THE

VOYAGE ALONE

IN THE

YAWL "ROB ROY,"

By JOHN MACGREGOR, M.A.

CHAPTER III.

Russian lamp -- Breakfast -- Store rooms -- Mast-light -- Run down -- Rule of the road -- Signal thoughts -- Sinking sands -- Pilot caution -- French coast

AFTER a wash and morning prayers the crew are piped to breakfast, so we must now turn to the kitchen, which after constant use some hundred times I cannot but feel is the most successful "hit" in the whole equipment.

Much thought and many experiments were bestowed on this subject, because, first, it was well known that the hard and uneven strain of bone, muscle, and energy in a voyage of this sort needs to be maintained by generous diet, that cold feeding is a delusion after a few days of it, and that the whole affair would fail, or at any rate, enjoyment of the trip would cease, unless the Rob Roy had a caboose, easy to work, speedy in result, and capable of being used in rain, wind, and rough weather, and by night as well as by day.

Of course, all stoves with coal or coke, or similar fuel were out of the question, being hard to light, dusty when lighted, and dirty to clean. Various spirit lamps, Etnas, Magic stoves, Soyers, and others, were examined and tried, and all were defective in grand points.

The Russian lamp, used in his Alpine climbs by Mr. Tuckett, who occupies the distinguished office of "Cook of the Canoe Club," was found far superior to all these. This lamp (see the Appendix) is less than three inches each way, and has no wick, but acts after the manner of a blowpipe. In two minutes after lighting it pours forth a vehement flame about a foot in height, which with a warming heat boils two large cups full in my flat copper kettle in five minutes, or a can of preserved meat in six minutes.*

While the kettle is boiling we bring forward the box marked "Eating," take the loaf of bread out of its macintosh swathing, prepare the egg pan with two eggs, the teapot, and put sugar

*In the sketch at page 39, the cook is represented as he works when rain compels him to shelter himself in the cabin under a tarpaulin, and the hatch inclined upwards. But usually -- indeed, always but on two occasions-he sat in the well while he tended the caboose.

into the teacup, and a spoonful of preserved milk (Amey's is most convenient, being in powder; but Borden's, in a kind of paste, is most agreeable); lastly, we overhaul the butter tin and pot of marmalade or anchovies.

The healthful relish with which a plain hot breakfast of this sort is consumed with the fresh air all round, and the sun athwart the east, and the waves dancing while the boat sails merrily all the time, is enhanced by the pleasure of steering and buttering bread, and holding a hot egg and a teacup, all at once.

Then, again, there is the satisfaction of doing all this without giving needless trouble in cleaning up, for every whit of that work, too, is to he yours. A crumb must not fall in the boat, because you will have to stoop down afterwards and pick it up, seeing that whatever happens, one thing is insisted on -- "the Rob Roy shall be always smart and clean."

All the breakfast things are cleared away and put by, each into its proper place, and a general "mop up" has effaced the scene from our deck, but we can still take a look below and notice what is to be seen.

Some of the articles chiefly important in the well of our boat have been already described, but only those on the left of the steersman sitting.

Now, turning to the right we find a watertight door, like that on the opposite side, to be opened by folding down, and it reveals to us, first the "Bread store," a fourpenny loaf wrapped in macintosh, which makes the best of table cloths, as it may be laid on a wet deck, and can be washed and dried again speedily; next there is a butter keg (as in the coolest place), and a box of biscuits, and a flask of rum-the "Storm supply" -- only to be drawn upon when things of air and sea are in such state that to open the main hatch would be questionable prudence.

Here are, also, ropes, blocks, and purchases, as well as a fender, not to keep coals on the hearth, but to keep the mahogany sides of the Rob Roy safe from the rude jostlings of other craft coming alongside. Above these odds and ends is the "Spirit room," a strong reservoir made of zinc, with a tap and screw plug, and internal division, not to be rendered intelligible by mere description here, but of important use, as from hence there is served out, two or three times, daily, the fuel which is to cook for the whole crew. One gallon of the methylated spirits, costing four shillings and sixpence, will suffice for this during six weeks.

Above the spirit room will be found a blue light to be used in case of distress, and a box of candles, so that we may be enabled to rig up the mast-light if darkness comes, when it will not do to open the cabin. This ship-light is therefore carried here. It is an article of some importance, having to be strong and substantial, easily suspended and taken down, and one that can be trusted to shew a good steady light for at least eight hours, however roughly it may be tossed about when you are fast asleep below, in the full confidence that nobody who sees your mast-light will run his great iron bows over your little mahogany bedroom. Yet I rear it does not do to examine into the grounds for any such confidence. Many vessels sail about in the dark without any lights whatever to warn one of their approach, and not a few boats, even with proper lights in them, are accidentally run over and sunk even in the Thames; while out at sea, and in dark- drizzly rain or fog, it is more than can be expected of human nature that a "lookout man" should peer into the thick blackness for an hour together, with the rain blinding him, and the spray splash smarting his eyes, and when already he has looked for fifty-nine minutes without anything whatever to see. It is in that last minute, perhaps, that the poor little hatch-boat has come near, with the old man and a boy, its scanty crew, both of them nodding asleep after long watches, and their boat-light swinging in the swell. There is a splash, a crash, and a spluttering, and the affair is over, and the dark is only the dark again. Nobody on the steamer knows that anything has occurred, and only the fishermen to-morrow on some neighbouring bank will see a broken bull, floating sideways, near some tangled nets.

