THE

VOYAGE ALONE

IN THE

YAWL "ROB ROY,"

By JOHN MACGREGOR, M.A. CHAPTER VI.

The Seine -- A wetting -- Pump -- Locks -- Long reach -- Rouen -- Steering -- A mistake -- Horny hands -- Henpecked -- British flag -- The captain's wife

HAVRE was a good resting-place to receive and send letters, read up the newspapers, get a long walk, and a hot bath, and fresh water and provisions. Bacon I found, after many trials to cook it, was a delusion, so I gave mine to a steamboat in exchange for bread. Hung beef too was discovered to be a snare--it took far too long to cook, and was tough after all; so I presented a magnificent lump to a bargee, whose time was less precious and his teeth more sharp. Then one mast had to come down in preparation for the bridges on the Seine; and therefore with these things to do, and working with tools and pen, all the hours were busily employed until, at noon on June 26, I hooked on to a steamer, 'Porteur,' with its stern paddles (very common in France), to be towed up the river; a long and troublesome of 300 miles, so winding is the course to Paris by the Seine.

This mode of progress was then new to me, and I had made but imperfect preparations, so that when we rounded the pier to the west, and met the short, snappish sea in the bay, every wave dashed over me, and in ten minutes I was wet to the skin, while a great deal of water entered the fore-compartment of the yawl through the hole for the chain-cable at that time left open. The surprising suddenness of this drenching was so absurd that one could only laugh at it, nor was there time to don my waterproof suit-the sou'wester from Norway ten years ago, the oilskin coat (better than macintosh) from Denmark last year, and the canvas trowsers.

A good wetting can be calmly borne if it is dashed in by a heavy sea in honest sailing, or is poured down upon one from a black cloud above; but here it was in a mere river-mouth, and on a sunny day, and there was no opportunity to change for several hours, until we stopped at a village to discharge cargo. The river at that place is~ narrow, and all the swell I thought was past; so, after a completes change of clothes, it was too bad to find in a mile or two the same story over again, and another wetting was the result. The evening rest was far from comfortable with my bedding all moist, and both suits of clothes wet through. One has therefore to beware of the accompaniments of being towed. The boat has no time to go over the waves, and, long rope or short, middle or side, steering ever so well, the water shipped when a heavy boat is swiftly to wed has to be as well prepared for as if it were a regular gale in open sea.

The Rob Roy had now in the hold a great deal of water; and for the first time I had to ply the pump, which, having been carefully fitted, acted well. An india-rubber tube leading down to the keel was in such a position that I could immediately screw on a copper barrel and work the piston with one hand, so as to clear the stern compartment. By turning a screw-valve I could let the water come from the centre compartment, if any was there, and then I went to the fore-compartment, about seven feet long, which held the spare stores, and a curiosity in the shape of a regulation chimney-pot hat to be worn on state occasions, but which was brought out once a week merely to brush off the green mould.

Much water had entered there through the hole in deck for the chain-cable, but good thick paper had fortunately preserved a number of French Testaments from being spoiled.

At noon the steamer set off again, dragging the yawl astern, and soon entered the first lock on the Seine, where the buildings around us, the neat stone barriers, and the dress and very looks of the men forcibly recalled to my mind the numerous locks passed in my canoe trips, but in so different a manner, by running the boat round every one of them on the gravel or over the grass:

The waste of time in passing through each lock was prodigious. In nearing it the steamer sounded her shrill whistle to give warning, but the lock was sure to be full of barges and boats when we came close. Then our cavalcade had to draw aside until the sluggish barges in front had all come out, and we went into the great basin with bumps, and knocks, and jars, and shouting. It required active use of the boathook for me to get the Rob Roy into the proper place in the lock, and then to keep her there. The men were not clumsy nor careless, but still the polished mahogany yawl had no chance in a squeezing match with the heavy floats and barges, and it was always sure to go to the wall.

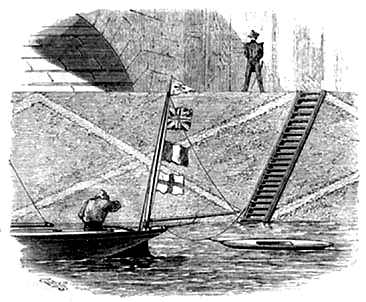

The sailors and dockmen were eager for my cargo of books; and among the various odd ways by which these had to be given to men on large vessels, there is one shown in the sketch alongside, where the cabin-boy of a steamer looking through the round deadlight with an imploring request in his face, stretched out an eager hand to catch the book lifted up on the end of one of my sculls.

Time seemed no object to these people, they were no doubt paid by the day. The sun shone, and it was pleasant simply to exist and to loiter in life, so why make haste?

