suspended alongside. The boxes on the other side, shewn in section at a future page, are marked "Tools" and "Eating," while the pantry is beside them, with teapot cup (saucer discarded), and tumbler; and a tray holding knife and fork, spoons, salt in a snuffbox (far the best cellar after trials of many), pepper (coarse, or it is blown away), mustard, corkscrew, and lever-knife for preserved meat tins, &c., &c.

The relative positions of all these articles had been maturely considered and carefully arranged, and they were much approved by the most experienced and critical of the many hundred visitors who inspected the Rob Roy.

The north coast of France from Boulogne to Havre is well lighted at night, but the navigation is dangerous on account of the numerous shoals and the tortuous currents and tides. For about the first half of the distance the shores are low, and the water, even far out, is shallow. Afterwards the land rises to huge red cliffs, rugged and steep sometimes for miles, without any opening.

The real matter of importance, however, in coasting here is the direction of the wind. Had it been unfavourable, that is S.W., and with the fogs and sea which that wind brings, it would have been a serious delay to me-perhaps, indeed, a stopper on my voyage -- as I had sometimes to enter a port at night so as to to sleep in peace, which could scarcely be pleasantly done if anchored ten miles from land, and with no one awake to keep a lookout. Fortunately we had good weather on the worst parts of the French coast, and my stormy days were yet to come.

© 2000 Craig O'Donnell

May not be reproduced without my permission.