I fully believe that more care is taken for the lives of others by sailors at sea than in most cases on land where equal risks are run, hit there are dangers on the waves, as well as on the hills, the roads, and even in the streets, which no foresight can anticipate, and no precaution can avert.

The principal danger of a coasting voyage, sailing alone, is that of being run down, especially on the thickly traversed English coast, and at night.

As for the important question concerning the 'rule of the road' at sea, which is every now and then raised, discussed, and then forgotten again after some collision on a crowded river in open day has frightened us into a proper desire to prevent such catastrophes, it appears to me that no rule whatever could possibly be laid down for even general obedience under such circumstances without causing in its very observance more collisions than it would avert, unless the traffic in the river were to be virtually arrested.

On land the "rule of the road" is well enough on a road, but how would it do if it were to be insisted upon in every street? Now the Thames and other populous rivers are at times as much blocked and crowded by the craft that sail and steam on the water as Ludgate Hill is by vehicles at three o'clock, that is, considering fairly the relative sizes of the objects in motion, and the width of the path they must take, their means of stopping or steering, and, above all, the great additional forces on the water which cannot be arrested-wind and tide. The wonderful dexterity of the cabmen, carmen, and coachmen of London is less wonderful than that of the men who guide the barges, brigs, and steamers on the Thames, and it is perfectly amazing that huge masses weighing thousands of tons, and bristling with masts and spars, and rugged wheels projecting, should be every day led over miles of water in dense crowds, round crooked points, along narrow guts, and over hidden shoals, while gusts from above, and whirling eddies below, are all conspiring to confuse the clearest head, to baffle the strongest arm, and to huddle up the whole mass into a general wreck.

Consider what would be the result in the Strand if no pedestrian could stop his progress within three yards, but by anchoring to a lamp post and even then swinging round with force. Why, there would be scarcely a coal-heaver who would not be whitened by collision with some baker's boy. Ladies in full sail would be run down, and dandies would be sunk by the dozen.

That there should be so many collisions in the open sea is strange, but that so few take place with serious damage in the Thames, the water street of the world, is far more wonderful. We may learn, too, lessons from land for safe traffic on water The cabman who "pulls up" is sure to signal first with his whip to the omnibus astern of him, and the coachman who means to cross to the "wrong side" never does so without a warning to those he is bearing down upon. What is most wanted, then, on the water, is some ready, sure, and costless signal, to say, "I am going to break the rule;" for nearly all collisions are caused by one ship not being able to know what the other is going to do. This is my thought on the matter after many thoughts and some experience: meantime while we have ate, and talked and thought, our yawl has slipped over six miles of sea, and we must rouse up from a reverie to scan the changing picture.

Glance at the barometer-note the time. Trim the sails, and bear away to that pretty fleet of fishing boats bobbing up and down as they trail their nets, or the men gather in the glittering fish, and munch their rude breakfasts, tediously heated by smoky stoves, while they gaze on the white-sailed stranger, and mumble among themselves as to what in the world he can be. The sun mounts and the breeze presses till we are at the bay of the Somme, with its shifting sands, its incomprehensible currents, and its low and treacherous coast, buoyed and beaconed enough to puzzle you right into the shoals. The yacht with my friend S---- in her, bound for Paris, has just been wrecked we hear-unpleasant news now-on that bank near Cayeux, and there is St. Valery, from whence King William the Conqueror sailed with his fleet for England, as may be seen on the curious tapestry at Bayeux worked by his Queen's hands, and still almost as fresh as them I never saw a place look so perfectly different from sea and from land as this strange port, so I ran in just to reconnoitre, and spent some hours with chart, compass, lead-line, and Pilot-book, trying my best to make out the currents, but all to no purpose, except to conclude that a voyage along this coast in bad weather would be madness, unless with a man to help.

But nearly all this part of the French coast is awkward ground to be caught in, especially where there are shifting or sinking sands, for if the vessel touches these, the tide stream instantly sucks the sand from under one side, while it piles it up on the other, and thus the hull is gradually worked in with a ridge on each side, and cannot be slewed off, but is liable to be wrecked forth with. The following paragraph was interesting to read here in my Pilot-book, which I had at length dug out of its hiding-place.