Finally we ascended as the lock filled, and then a second and a third joint cut off from our too long tail of barges had to be passed in also. After all, the captain and sometimes the whole crew deliberately adjourned to the lock-keeper's house for a "glass" and a chat; and when that was entirely (lone, and every topic of the day discussed, they came back and had another supplemental parliament on the steamer's deck like ladies saying "good bye" at a morning visit; so that, perhaps, in an hour from beginning it, the work of ten minutes was accomplished, and the engine turned again once more-a tedious progress.

Thus it was that four nights and part of five days were passed in mounting the Seine.

The scenery on the banks is in many places interesting, in a few it is pretty, and it is never positively dull. The traffic on the river is considerable above Rouen; but as there are two railways besides, few passengers go by water, and the carriage of heavy goods to and from the Exhibition must have been a principal item in the steamer's work this year. But the architecture and engineering on this fine river are indeed splendid. The noble bridges, the vast locks, barrages, quays, barriers, and embankments are far superior to ours on the Thames, though that river floats more wealth in a day than the Seine does in a month.

Then the neatness and apparent cleanliness of the villages, and the well-clothed well-mannered people-these all so "respectable." France is progressing by great leaps and bounds at least in what arrests the eye.* Its progress in government, liberty, and politics, is perhaps rather like that in a waltz.

*Yet, putting Russia and Spain aside as yet savage, the latest statistics (October, 1867) shew France to be the lowest in education in Europe.

Life in a towed yacht, alone on the Seine, is a somewhat hard life. First you have to be alert and steer for sometimes twenty hours a day, and to cook and eat while steering. At about three o'clock in the morning the steamer 5 crew seemed suddenly to rise from the deck by magic, and stumble over coal-sacks, and thus abruptly begin the day. We stopped about nine o'clock at night, and the crew flopped down on deck again, asleep in a moment, but not I for an hour or two.

As the grey dawn uncovered a new and cloudless sky, the fierce bubblings in the boiler became strong enough to turn the engine, and our rope was slipped from the bank. Savoury odours from the steamer soon after announced to me their breakfast cooking, and the Rob Roy's lamp too was speedily in full blast. Eggs or butter or milk were instantly purveyed, if within reach at a lock; sometimes delicious strawberries and other fruits or dainties, the only difficulty was to cook at all properly while steering and being towed.

It is easy to cook and to steer at sea without looking up for many minutes. The compass tells you by a glance, and if not the tiller has a nudge which speaks to the man who knows the meaning of its various pressures, through any part of his body it may happen to touch. But if you forget to steer constantly and minutely in a heavy boat towed on a river, she swerves in an instant, and shoots out right and left, and dives into banks or trees, or into the steamer's side-swell, and the man at the wheel turns round with a courteous French scowl, for he feels by his tiller in a moment, and you cannot escape his rebuke.

There was no romance in this manner of progress up the river. The poetry of wandering where you will, and all alone, cannot be thrown around a boat pulled by the nose while your are sitting in it all day. The Rob Roy, with mast down, and tied by a towrope, was like an eagle limping with clipped pinion and a chained foot. Still, for the man not churlish, there is scarcely any time or place or person wholly devoid of interest, if he is determined to find it there.

The steamboat captain and crew were chatty enough, and when we towed a string of barges the yawl was lashed alongside of one of these (and not at the end of the line), so that I visited my fellow travellers, soon became friends, and then interchanged presents. All this of the sailor was far better done by the French bargee than in England.

In both countries they frequently mistook me at first for a common sailor in charge of a yacht for my dress told no more. As intercourse proceeded it was curious to watch the gradual recognition of the fact that the sailor talked and thought not just the same as others. Then they regarded me as an agent come to sell the pretty boat; but it was in England only that any of them could be made to believe that the owner of the Rob Roy "would not part with his boat did not want a cook or cabin-boy, and was not at all anxious to see the end of his voyage." Gradually the conversation, begun as between equals, would sometimes decline till the word "Sir" was sprinkled over it; and once or twice-and this not in France-it came to that "glass of beer," sheepishly enough asked for, which of course instantly drowns the converse that has been free on one side and independent on the other.

"Workmen," "working men," "artisans," or whatever they are, or whatever you may call them, mean the class now being spoiled by petting in England-let them be told (perhaps it maybe said plainest by their best friends) that there are just as many proud exclusives among them as in any other stratum of society, and that there is at least a frill share of conceit foppery, and affectation.

It may be heresy to say so, but the "horny hand" has no necessary connection whatever with the "honest heart," as is the fashion to say on one side, and almost to believe on the other; and the friend who really does shake that hand with a brotherly feeling is the most likely and the best entitled to refuse to talk popular nonsense of this sort about the "people."

For that night we stopped usually in towns, but once or twice in a great bend of the river where the steamer was run straight into the trees fast ashore exactly as if it were on the Mississippi and not on the Seine.