"Caution. -- During strong winds between W.S.W., round westerly, and N.N.W., the coast to the eastward of Ailly Point is dangerous to be on, and shipwrecks are of frequent occurrence ; vessels therefore of every description at that period should keep a good offing, and when obliged to approach it, must do so with great caution; for although the general mass of the above banks appear to be stationary, yet great attention must be paid to the lead, and in observing the confused state of the sea in the various eddies, so as to guard against suddenly meeting with dangers which may be of recent formation. The lights for the purpose of pointing out the position of the headlands and dangers between Capes Antifer and Gris-Nez at night, are so disposed, that in clear weather two can always be seen at a time, and the greater number of the harbours have one or more tide-lights shown during the time the harbour can be entered.

"It is important to notice that along the coast, between Cape de la Hève and the town of Ault, (a space of 67 miles), the wind, when it blows in a direction perpendicular, or nearly so, to the direction of the coast, is reflected by the high cliffs, neutralizing in great measure its original action to a certain extent in the offing, depending upon the strength of the wind. It follows from this, that a zone is formed off the coast and parallel to it (except in front of the wide valley; where the direct wind meets with no obstacle, where the wind is light the sea much agitated, and the waves run towards the shore. On the contrary, when the wind ferns an acute angle with the coast, the reflected wind contributes to increase the direct wind near the shore."

CHAPTER IV.

Thunder -- In the squall -- The dervish -- Sailing consort -- Poor little boy ! -- Grateful presents -- The dingey's mission -- Remedy -- Rise and work

THE aneroid barometer in my cabin pointed to "set fair" for many a day, and just, too, when we required it most to be fine, that is along the French coast. Had the Rob Roy encountered here the sort of weather she met with afterwards on the south coast of England, we feel quite assured she must have been wrecked ashore or driven out to sea for a miserable tinier

So it was best to keep moving on while fine weather lasted, for there was no knowing when this might change, even with the wind as now in the good N.E. The Pilot-book says (page 3), "Gales from N. to N.E. are also violent but they usually last only from 24 to 36 hours, and the wind does not shift as it does with those from the westward. They cause a heavy sea on the flood stream, and during their continuance the French coast is covered with a white fog, which has the appearance of smoke. This is also the case with all easterly winds, which are sometimes of long duration, and blow with great force."

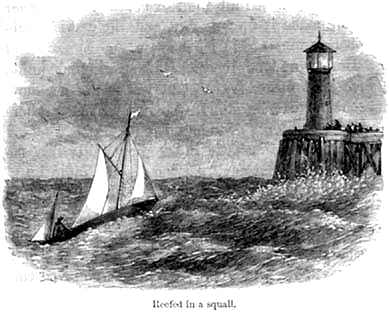

In the evening, as a soft of practical comment on the text above, there was a sudden fall of the wind, and then a loud peal of thunder. Alert in a moment, we noticed, far away in the offing, the fishing-boats dip their sails and reef so we knew there would soon be a blow, and we resolved to reef, too, and just in time. My life-belt, therefore, was soon strapped on, and two reefs put in the mainsail and one in the jib, and the storm mizzen was set, all in regular order, when up sprung a fine west breeze, just as we were opposite Treport, a pretty little bathing town under some cliffs, where my night-quarters were to be.*

*As a precaution, I always put on the life-belt when I bad to reef, as one is liable then to be jerked overboard; Also in strong winds when we ran before them, because in case of getting overboard then, it would be difficult to catch the yawl by swimming; also at night when sailing, or when sleeping on deck, as one might then be suddenly run down. But with all this prudence it happened that on each of the three occasions when I did fall into the water, I had not the life-belt on. The Life-Boat Institution had presented to me one of their life jackets--an invaluable companion if a long immersion in the water is to be undergone. Rut for convenience in working the ropes and sails I was content to use the less bulky lifebelt. It is conveniently arranged, and you soon forget it as an encumbrance Indeed on one occasion I walked up to a house without recollecting that my life-belt was upon me when ashore!

The book already referred to gave a rather serious account of the difficulties of entering Treport, its shingle bar, and the high seas on it and the cross tide and exceedingly narrow entrance; but in an hour more the Rob Roy had conic close to all these things, and rose and fell on the rollers chasing each other ashore.

The points to be kept in line for entering the harbour were all clearly set forth in the book, and the flags and signals on the pier were all faultlessly given, while a crowd gradually collected to see the little boat run in, or be smashed, and it was rather exciting to feel that one bump on the bar with such a sea, and -- in two minutes she would be a helpless wreck.

Among the spectators, the only one who did not hold his hat on against the wind, was an extraordinary personage who capered about shouting. Long curly hair waved over his face; his dress was hung round with corks and tassels; he swung a long lifeline round his head, and screamed at me words which were of course utterly lost in the breeze.

This dancing dervish was the "life saver," marine preserver, and general bore of the occasion, and he seemed unduly annoyed to see me profoundly deaf to his noise as I stood on the afterdeck to get a wider view, holding on by the mizzenmast, steering with my feet, and surveying the entrance with my glass. All the people ran alongside as the Rob Roy glided past the pier and smoothly berthed upon a great mud bank exactly as desired, and then I apologised to the quaint Frenchman, saying that I could not answer him before, for really I had enough to do to steer my boat, at which all the rest laughed heartily, but we made it up next day, and the dervish and Rob Roy were good friends again.