That thousands of solitary fishermen should sit lonesome on the river was the same puzzle to me as it had been before in canoeing on other French streams. Their silence and patience, during hours of this self-inflicted isolation, were incredible for Frenchmen, fond as we at first think all of them to be of "billard," café, or dancing puppies, of anything, in fact, provided it assumes to be lively.

One thing I am at last decided about, that it is not to catch fish these men sit there; and the only reasonable explanation I can find of the phenomenon is that all these meek and lone fishermen are husbands unhappy at home!

There are numerous sailing boats and rowing boats on the Seine; but I did not see one that there was any difficulty in not coveting-their standard of marine beauty is not ours. All rigs and all sizes were there, even to a great centre board cutter, twenty-five feet broad, and any number of yards long, in which the happy yachtsman could sail up and down between two bridges which bounded him on either side to a two miles' reach!

The French national flag is perhaps the prettiest on the world's waters; but as it is repeated to the eye by every boat and building its sight becomes tiresome, and suggests that absence of private influence and enterprise so striking to an Englishman in every French work. Then again their sailors (not to say their landsmen) in very many instances do not even know our English flag when they see it, our union-jack or ensign widely unfolded on every shore.

At first I used to carry the French flag as well as our British jack out of compliment to their country, but as I found out that even in some of their newspapers the Rob Roy was mentioned as a " beautiful little French yacht," I determined that that mistake at any rate should not be fostered by me, so down came the tricolour, and my Cambridge Boatclub flag took its place. In one reach of the river we came upon a very unusual sight for a week day, a French boat sailing. Her flag was half-mast high, and she was drifting down the stream a helpless wreck. A distracted sort of man was on board, and a lady, or womankind at least, with dishevelled locks (carefully disordered though), the picture of weary wretchedness, and both of these entreated our captain to tow the little yacht home.

But, after a knowing glance, he quickly passed them in silence, and another steamer behind us also rounded off so as to give the unhappy pair the widest possible berth. Perhaps both captains preferred English sovereigns to French francs. I was charged about 3£. for being towed to Paris, but the various steamers (six in all) I employed on the river were every one well managed, and with civil people on board. Indeed, I became a favourite with one captain's wife, a sturdy-looking body, always cutting up leaves of lettuce. She gave me a basin of warm soup, and I presented her with some good Yorkshire bacon. Next day she cooked some of this for me with beans, and I returned the present by a packet of London tea, a book, a picture of Napoleon, and another of the Rob Roy on the Seine, in the highest style of art attainable by a man steering all the time he is at the easel. Often it was necessary to restrain the inquisitive French gamins, who would teaze a boat to pieces if not looked after, but it is always against the grain to be strict with boys especially about boats, for I hold that it is a good sign of them when they relish nautical curiosities.

CHAPTER VII.

Dull reading -- Chain boat -- Kedging -- St. Cloud -- Training -- Dogs -- Wrong colours -- My policeman -- Yankee notion -- Red, White, and Blue

THE effect of living on board a little boat for a month at a time with not more than three or four nights of usual repose, was to bring the mind and body into a curious condition of subdued life, a sort of contemplative oriental placid state in which both cares and pleasures ceased to be acute, and the flight of time seemed gliding and even, and not marked by the distinct epochs which define our civilised life. Although this passive enjoyment was really agreeable-and, in fine weather and good health, perhaps a mollusc could affirm as much of its existence -- certainly an experience of the condition I have described enables one to understand what is evidently the normal state of many thousands of hard-worked, ill-fed, and irregularly sleeped labourers; the men who, sitting down thus weary at night, we expect to read some prosy book full of desperately good advice, of which one half the words are not needed for the sense and the other half are not understood by the reader.

Very few authors can write books suitable for men with weary bodies and sleepy minds. It is remarkable to see how much attention these men will pay to the words of the Bible and the' Pilgrim's Progress.'

No doubt such readers often read but the surface sense of both these books; but then even this sense is good, and the deeper meaning is better, while the language of both is superb.

The last tugboat we had to use was of a peculiar kind, and I am not aware that it is employed upon any of our rivers in Britain. A chain is laid along the bottom of the Seine for (I think) two hundred miles. At certain hours of the day a long solidly built vessel with a powerful engine on board comes over this, and the chain is seized and put round a wheel on board. By turning this wheel one way or the other it is evident that the chain will be wound up and let down behind, while it cannot slip along the river's bottom-the enormous friction is enough to prevent that, and therefore the boat is wound up and goes through the water. The power of this chain-boat is so great that it will pull along, and that too against the rapid stream, a whole string of barges, several of them of 300 tons' burthen, while the long fleet advances steadily though slowly, and the irresistible engine works with smokeless funnels, but with groanings within, telling of tight-strained iron, and loud undertoned breathings of confined steam.

Although the chain-boat is not often steered for the purpose of avoiding other vessels (they must take care of their own safety), yet it has to be carefully managed by a rudder, one at each end, so that it may drop the chain in a proper part of the river for the next steamer of the Company which is to use it. When two such boats meet from opposite directions, and both are pulling at the same chain, there is much time lost in effecting a passage, and again when the chain-boat and all its string of heavy craft arrives at a look, you may make up your mind for a long delay. It is evident that we do not require this particular sort of tugboat on the Thames below Teddington. The strong tide up and down twice every day carries thousands of tons of merchandize at a rapid pace, and needing but one or two men to attend upon each barge. In fact we have the sun and moon for our tugs. They draw the water up, and the tide is the rope which hauls our ships along.

To manoeuvre properly with the Rob Roy in such+ a case as this with the chain-boat required every vigilance, and strong exercise of muscular force, as well as caution and prompt decision, for I had sometimes to cling to the middle barge, then -to drop back to the last, and always to keep off from the riverbanks, the shoals, and the trees. On one occasion we had to shift her position by "kedging" for nearly half a mile, and this in a crowded part of the Seine too, where the current also was swift. On another occasion the sharp iron of a screw steamer's frame ran right against my -bow, and at once cut a clean hole quite through the mahogany. Instantly I seized a lump of soft putty, and leaning over the side I squeezed it into the hole, and then" clinched "it (so to speak) on the inside; and this stopgap actually served for three weeks, until at proper repair could be made.

The lovely precincts of St. Cloud came in sight at dawn on the last day of June, prettier than Richmond, I must confess, or almost any river town we can boast of in England; and here I was to rest while my little yawl was thoroughly cleaned, brightly varnished, and its inside gaily painted with Cambridge blue, so as to appear at the French Exhibition in its very best suit and then at the British Regatta on the Seine. Some days were occupied in this general over- haul, during which the excellent landlady of the hotel where I slept must have been more amazed at this even than she declared, to see her guest return each day clad in blue flannel, and spattered all over with varnish and paint for the captain was painter as well as cook. Of course all this was exchanged for proper attire after working hours.

In the cool of the morning, three fine young fellows are running towards us over the bridge; lithe and easy step, speed without haste. White flannel and white shoes. They have come to contend at the regatta here, the first of an invasion of British oarsmen, who soon fill the lodgings, cover the river, and waken up the footpath in the mornings by taking their early run. Some are brown-faced watermen from Thames and Humber and Tyne, others are ruddy-cheeked Etonians or University men, or hard-trained Londoners, and others have come over the Atlantic; John Bull's younger brothers from New Brunswick, not his cousins from New York. You might pick out among these the finest specimens of our species, so far as pluck and muscle make the man.

Few of the French oarsmen could be classed with any of the divisions given above. Rowing has not attained the position in France which it holds in England. For much of our excellence in athletics and field sports we have to thank our much-abused English climate, which always encourages and generally necessitates some sort of exercise when we are out of doors.

But it is a new and healthy sight ~ these fine fellows running in the mornings, and it gives zest to our walk by the beautiful river.

Here also as we stroll about, two dogs gave much amusement to us; one was a Newfoundland who dashed into the water grandly to fetch the stick thrown in by his master. The other was a bulldog, who went in about a yard or so at the same time, and then as the swimmer brought the stick to shore the intruder fastened on it, and always managed somehow to wrest the prize from the real winner, and then carried it to his master with the cool impudence which may be seen not seldom when the honour and reward gained by one person are claimed and even secured by another.

Very many phases of human character may be studied among dogs. If men's vices are matched by dogs' failings, several of our best virtues are at least equalled by those in canine characters; courage, fidelity, and patience especially. One might well devote at whole hour in London to observe the dogs in the streets -- to look at doglife solely, and forget all besides; and it would be both an interesting and instructive time. It is hard to believe (even if indeed we are at all warranted in believing) that these noble animals are done with existence when they die. It is harder still to see at man cruel to at dog, without feeling pretty sure that the man is not the better of the two.