Here we found the 'Onyx,' an English built yacht, but owned by M. Charles, one of the few Frenchmen to be found, who really seems to like yachting; plenty of them affect it.

He was enthusiastic in his hospitality, and I rested there next day, meeting also an interesting youth, an eager sailor, but who took sea trips for his health, and drove from some Royal Chateau to embark and freshen the colour in his delicate face, so pale with languor We could not but feel and express a deep sympathy with one who loved the sea, but was yet in such contrast to the rough brown hue and redundant health enjoyed so long by myself.

All was ataunt again, and then the two yachts started in company for a run to Dieppe, which is only about thirteen miles distant. We came upon a nest of twelve English yachts, all in the basin of this port, so my French comrade spent the rest of his time gazing at their beauty, their strength, their cleanliness, and that unnamed quality which distinguishes English yachts and English houses, a certain fitness for their Special purpose. These graceful creatures (is it possible that a fine yacht can be counted as an inanimate thing?) reclined on the muddy bosom of the basin, but I would not put the Rob Roy there, it seemed so pent up and torpid a life, and with the curious always gazing down from the lofty quay right into your cabin, especially as next day I wished to have a quiet Sunday. Instead of a peaceful day of rest the Sunday at Dieppe was unusually bustling from morning to night, for it was the "Fete Dieu" there. The streets were dressed in gala, and strewed with green herbs, while along the shop fronts was a long festooned stripe of white calico, set off by roses here and there; the shipping, too, was decked in flag array, and guns, bells, and trombones ushered a long procession of schools and soldiers, and young people coming from their first communion, and their priests, and banners, and relies which halted round temporary altars in the open air, to recite and chant, while a vast crowd followed to gaze.

In a similar procession at St. Cloud, one division of the moving host was of the tiniest little children, down to the lowest age that could manage to toddle along with the band of a mother or sister to help, and the leader of them all was a chubby little boy, with no head gear in the hot sun but his curly hair, and with his arms and body all bare, except where a lambskin hung across. He carried a blue cross, too, and the pretty child looked bewildered enough. Some thought he was John the Baptist, many more pronounced it a 'bottise.'

In the canoe voyages * of the two preceding summers, I bad found much pleasure and interest in carrying a supply of books and periodicals, and illustrated stories in various languages, which were given as occasion admitted to all sorts of people, and everywhere accepted with thanks, so that we could only regret the limit imposed on the number to be carried in a canoe, where every ounce of weight added to the muscular toil.

Relieved now from the restriction, the Rob Roy yawl was able to load in its cargo several boxes of Testaments, books, periodicals, pictures, and interesting papers, in different tongues, and most of them kindly granted for the special purpose of this voyage by the publishers, or Societies whence they are issued.

* The account of these paddlings has been published in 'A Thousand Miles in the Rob Roy Canoe,' 5th edition, and in 'The Rob Roy in the Baltic,' 2nd edition, both works being profusely illustrated (Low, Son, and Marston, Ludgate Hill).

These were given away from day to day, and especially on Sunday afternoons, among the sailors and water-population wherever the Rob Roy roved. Thousands of seamen can read, and have time, but no books. Bargees lolling about, or prone in the sun, eagerly began a 'Pilgrim's Progress' when thus presented, and sometimes went on reading and thinking for hours. Fishermen came off in boats to ask for them, policemen and soldiers too, begged for a book, and then asked for another for a child at school.' Smart yachtsmen were most grateful of all, and some even offered to pay for them; the navvies, lock-keepers, ferrymen, watermen, porters, dock-men, and guardmen of light houses, piers, and hulks, as well as many a Royal Navy bluejacket, gratefully accepted these little souvenirs with every appearance of gratitude.

The distribution of these was thus no labour, but a constant pleasure to me. Permanent and positive good may have been done by the reading of their contents;' at any rate, they opened up conversation, gave scope to courteous intercourse, often leading to kinder interest. They opened to me many new scenes of life, and some with darker passages and sorrowful groups in the evident but untold background. They were, in fact, the speediest possible introductions by which to meet at once with large bodies of fellow men too much unknown to us, therefore forgotten, and then despised. The strata of society are not to be all ground into a pulpy mass, but a wholesome mingling betimes does good, both to heavy dregs, below and the me on the very top.

Thus encouraged, we launch the little dingey on Sunday for three or four hours' rowing, and with a large leather bag well filled at starting, but empty on its return; and instead of its contents we bring back in our memory a whole series of tales, characters, and incidents of watercraft life, some tragic, others comic, many 'humdrum' enough, but still instructive, suggestive, branching out into hidden lives one would like to draw forth, and telling Sorrows that are softened by being told. Of the French crews I began with here, not one of the first few could even read, while five or six English steamboats took books for all their men. On a preceding Sunday (at Erith), I did not meet one man, even a bargee, who could not read, and all up the Seine only one in this predicament. Truly there is a sea-mission yet to be worked. Good news was told on the water long ago, and by the Great Preacher from a boat.

And while thus giving these books and papers to others, it may perhaps be allowed us also to add a few reflections suggested on returning from the scenes and people we have sailed amongst abroad. New scenes ought to be to the mind what fresh air is to the body, reviving it for work as well as gladdening it with play; and perhaps one can do more for human misery by withdrawing now and then from its close contact, than by constant action in its midst. Yet it must be admitted that the first impressions on one's return from such a vacation as the Rob Roy had are painfully acute. To come back and read up in an hour the diary of the three months' work of our "Boy's Beadle" (the agent employed by the reformatory Union to look after and attend to the uncared-for street children), is to resume one's post of contemplation of the dreadful picture of woe which crowds an endless canvas with suffering figures, and each case delineated in such a report means far more behind to the eye that can realise. Again, to walk past St. George's Hospital next day and observe the stream of visitors with anxious steps going up the stairs, and those coming down with kind and thoughtful looks, as they leave their dearest relatives, and confidingly, in strangers' hands, and to think what is up there. To find in letters awaiting one's return the gaps made by death in the circle of acquaintances. These are salutary but sudden shocks to self enjoyment of health and whole limbs, and they are loud calls for more than a gush of sympathy or a song of thankfulness, but for downright help by practical work. Still greater was the change from hounding along in flushed health on merry waves of the wholesome sea, to a walk through the east end of London-that morass or vice, and sighs, and savagery--what is forced on the senses in an hour being not a hundredth of what is sunk below.

Perhaps it is well we do not always realize the amount of evil around us, of bad, I mean, that can be made good by efforts, some of which we are bound to make. If we knew how big the mountain is we might despair of digging it down by spadefuls, though the faith that digs is the one that can say with best hopes for obedience, "Be thou removed and cast into the sea." Few children would have courage to begin the alphabet as a step to learning if they knew what a long and heavy road is to be trudged beyond.

And it may be remarked that in returning to one's post of duty after a time of "leave," there is at first a disposition rather to generalize about what ought to be done than to set to work and do it.

It is natural that before putting on the harness once more we should take a look at the collar and buckles, and at the load to be drawn, and it may be allowable to the soldier, while on his way to rejoin the ranks to take just a glance at the line of march before he falls in. Theorizing is soon cut short, however, by the clamour of work waiting to be done, and the absorbing interest felt in doing it, and perhaps too soon we forget all doubts as to whether the direction of our labours is after all the best, or whether time might not be saved by improving the instruments of our work, the object of using them being still the same.

Now there is a reflection suggested each time in frequent foreign travel which lasts longest on my mind after returning to England-" How is it that our lowest classes seem to be lower than the lowest abroad?"

Whether they are so or not is another question, but in all our great towns there is a mass of human beings whose want, misery, and filth are more patent to the eye, and blatant to the ear, and pungent to the nostrils than in almost any other towns in the world. Their personal liberty is greater, too, than anywhere else. Are these two facts related to each other? Is the positive piggery of the lowest stratum of our fellows part of the price we pay for glorious freedom as guaranteed by our "British Constitution"? and do we not pay very dearly then? Must the masses be frowsy to be free?

The highest class of society enjoy the benefits of our mode of government; rank and wealth secured, and prestige far above that of many of the sovereigns swept away lately by Bismarck's besom. In return they surrender only the pleasure of downright tyranny and a small quota of their ample gold.

The middle class can also enjoy their freedom from oppression, and a nominal share in politics, and they pay by hard work for this.

But the wretched beings at the bottom of all, muddled, starved, and squalid, cannot enjoy freedom, and we cannot permit them to have "license." They seethe by thousands in ignorance and foulness , and with our "British Constitution" standing by in all its glory they rot and perish, a multitude dark and unclean.

Our advances in legislation of late are prodigious, but chiefly aid the two classes above these. If the policeman stationed in a crowded street has now power to stop this carriage, and hasten on that cart, it does far more for cart and carriage than for the limping foot passenger who waits to cross between. If our factory masters must now send their children to school, it will better the busy artisan, but not the street Arab. That all the luxury and congestion of wealth in the head of the body corporate, while its lowest limbs arc in rags and pallid mortification, should be permitted by the one, blinded by plethora, and peacefully endured by the other, dispirited by inanition, and with such few twinges of pain through the vital parts, is an astounding marvel; but it may cease any day-if not the permission, then the endurance will cease. If the rich are not mingled with the wretched they are at least entangled with them, and by knots that cannot be untied and will not be cut. The thief indeed, and the burglar, and more lately the lazy vagabond, have forced us to consider them; and we even attend to the drunkard, provided he pleads for notice by rolling in our path. Perhaps at last the wretched also will arrest us. Is not the time come yet to rouse up head, and heart, and hand, to do more than we have attempted, and to raise at the least the appearance of our lowest classes to the respectability now attained in countries we are apt to despise?