From the truck to the keel the Rob Roy had this been thoroughly refreshed and beautified. The perfection of a yacht's beauty is that nothing should be there for only beauty's sake. It is in the observation of this strict rule that the English certainly do excel every other nation; and whether you take a huge steam-engine, a yacht, or at four-in-hand drag, it is almost generally allowed, and is certainly acknowledged by the best connoisseurs of each, that ornament will not make a bad article good; while it is likely to make a good one look bad. Even the flags of a yacht have each a meaning, and are not mere colours. Therefore they ought to be made, at all events, perfectly correct first, and then as pretty and neat as you please. I examined the flags of all the boats and yachts, and steamers at the Exhibition; and there was wonderfully little taste in their display, nearly every one -English and foreign-was cut wrong, or coloured wrong, or too large for the boat that carried them. Even our Admiralty Barge, where specimens of boats from England were exhibited, had a flag flying, with the stripes in the jack quite wrong. She was the only craft on that side of the Pont d'Jena, but as it was the English side (though some English yachts had gone to the other side), I anchored there, right opposite the sloping sward of the Exhibition, and I did this without asking any questions. It is best now and then to do right things at once, and not to delay until time is wasted in proving them to be right

To write after at visit to the Exhibition and not to describe it, will be a double good--to him who writes and those who read of his visit. Of the Paris hotels and lodgings, too, I have no traits to give, because I did not use them, but slept on board my little craft in perfect comfort, and could spend all the rest of the day on shore. Each morning about 7 o'clock you might notice a smart-looking French policeman standing on the grass bank of the Exhibition, and staring hard at the Rob Roy. He had come to see her captain at his somewhat airy toilette, and he was particularly interested, if not amazed, to witness the evolutions of a toothbrush. Perhaps he found them not only interesting but instructive, and involving an idea perfectly new--hard also to comprehend from so distant an inspection. Surely this strange implement must be a novelty imported from England for exhibition here. As he gazed in wonder at the rapid exercise, I sometimes gave the curious instrument an extra flourish above or below, and the intelligent and courteous gendarme never rightly decided whether or not the toothbrush was an essential though inscrutable part of the yacht's sailing gear. Our acquaintance, however, improved, and he kindly took charge of the boat in my absence; not without a mysterious air as he recounted its travels (and a good deal more), to the numerous visitors--many of whom, after his explanations, left the Rob Roy quite delighted that they had seen "the little ship which had sailed from America!"

My Policeman [104]

The boat "Red White and Blue" he thus confounded with mine--was at that time not far off in at house by itself, amid the other wonders which crowded the gardens of the Exhibition. The two venturesome Americans who came to Europe in this ship had but scant pleasure either in their voyage itself or in their visit to France and England. Storm, wet, and hunger on the wide Atlantic were patiently borne in hopes of meeting a warm welcome in old England; but, instead, they had the cold chill of doubt. Much of their sufferings in both these ways were directly due to their own and their friends' mismanagement, the stupid construction of their cabin, the foolish three-masted rig of their boat, the boastful wager of the boat's builder, and their imprudence in painting up the boat on loner arrival, and tarring the ropes; and, lastly, in allowing at mutilated paper to be issued as their "original log."

Disappointed here, they turned to Paris, expecting better days. Fair promises were made-. Steamers were to tow the boat up the Seine in triumph, but it was towed against a bridge and smashed its masts. Agents were to secure goodly numbers to visit her; but for three months scarcely any one paid for a ticket, until at length the vessel was admitted into the grounds of the Exhibition, and there I hope their former losses were made up. Whatever may be thought as to the wisdom or advantage of making such at voyage and in such a boat, it is at very great pity that when it has been effected there should be at failure in appreciating its marvellous accomplishment.

The possibility of taking that boat across the Atlantic, with west wind prevailing and with no rocks or shoals to fear, is altogether beyond doubt. The ill-fate of two other boats that have tried the feat shews how dangerous an experiment it is to try. But after examining, go far as I could (and probably more than anybody else), the evidence in their case -- the men, the log, the documents, and affidavits, and the boat, and its contents, and after hearing, with due attention, the numerous doubts and criticisms from all quarters, both in London and Paris, and in Dover and Margate, I have good reason to believe that the "Red White and Blue" had no extraneous help in her voyage; and, it being certain, that she has come across that wide ocean, therefore, at present I believe she came over unaided; and I only wonder that men able to perform such a deed should be incapable of building and rigging their boat so as to do it comfortably.

CHAPTER VIII.

Presents -- The Emperor -- Anecdote -- The Abbé in London -- A vert -- Singing girl -- English bird -- Model -- Old friend -- The Turks -- Guzzling -- The friture

As they walk past the building where this travelled ship is shewn, many of the visitors seem each to be reading at paper in his hands, while some have a gilt-edged book, and others a broad sheet with a large woodcut on it.

These people have come past that other building, which seems to be all windows; and let us stop there a few minutes to see why the groups crowd round the open windows, and reach out their hands, and go away reading.

If you hear that it is "only some tracts" being given away, and then turn away yourself, you will have lost a wonderful sight: one that, well pondered upon, has wide suggestions to the mind that thinks; and a sight that, of its kind, is quite unexampled at any time and anywhere. Inside this building, and another near it, are hundreds of thousands of Bibles, Testaments, periodicals, papers, picture books and tracts, beautifully printed in the languages of visitors from distant lands, and mostly given free to those who will receive them.