What is the specific? I have no new one, and no new reasons for the old one, except to repeat how well it works when it is directly applied. It is easy enough to find tools to work with in this field, if only we are persuaded that work has to be done and are willing to take our share. Numbers do this, and nobly; and much is done, but not half enough. Thousands are yet idle here, who will not listen to God or their conscience or even their instinct in the matter, who live comfortably apart from the evil places, and hear only now and then a message from the dying wafted on the sable wings of cholera or typhus. It is these, who are moved neither by religion nor humanity, that a good scolding may stir up; and if we can show them that the state of our lowest classes is a national disgrace that we are beaten as in a battle and distanced in a race, then they will soon find the means by which national honour is to be retrieved. Half-a-dozen Englishman are in danger of death in Africa, and we spend three millions of money because they are Britons, and to sustain the British name; but thousands are living in wretchedness or dying in misery, Britons all the same, almost at our doors, but, not seen, and less heard of than if they were in Abyssinia, and to leave them as they now are is a scandalous national disgrace, which every true Englishman who knows the facts is ashamed of and which, even if he is ignorant of them at home, he is forced to feel abroad by the taunts of strangers.

Already we wonder that we ever kept the Thames as a common sewer; others will wonder, some day, that their fathers had a great human sink in every great town reeking out crime, disease, and disloyalty on the whole nation. I have seen the serfs in Russia, the slaves in Africa, and the negroes in America; but there are thousands of people in England in a far worse plight than these--their very nearness to light, and happiness, and comfort makes their misery more unbearable.

National honour may be a lower motive to work upon than love to Christ or love to man; but it works in larger numbers than either of these, and on a scale large enough to remove a national disgrace which will cling to the nation until the nation rises to shake it off.

CHAPTER V.

Cool -- Fish wives -- Iron-bound coast -- Etretat -- Ripples -- Pilot Book -- Hollow water -- Undecided -- Stomach law -- Becalmed -- Cape la Hève -- The breeze -- Havre de Grace -- Crazy

So much for Sunday thoughts; but after the day had ended, there happened to me an absurd misery, of the kind considered to be comical, and so beyond sympathy, but which must be told in my Sunday log.

The little yawl being anchored in the harbour bad also a long rope to the quay, and by this I could draw it near the foot of an upright ladder of iron bars fixed in the stones of the quay wall, an ordinary plan of access in such cases. The pier-man promised faithfully to watch my boat as the tide sunk (it was every moment more and more under his very nose), and so to haul her about that she should not "ground" before my return; yet when I came back at night, her keel had sunk and sunk until it reacted the bottom, so she could not be moved with all our pulling. Moreover the tide had gone out so far as to prevent any boat at all from coming to the dock wall round the harbour. I tried to amuse myself for all hour while the tide might rise; but at length, impatient and sleepy and ready for bed, to be off to-morrow at break of day, I determined to get on board at once somehow or other.

Descending then by the iron bars until I reached the last of them, I swung myself on the slack of the strong cable hanging from above (and attached at the other end to my yawl), and which the man received strict orders to "haul taut" at the critical moment Alas! in his clumsy hands the effect intended was exactly reversed; the rope was gently loosened, and I subsided in the most undignified, inevitable, and provokingly cool manner, quietly into the water at 10:30 P.M. However, there was no use in grumbling, so I spluttered and laughed, and then went to bed.

Long before sunrise the Rob Roy was creeping out of the harbour of Dieppe against the strong wind at that point dead ahead; but I took the towline thrown down from the quay by some sturdy fishwives, who will readily tug a boat to the pier head for a franc or two, and thus save a good half hour of tedious rowing against wind and tide. This rope was of a deep black colour, very fine, thin, and yet strong. There was no time to find out what it was made of but it seemed to be plaited of human hair. As I was aft in my boat and steering, the line suddenly slipped and disappeared, and the Rob Roy was in great danger of going adrift on the other pier head, but the excellent dames speedily regained their long black tress, and coiled it and threw it to me again with great dexterity; and soon all was put right, and the sails were up, and the line cast off, and we plunged along in buoyant spirits.

It was a fair wind now, and with a long day in front and the freshness of Monday after a good rest. Still this was a rather more anxious day than the others, because while the coast of the Somme had dangers, they were hidden by water; and on a sunny morning who can realize shoals that are so fatal in bad weather, but are concealed by the smiling calm of a fine day? Not so with the great beetling cliffs of sharp red flint now glittering alongside my course for miles and miles far beyond what the eye could reach. These formed an impressive object ever in sight, and generally begetting, as it was seen, an earnest hope that the weather might be good just today. This part of the coast, too, besides being iron-bound, has no port that is easy to enter, and the tides moreover are very powerful, so that, with either a gale or a calm, there would be a danger to meet.

It is obvious, of course, to the sailor who reads this that the difficulty of navigation along this coast was much increased by my being alone. An ordinary vessel would put well out to sea, and go on night and day in deep water with a good offing, and its crew would take watch and watch till they neared the land again close to their destination.