Even in England, at none of our Exhibitions or any other place, has such a proceeding been permitted, doubtless from prudential reasons--the " fear of ''giving offence or exciting disturbance -- so that it has been left to France, with an autocrat ruling an excitable people, and at a time when pleasure seems the chief and only object of all, to brave these supposed dangers, and, despite all scruples, to give utmost freedom to the distribution of God's Word and of man's comments upon it.

The fact is, if you mean to get at all the people, you cannot find them in the same place or reach them by the same road, or treat them in the same way; and all the people must be got at somehow.

As fast as they could hand them out of the rooms, several persons were delivering these books and papers into the open hands of the people, and when a window became vacant, and there was need of some one to help, I took my place there.

We intended to stay only a short time, but six hours passed before the interesting work could be left; and I can never forget those hours, and the subsequent occasions of the same sort.

Every variety of person came quickly before us, of nationality, of manner, of dress, of language, and of bearing, as each drew near, took a paper, read a few lines, thanked the donor, and then went off reading as they walked, or with reflecting gaze, or simply astonished.

Hundreds of soldiers came to the window, sometimes a dozen of them at once, and these all asked for their 'Empereur.' This meant the June number of the well-known periodical 'British Workman,' which was translated into French, and had a very large and well-done woodcut of Napoleon III on its broad first page. The generosity of some good men supplied funds to give one of these Emperor papers to every soldier, policeman, and public employee of every other kind, and much additional interest was attached to the paper because it was actually printed before their eyes at a press in the centre of this building of windows, and because the press itself had borne off a gold medal for excellence of workmanship.* Priests came often.

* The soldiers liked these so much that it was the fashion to place the "Emperor's" picture over each man's bed. On one occasion His Majesty happened to notice this when visiting a guardroom, and he had the whole story explained to him. The Prince Imperial also came for a 'British Workman,' and probably it was pinned behind His Royal Highness' four-poster.

Some of these even returned to get supplies of tracts for their villages in distant parts of France. Germans asked for tracts in "Allemand," and numerous Italians and Spaniards asked for them in their languages. Two Russians came, but we had no books then in Russ; and at length four grave Mussulmen stood before me in turbans and flowing robes, with a suppliant but dignified air, while their interpreter said they wanted to buy a dictionary to learn English from.

Although in frequent tours in foreign lands we had been accustomed to see minglings of the people from many nations, the sight at this window was more varied in the components of the constant flowing stream of human beings for hours and hours than we ever saw before.

Some years ago, travelling in Algeria with an Arab guide, I put up for the night at an old semaphore station, where was a French soldier in charge. It was far from any houses, and on a high hill, and he had a visit only every fortnight from his friends, who brought him provisions on mules' backs. He willingly let me in, and spread a mattress for me on the floor alongside his own. The Arab he kept outside, and the poor fellow had to sleep coiled up on the doorstep.

The Frenchman was courteous and intelligent; but he had only one thing to rend for many weeks, a vapid French novel. He said he would willingly read something better if he had it. At the next French town I searched for some better book, and this caused me to find the agent of the Bible Society, and so a parcel of books, religious and secular, were sent off to the telegraph station ; but the attention once drawn to the French soldiers and their reading, it was impossible not to follow a subject so interesting and important. The regiment quartered in the town had but a few Testaments.* By a little exertion about a hundred copies were obtained and distributed. I saw the men reading these in the streets for hours under the trees, and I sailed in a man-of-war carrying the regiment to Mexico. Perhaps not one in five of them survived that fearful campaign. Priestly opposition to this giving of Testaments resulted ill an appeal to the General in command. He asked the priests if the book was a "bad one," and when it was not possible to say "yes," he gave it free course. Inquiry was excited by this opposition, and 1500 Testaments were received.

* A friend or mine stated that a French gentleman of good education called upon him one day, and happened to look at a French Testament which lay open on the chimney piece. " Tiens!" he said, "paternoster in the Bible?', when he saw the Lord's Prayer in the printed page.

There was a remarkable contrast between the absence of public efforts by French Romanists to disseminate their opinions at the Exhibition and the unusual freedom for others, sanctioned by the present Archbishop of Paris. Various causes were at work to produce this very unexpected state of things, and they will not be alluded to here.

But the points thus noticed remind one forcibly of what actually occurred in 1851, when the Archbishop of Paris specially appointed the Abbé M--, a learned and able man, to go to London and to do his best to further Romanism here during the Exhibition.

One of his first acts was to issue two small tracts on the supremacy of the Pope and of St. Peter; and some hundred thousand of these, beautifully printed, were distributed in London. A copy came to the hands of a clever layman, well skilled in the Popish controversy; and he saw immediately that this little tract, if not well answered, might do much harm.