But the course of the Rob Roy had to be within seven or eight miles of the shore, so as to be within reach of a port at night, or at the worst near some shallower spot for anchorage; else, in the attempt to sleep, I might have been drifted twenty miles by the tide, perhaps out to sea, right away from our course, and perhaps ashore on the rocks. It bad not yet become my plan to pass whole nights at sea as was necessary in the latter part of this Voyage. With these little drawbacks now and then, which threw rather a graver tone into the soliloquy of the lonely traveller; it was still a time of excessive enjoyment The noble rocks towered up high on the left, and the endless water opened out wide on the right with some dot of a sail, hull down, far far off on the horizon, which looked a lonely speck fixed in hard exile; but very probably the crew in that vessel too were happy in the breezy morn, and felt themselves and their craft to be the very "hub of the universe."

In a nook of the cliffs was Etretat, now the most fashionable bathing-place of Northern France. Long pointed pillars of rock stood in the sea along this shore, one especially notable, and called the "Needle of Etretat." Others were like gates and windows, with the light shining through. I thought of looking in here to escape the flood-tide which was against me, but was deterred by the Pilot-book telling in plain words, "The Eastern part of the beach at Etretat is bordered by rocks which uncover at low water."

The Rob Roy's behaviour already in a sea made me quite at ease about waves or deep water; but to strike on a rock would be a miserable delay, and somehow I became more cautious as to exposing my little craft to danger the more experience I acquired; certainly also she was valued more and more each day. This increase together of experience and of admiration, begetting boldness and caution by turns, went on until it settled down into this compromise--extreme care in certain circumstances, and perhaps undue boldness in all besides.

All over the British Channel there are patches of sand, shingle, or rock, which being deep down are not dangerous as regards any risk of striking upon them, but still they cause the tide-stream even without any wind to rush over them with great eddies, and confused babbling waves. The water below is in action, just like a waterfall tumbling over a hill, and the whirlings and seethings above look threatening enough until you become thoroughly aware of the exact state of the case, being precisely that which occurs above Schaffhausen, on the deeps of the Rhine, and which we have described in the account of a canoe voyage there.

These places are called by the French "ridèns," or in England "ridges," and in some charts, "overfalls," and while there is sure to be a short choppy sea upon them, even in calm weather, the effect of a gale is to make them boil and foam ferociously.

A somewhat similar feature is the result when a low bank projects under water from a cape round which the tide is rushing; and as I determined not to risk going into Etretat, we had to face the tedious tossing off one of these banks, described thus in the Pilot-book :-

"Abreast Etretat the shoal bottom, with less than eight fathoms on it, projects a mile to the N.N.W. from the shore, and when the flood-stream is at its greatest strength it occasions a great eddy, named by the mariners of the coast the Hardières, which extends to the northward as far as the Vaudieu flock, and makes the sea hollow and heavy when the wind is fresh from the eastward."

It was just because the wind was fresh from the eastward that I could hope to stem the tide and get through this place; but once in the middle of the hubbub, the wind went down almost to nothing, so that for three or four hours I could only hold my place at most, and the wearisome monotony here of "up and down" on every wave, with a jerk of all my bones each time, was one of the few dull and disagreeable things of the whole voyage.

A sea that is "hollow" is abominable. However high a wave is, it may still have a rounded and respectable shape, and it will then tilt you about smoothly; but a "hollow" sea merely splashes and smacks and twists and screws, and the tiring effects on the body, thus hit right and left with sudden blows, is quite beyond what would be anticipated from so trifling a cause. At length, as the tide yielded, the wind carried me beyond the Hardières, on and on to Fécamp where the Rob Roy meant to stop for the night.

But, willing though I was to rest there, the appearance of Fécamp from the offing was by no means satisfactory. It did not look easy to get into, and how was I to get out of it to-morrow ? The Pilot-book took a similar view of this matter saying :-

"Fécamp harbour is difficult to enter at all times, and dangerous to attempt when it blows hard from the westward on account of the heavy sea at the entrance; for should a vessel at that time miss the harbour and ground upon the rocks off Fagriet Point, she would be totally lost."

Yet I must put in somewhere, and this was the nearest port to the Cape Antifer, the only remaining point to be anxious about, and which we might now expect to round next day. On the other hand, there was the argument, "If the wind chops round to the west, we may be detained in Fécamp for a week, whereas now it is favourable; and if we can possibly get round today -- Well what a load of anxiety would be tumbled off if we could do that!" The thought, quite new, seemed charming, and, yet undecided, I thought it best to cook dinner at once and put the question to the vote at dessert.