After careful study of the subject he wrote to the Abbé calling attention to several important misquotations in the tract which were evident when it was compared with original documents in the British Museum. The Abbé replied, that he was not responsible for the accuracy of the extracts, but that they had been given to him by Cardinal Wiseman.

The Protestant layman then wrote a series of letters in an English newspaper upon the subject treated in the tract, and for the time the matter dropped. Years afterwards he received a letter from the Abbé, stating that these newspaper articles had convinced him of the need of inquiry into the subject, and he went to Rome to consult his former instructors. Finally, this Abbé, selected as the champion of Rome by the Archbishop of Paris, and convinced by the arguments adduced by a layman in London, renounced the Romish errors and church, and though offered promotion for his past services, he came to London and went straight to the house of the layman, whom he had not yet seen.

Often have I walked with that clever Abbé riveted by his deeply interesting conversation, his new and fresh views of English life, his forcible exposures of those false estimates of Protestant truth that had for so many years blinded him, and his explanations of the machinery then in action at the Oratory, near the Strand.

But his former allies could not brook the desertion of so formidable a champion, and lie was driven by their continual annoyance to seek another home. So he went to Ireland, and soon became the best teacher of the French language in Dublin, from whence he removed to America. Let us hope that there, at least he is free to profess the truth he had found, and to be one of the instances-very rare indeed they are-of a consistent and steady Protestant, who had for years before been thoroughly imbued with those doctrines which gnaw at the very vitals of mental perception, and obliterate the sense of fairness, and very seldom leave enough alive in the mind to hold even real truth firmly.

It will not be breaking the promise that our visit to the Exhibition is not to involve us in a description of all its wonders, if we walk upstairs and look into the Tunisian Café, attracted by the well-known drumming and the moaning dirge which Easterns call music. Tunis is best seen out of Tunis, for the embroidered gold and bright coloured slippers can then be enjoyed without those horrible scenes of filth-dead camels, open sewers, and maimed beggars which encase the shabby mud walls so near the marble ruins of old Carthage.

The café was full of visitors. English and Americans were admiring a pretty singing girl about fifteen years of age, who was beautifully dressed, and sitting with four very demure and ugly Oriental in the little orchestra.

Soon she rose and sang a song. Black eyes, blackest of hair, pale cheeks, languid grace. She is a fair daughter from the rising sun. " Yes, there is certainly a something in their Eastern beauty which is quite beyond what Britons or Yankees see at home."

But the words and music of the song seemed known to me. Surely she is now singing English while she shakes the golden sequins in her long jet hair and rattles her tambourine. We asked a waiter, and he said she could sing Turkish, Spanish, French, and English. At last being persuaded that her pronunciation of English was too distinct for a foreigner, we took the very bold measure of going up to the orchestra, and saying to the young lady, "You are English, are you not?" She stared, and held down her face, which still was pale, even if she blushed, and answered, "Yes, sir." "Are you here alone ?-no relation, no woman friend with you ?" "Yes." "And do they treat you well?" "Yes." "From what part of England?" "From --shire." I said she seemed to mean the words of the song she had sung, 'I wish I were a bird, and I would flee away,'

And asked if she could read, and would like a nice book. "Oh yes, I should, and very much." Now there was a stall set up in the Exhibition by the Pure Literature Society, from Buckingham Street, Adelphi, London, which selects about three thousand books from various publishers, but publishes none itself; so that its catalogue is likely to contain rather what it may wish should be read than what it may hope will be bought.* Here we selected a very interesting volume with many illustrations, suitable for the girl's reading; and soon at the café again, I bowed to the senior fiddler, who nodded assent, and then the poor pale lonely girl had the pleasant book as a remembrance of home placed in her hands, and a promise given her that a good Christian lady would call that evening.

So perhaps our catalogue of nationalities at the Exhibition ought to be somewhat abridged, and not wholly founded upon the variety it presents to the eye; especially as in London, too, we may remember Punch's crossing-sweeper, who, being dressed in Hindoo garb, begged from a passerby with, "Take pity on the poor Irishman -- Injun, I mane."

Among the curiosities exhibited in the English naval architecture building here was a very beautiful model of the Rob Roy canoe, presented to its owner by the builders, Messrs. Searle, who have already built about ninety such canoes on the principles first applied in that above mentioned; and to me it was even more gratifying to find in the Admiralty Barge, the Rob Roy canoe itself, with sails set and the flag of the Canoe Club flying, and with maps of the paddling voyages through Europe.

*A similar Society has begun operations in France by publishing translations of English papers on Sanitary and Domestic Management.

Very speedily I launched my old travelling companion, and had a paddle up the river by moonlight, and it was surprising to find that scarcely any water leaked in, though the other boats which were hung up, or on the deck, or swung from the davits of the barge, were found to be a good deal injured by the strong draught of wind rushing through the arch of the bridge, and then under the open sides of the shed, covered only by a roof. Bat then those other boats were new, and perhaps some were not built of such well-seasoned wood * as Messrs. Searle employ beyond all other boat-builders I know; whereas the weather-beaten Rob Roy had been too long inured to wet and dry, sun and wind, heat and cold, to be affected with the rheumatism and ague which shook even the man-of-war's boats on the barge.

*In this one particular the canoeist has to trust to the boatbuilder. In others, and in those relating to the rigging and sails especially, I regret to say that I do not find any builder fulfil those requirements of strength, lightness, neatness, and simplicity combined in due proportions, upon which so much of the safety of a canoe depends, as well as comfort and pleasure in using it during the many days' constant 'work of a long voyage. The proper rigging of a canoes, so as to be neither fragile likes a toy nor clumsy in its small details, is now better attended to by Mr. Lawrence at the Model Dockyard in Fleet Street.

On the Sunday the little dingey had its usual cargo, and the bargemen on the Seine, in the heart of Paris, were just as glad as others elsewhere to get something to read. But it is time to end this narration of the same sort of incidents repeated so often, though each was interesting as it occurred. So I may close by the sketch below, which represents a man watering a horse, and who swum it out to my boat to get a paper, and then carefully placed the gift in a dry place ashore until he should be able to use it when he was dressed again.

Sunday Ride[118]

The life at the Exhibition soon settled into a somewhat regular one with me. Seeing, seeing all day, and then returning to my quiet bed on the river at night, with a 'Times' newspaper to study, and books and letters. It was a variety to loosen the dingey, and scull along the quays and visit the other yachts, all of them most hospitable to the Rob Roy. I ventured even to go alongside the Turkish vessel, the Dahabeeh, from the Nile, full of specimen "fellahs," all hidden by a curtain of grey calico, except to those who had paid their franc for general entrance. We never observed any visitor actually on board this vessel; indeed, it required a bold inquirer to face those solemn Africans' gaze, as they sat cross-legged on deck, and ate their soup from a universal bowl, or calmly inspired from their chibouques, and blew out a formal and composed puff of the bluest tobacco-smoke. It did, indeed, soon forcibly recall the feelings of Egyptian travel to see these men ; - the red fiery sunsets, the palms, and crocodiles, and tombs, and Indian corn, and, over all, the thrumming, not unmusical sound of the tarabookrah -- earthen drum -- with the wailing melodies in a minor key of the "Chaldeans whose cry is in their ships."

So I ventured near in my dingey, and the imperturbable Egyptians were fairly taken by surprise. They soon rallied to a word or two in their language and an Englishman's smile, and rapidly we became friends, and talked of Damascus and Constantinople, and finally decided that "Englishman bono!" The shape and minute dimensions of my dingey much astonished them; but they believed, no doubt that in that very craft I had come all the way from London.

The luxury of Paris must have at least some effect in making gourmand's of the young generation, even if their fathers did not set the example. The operation, or rather the solemn function, of breakfast or dinner, is with many Frenchmen the only serious act in life. Where people can afford to order a dinner in exact accordance with the lofty standard of excellence meant by its being "good," the diner approaches the great proceeding with a staid and watchful air, and we may well leave him now he is involved in such important service. But with the octroi duty for even a single pheasant at two shillings and sixpence, there are many good feeders who cannot afford to "dine well," and the fuss they make about their eatables is something preposterous. It is a vice -this gluttony-that seems to be steadily increasing in France for the last twenty years, at least in its public manifestation, and moreover it is an evil somewhat contagious.

One evening, while some of us had dinner at the Terrasse in St. Cloud, a family entered the room, and were partly disrobing themselves of bonnets and hats for a regular downright dinner, when the waiter came, and in reply to the order of a "friture," he calmly said they had none.

At this awful news the whole party were struck dumb and pale, and leant back on chairs as if in swoons. The poor waiter prudently retreated for reinforcements, and the landlady herself came in to face the infuriate guests.

"No friture !" said the father. "No friture, and we come to St. Cloud?" He muttered deeply in rage. His wife proceeded to make horribly wry faces whereat Rob Roy irreverently laughed, but he was not observed, nothing indeed was noticed of the external trifling world). The daughters heaved deep sighs, and then burst into voluble and loud denunciations. Then the son (who wanted dinner at any rate, and the objurgations might do afterwards) proposed at once to leave the desolate, famine-stricken spot.

But though this was debated warmly, it was not carried. They had already anchored, as it were, and they resolved to dine starving, and to grumble all the time. For all the time of dinner no one subject was talked about except the friture. It was a miserable spectacle to witness, but confirming the proposition, not at all new, that the French care far more about eating than does John Bull.

© 2000 Craig O'Donnell

May not be reproduced without my permission.

Long Reach

Long Reach