It is very puzzling what name to give to each successive meal in a day when the first one has been eaten at 2 A.M. If this is to be considered as breakfast, then the next say at nine o'clock, ought to be "lunch," which seems absurd, though the Americans call any supplemental feeding a lunch, even up to eleven o'clock at night, and you may see in New York signboards announcing "Lunch at 9 P.M. Clam Chowder."*

Now, as I had often to begin work by first frying at one or two o'clock in the moonlight, and as it would have a greedy sound if the next attack on eatables were to be called "second breakfast," because it was later; the only true way of settling this point was to consider the early meal to be in fact a late supper, or at any rate to regard it as belonging to the day bygone, and therefore beyond inquiry, and so to ignore this first breakfast altogether in one's arrangements, The stomach quite approved of this decision, and was always ready for the usual breakfast at six or seven, whatever had been discussed a few hours before.

* A mysterious shellfish delicacy.

The matter as to Etretat was decided then. We two were to go on, and hope the wind would do so too. Then away sped we merrily singing, with the new and unexpected prospect of possibly reaching Havre that very day. From thence a month was to be passed in going up and down the Seine and at Paris; and what was to come after that? How come back to England? Why that must now be "blinked," as a future, if not an insoluble question, at any rate just as easy to solve a month hence as it is now.

For a long time the wind was favourable, and precisely as strong as was desirable, and the formidable looking Cape Antifer, which at midday seemed only a dark blue stripe on the distant horizon, gradually neared us till we could see the foam eddying round its weather-wasted base. Then came the steep high wall of flint cliff with shingle débris at its foot, but no one approach from top to bottom, if any bad thing happened-no, not for miles.

This was a time of alternate hope and fear, as We wind gradually lulled away to nothing, and fog arose in the hot sun; the waves were tossing the Rob Roy up and down, and flapping the sails in an angry petulant way, very distressing if you are sleepy, For four hours this hapless state of things continued, yet we were already within four or five miles of Cape de la Hève and once round that, on the other side was Havre. How tantalizing to be so near; and yet still out of reach! If this calm ends in a west wind, we may be driven back anywhere by that and the tide. If it ends in a thunder storm we shall have to put off to sea at once.

See there the lighthouses up aloft on the crag -- two of them are lighted. Soon it will be dark around, and we shall have at least to enter Havre by night All this time we were close to the cliffs, but the sounding-lead showed plenty of water; and when the anchor was thrown out the cable did not pull at all; we were not drifting, but only rocked by the incessant tumble and dash of the sea, which, though of all things glorious when careering in the breeze, is of all most tiresome when rolling in a calm.

At this time I felt lonely, exceedingly lonely and helpless, also sleepy, feverish, discontented, and miserable. The lonely feeling came only twice more in the voyage; the other bad feelings never again.

Now, there are one or two sensations or perceptions which after experience at sea seldom deceive you as to what they prognosticate, though it is impossible to give reasons for their bold upon the mind. One is the feeling, "I am drifting," another, "The water is shoaling," and the third, "Here comes a breeze," Each of these may be felt and recognised even with your eyes shut. It does not come through one sense or another; but seems to grasp the whole system; and it is a very great convenience to have this faculty alive in these three directions, and to know when to trust it as a true impression.

On the unmistakable sensation that a breeze was coming, the rebound from inaction and grumbling, lying full-length on deck, to alert excitement was instantaneous and most pleasing. The anchor was rattled up in a minute, and it was scarcely stowed away before the genial air arrived, with ripples curling under its soft breath, and once more exactly favourable.

Slowly the two lights above on the cliff seemed to wheel round as we doubled the Cape. Slowly two little dots in the distance swelled up into big vessels in full sail, and others rose from the far off waters, all converging to the same port with myself; their very presence being companionship, and their community of purpose begetting a mutual interest. For these craft deep in the water the navigation here is rather intricate, though the excellent and uniform system of buoys employed in France does all that is possible to make the course clear, but my little boat, drawing less than three feet of water, could run safely even over the shallows, though as a rule I navigated her by the regular channels, as this gave me much additional interest in the bearings about every port.

When the lights at Havre hove in sight the welcome flashing was a happy reward to a long day's toil, and as the yawl sped forward cheerily through the intervening gloom, the kettle hummed over the lamp, and a bumper of hot grog was served out to the crew. Soon we rounded into the harbour, quiet and calm, with everybody asleep at that late hour; and it was some time more before the Rob Roy could settle into a comfortable berth, and her sails all made up, bed unrolled, and the weary sailor was snoring in his blanket.

Next day the people on the quays were much amused by the curious manoeuvres of my little dingey. Its minute size, its novel form (generally pronounced to be like a half walnut-shell), its bright colour; all varnished mahogany, and the extraordinary gyrations and whirlings which it could perform, for practice taught some new feat in it almost every day.

At night there was a strange sound, shrill and loud, which lasted for hours, and marred the calm and the quiet twinkling of the stars. It was some hundred children collected by a crackbrained stranger (said to be English). These he gave cakes and toys to by day lavishly, and assembled them at night on the quay to sing chorus to his incoherent verses -- a proceeding quite wonderful to be permitted by the police so strict in France.

© 2000 Craig O'Donnell

May not be reproduced without my permission.